OpenSSL example from previous lecture, finished #

cbc_encrypt.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <openssl/evp.h>

#define BLK_LEN 16

#define BUF_LEN 512

// NOTE!! For clarity's sake, this example has no error checking.

// In real code you need to test for errors and handle them.

int main(int argc, const char* argv[]) {

int len, bytes_read;

char passphrase[256];

unsigned char key[32]; // Receive SHA-2-256 hash of user pass phrase

unsigned char iv[BLK_LEN];

unsigned char in_buf[BUF_LEN];

unsigned char out_buf[BUF_LEN+BLK_LEN];

EVP_MD_CTX *mdctx;

if (argc != 3) {

printf("Error: Need two arguments, src and dst files\n");

return EXIT_FAILURE;

}

// Open files to read and write

FILE *src = fopen(argv[1], "r");

FILE *dst = fopen(argv[2], "w");

if (src==NULL || dst==NULL) {

printf("Error: could not open file(s)\n");

return EXIT_FAILURE;

}

// Get passphrase for encryption

printf("Enter passphrase up to 255 characters: ");

fgets(passphrase, 256, stdin);

// Hash passphrase, put 256 bit result in "key"

mdctx = EVP_MD_CTX_create();

EVP_DigestInit_ex(mdctx, EVP_sha256(), NULL);

EVP_DigestUpdate(mdctx, passphrase, strlen(passphrase));

EVP_DigestFinal_ex(mdctx, key, NULL);

EVP_MD_CTX_destroy(mdctx);

// Write a random IV to dst

FILE *rand = fopen("/dev/urandom", "r");

fread(iv, 1, BLK_LEN, rand);

fwrite(iv, 1, BLK_LEN, dst);

fclose(rand);

// Set up context with alg, key and iv

EVP_CIPHER_CTX *ctx = EVP_CIPHER_CTX_new();

EVP_EncryptInit_ex(ctx, EVP_aes_256_cbc(), NULL, key, iv);

bytes_read = fread(in_buf, 1, BUF_LEN, src);

while (bytes_read > 0) {

EVP_EncryptUpdate(ctx, out_buf, &len, in_buf, bytes_read);

fwrite(out_buf, 1, len, dst);

bytes_read = fread(in_buf, 1, BUF_LEN, src);

}

EVP_EncryptFinal_ex(ctx, out_buf, &len);

fwrite(out_buf, 1, len, dst);

// Free memory, zero sensitive stack elements

EVP_CIPHER_CTX_free(ctx);

OPENSSL_cleanse(key, sizeof(key));

OPENSSL_cleanse(in_buf, sizeof(in_buf));

OPENSSL_cleanse(passphrase, sizeof(passphrase));

fclose(src);

fclose(dst);

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

keycomes from a hashivcome from/dev/urandom.

Hashing #

File: Hash notes

Hash functions are algorithms that map a large domain into a small codomain. Cryptographers can use hash functions to authenticate their messages. The message is hashed to a smaller piece of data, and that is used to authenticate the original data.

In order for it to be secure, adversaries should not be able to create the hashes themselves, without having the original data.

There are 2 kinds of hash in cryptography:

Cryptographic hash

- Algorithms like

- MD5 (now deprecated)

- SHA (the standard, “secure hash algorithm”)

- slower

- no one can find two inputs that map to the same output

- no key

Universal hash

- faster

- randomized (does have a key)

- weaker guarantees

Universal hash example – Polynomial evaluation hash #

Note: These polynomials are not related to Galois fields

Let \( p \) be prime.

Good prime numbers to use are something like

- \(2^{127} - 2 \), a Mersenne prime

- \(2^{130} + 5 \), the prime used in POLY1305

Init: choose \( k \in Z_p \) at random.

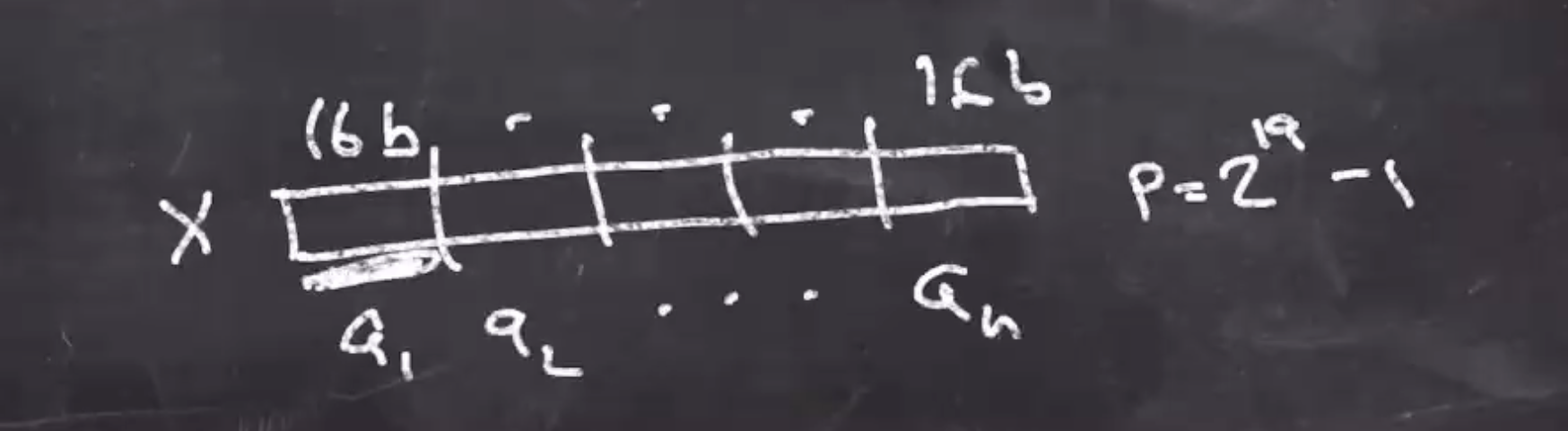

When we hash something, we require to be given a vector of values \( (a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_n) \) each in \( Z_p \) .

The hash value is defined as

\[ (a_1k^n + a_2k^{n-1} + \cdots + a_nk^1) \mod p\]Concrete polynomial hash evaluation example #

- Our prime number will be \( 2^{19} - 1 \)

- Pick \( k \) at random to be \( 1234 \)

The data we want to hash is

0001 0203 0405

chunked into 16 bit quantities. We can think of these as integers

1 515 1029

Our hash result is going to be

\[\begin{aligned} \text{hash} &= \left( (1)(1234)^3 + (515)(1234)^2 + (1029)(1234)^1 \right) \mod 2^{19} - 1\\ \end{aligned}\]A theorem about polynomial hashing #

Theorem: Let \(p\) be prime, and \((a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_n) \neq (a’_1, a’_2, \ldots, a’_n)\) with each \(a_i\) and \(a’_i \in Z_p\).

Then,

\[P(a_1 k^n + a_2 k^{n-1} + \cdots + a_n k^1 \mod p = a’_1 k^n + a’_2 k^{n-2} + \cdots + a’_n k^1 \mod p) \\ \leq \frac{n}{p} \]

The probability that those 2 vectors are equal is very small if \(n\) is small and \(p\) is large.

This theorem is fairly easy to prove.

If we define the hashes to be

- \( \text{hash1} = a_1 k^n + a_2 k^{n-1} + \cdots + a_n k^1 \mod p \)

- \( \text{hash2} = a'_1 k^n + a'_2 k^{n-2} + \cdots + a'_n k^1 \mod p \)

Where

- \( n \) is the number of possible zeros (solutions)

- and \( p \) is the number of candidates for \( k \)

Note: A polynomial in a field \(Z_p\) has the same fundamentals as normal.

Horner’s rule – faster polynomial evaluation #

Horner’s rule is an algorithm for computing polynomial evaluations.

We’ll start with the identity 0, and start by adding it to our coefficient and multiply by our key

\[\begin{aligned} (0 + a_1) k \end{aligned}\]which evaluates to \( a_1 k \)

We then repeat

\[\begin{aligned} ((0 + a_1) k + a_2) k \end{aligned}\]which evaluates to \( a_1k^2 + a_2 k \)

This continues

\[\begin{aligned} (((0 + a_1) k + a_2) k + a_3) k \end{aligned}\]So as long as we have terms to process, we just

- add the coefficient

- multiply by \( k \)

This is good for streaming data!

Here is Horner’s rule as pseudo code

acc = 0

for i from 1 to n

acc = acc + a[i]

acc = (acc * k) mod p

return acc

Divisionless mod #

The most expensive instruction in a CPU is division, so our mod in Horner’s rule can be improved.

If we are calculating

\[\begin{aligned} x \mod y \end{aligned}\]Instead of solving that directly, we’ll look at \( y \) as

\[\begin{aligned} x \mod (2^a - b) \end{aligned}\]Note: Any number can be written as a power of 2 minus a constant.

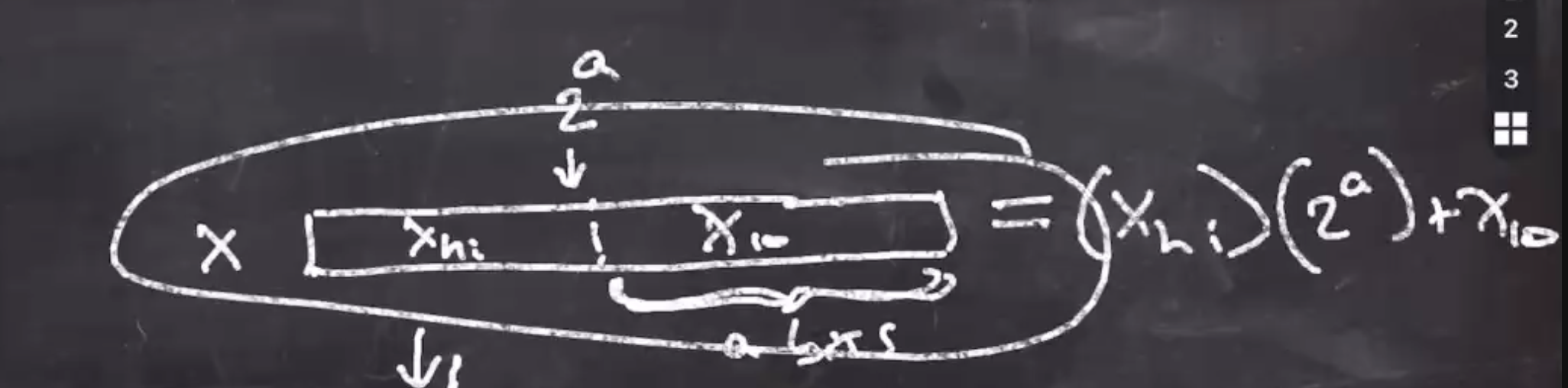

Lets break \( x \) into 2 parts, high and low bits.

The low part \( x_\text{lo} \) will be \( a \) bits long.

If we want to think of decimal numbers:

\[\begin{aligned} 12345 &= 12(x) + 345 \\ &= 12(10^3) + 345 \\ &= 12345 \end{aligned}\]So lets do the same thing but with bits

So we can rewrite our original

\[\begin{aligned} x \mod y &= (x_\text{hi}) (2^a) + x_\text{lo} \mod 2^a - b \end{aligned}\]Note that

\[\begin{aligned} 2^a \mod (2^a - b) = b \end{aligned}\]And we can mod at any time, so lets mod the \( 2^a \) .

So

\[\begin{aligned} x \mod y &= (x_\text{hi}) (b) + x_\text{lo} \end{aligned}\]We can defer the mod to the last step in order to speed up our previous algorithm. So to better our acc pseudo earlier, we can do a divisionless mod.

acc = 0

for i from 1 to n

acc = acc + a[i]

acc = acc * k

divisionless mod

return acc mod p

For example,

If we want to calculate

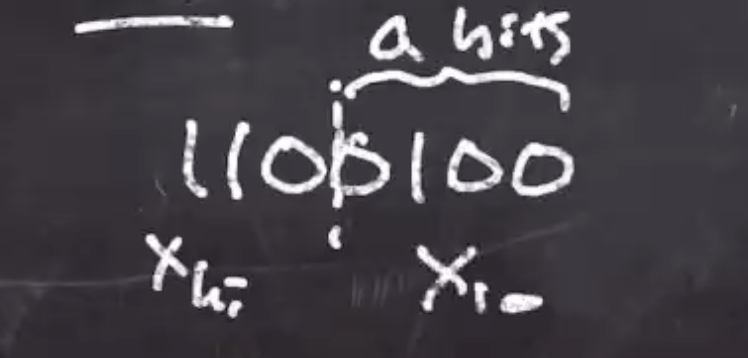

\[\begin{aligned} 100 \mod 14 \end{aligned}\]So \( 14 = 2^4 - 2 \)

We can break the binary up to the bottom \( a \) bits,

Note that 16 is greater than 2 (the actual answer), but this intermediate result is congruent. So a final mod at the very end of the algorithm is needed to get the actual result.

File: Hash tricks pdf