Introduction to push-down automata #

A push-down automata is a finite automata with memory, more than what state its currently in. It is a non-deterministic finite automata with a stack for memory. Since it is drawn very similarly to drawing finite automata, we will just notate how the stack is being manipulated on the transitions.

Drawing transitions for PDAs #

Each arrow has a triple: a,b,c, where

ais the char to consume from input (or \( \lambda \) )bis the char to pop from the top of the stack,bis always popped when following this transitioncis a string to push onto the stack (from right to left)

An arrow can be followed if and only if:

amatches next input char (or \( \lambda \) ), andbmatches top of the stack

Following the arrow: consumes a, pops b, pushes c

Convention: when drawing the PDAs, \( \emptyset \) signifies the bottom of the stack at start.

Steps to follow when creating a PDA #

- Think of a stack-based algorithm

- Try to implement the algorithm with a PDA

Example 1 #

The language \( L = \{a^n b^n: n \geq 0\} \) represents the strings \( \{\lambda, ab, aabb, aaabbb, \ldots\} \) .

We saw earlier that we cannot represent this language using finite automata, proving it wasn’t a regular language. Let’s think of an algorithm to accomplish this language:

- Consume an \( a \) and push it onto the stack

- When we start to see \( b \) ’s we pop an \( a \)

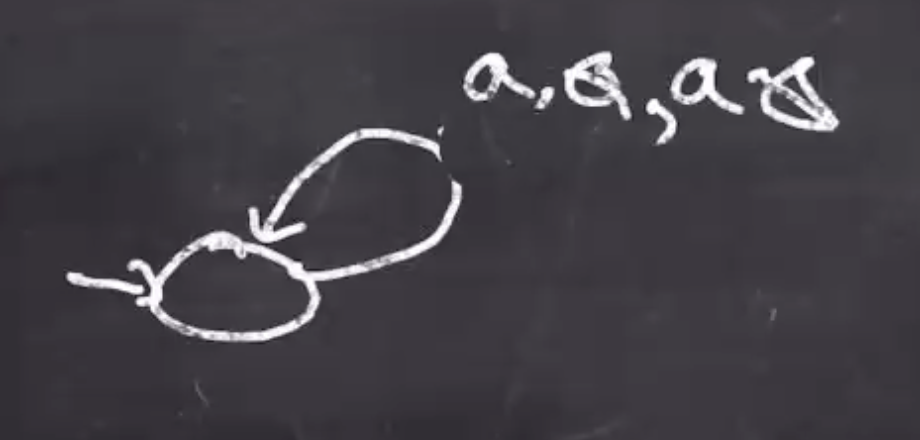

We can start with the first \( a \) seen:

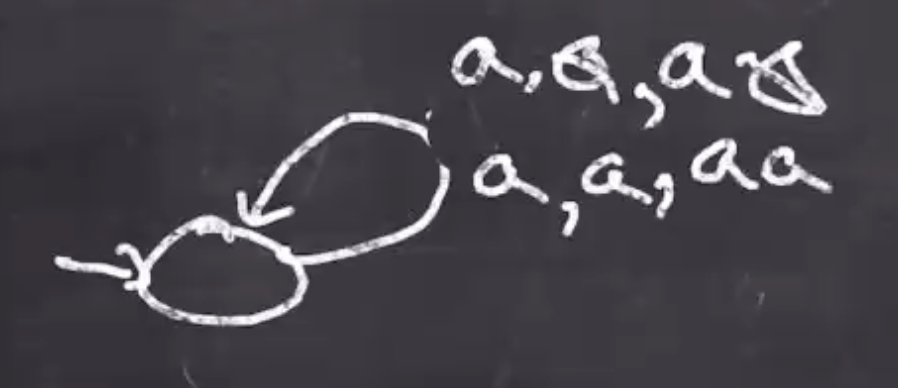

Then we can self loop for the next \( a \) when there is already one on the stack:

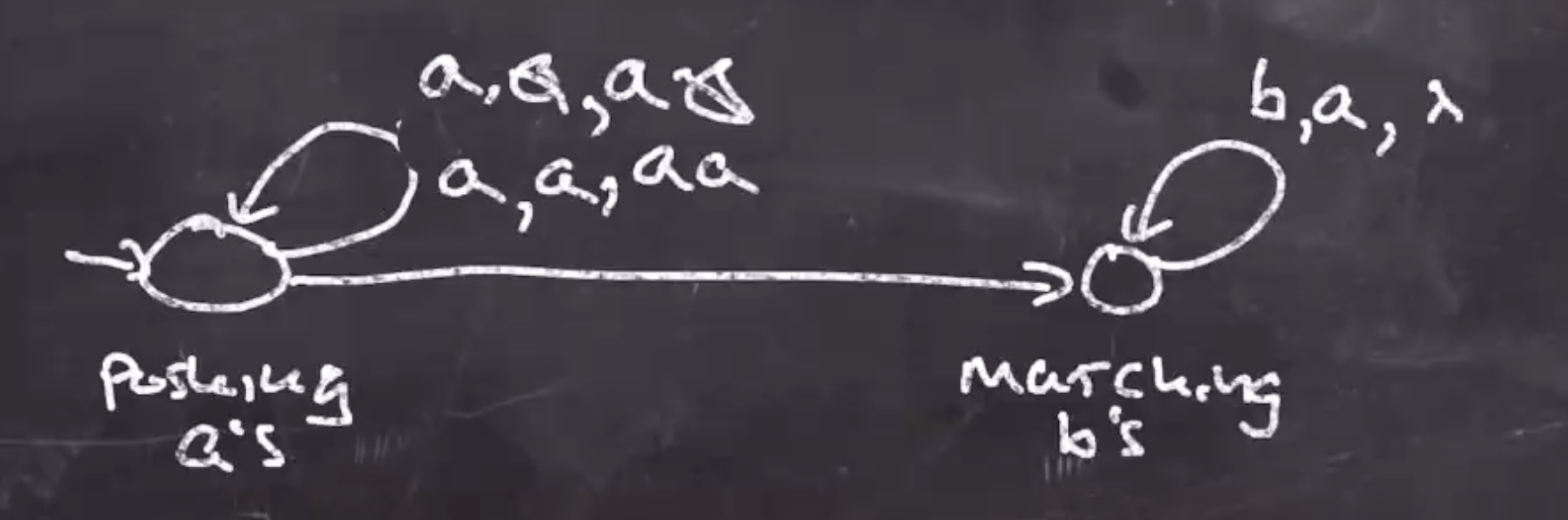

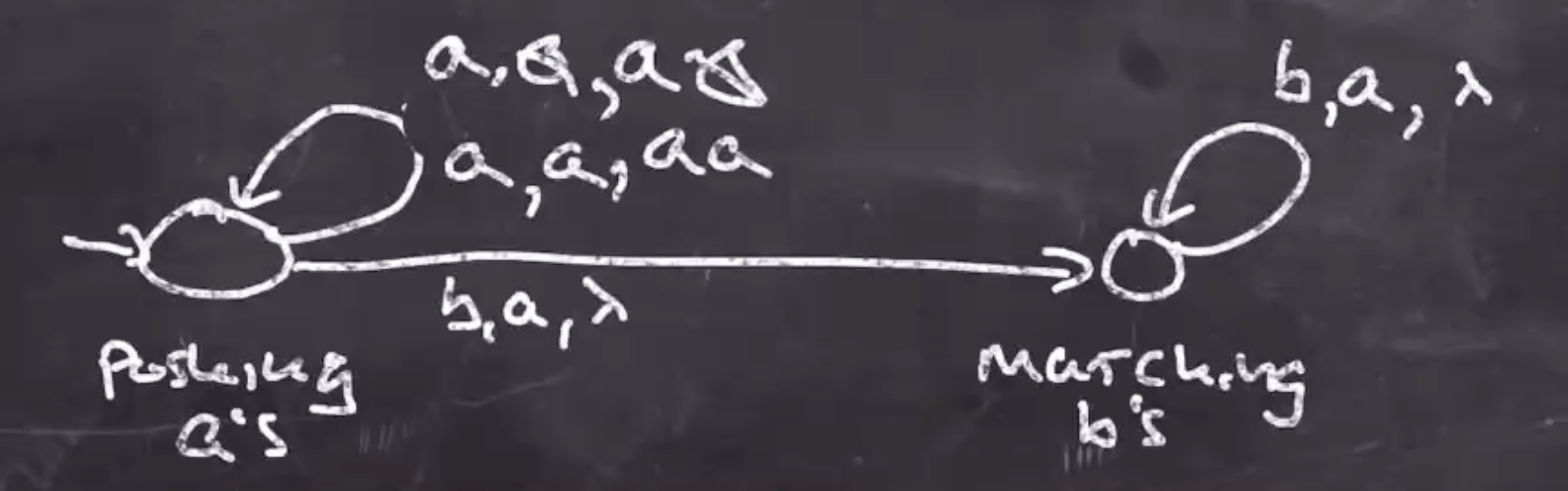

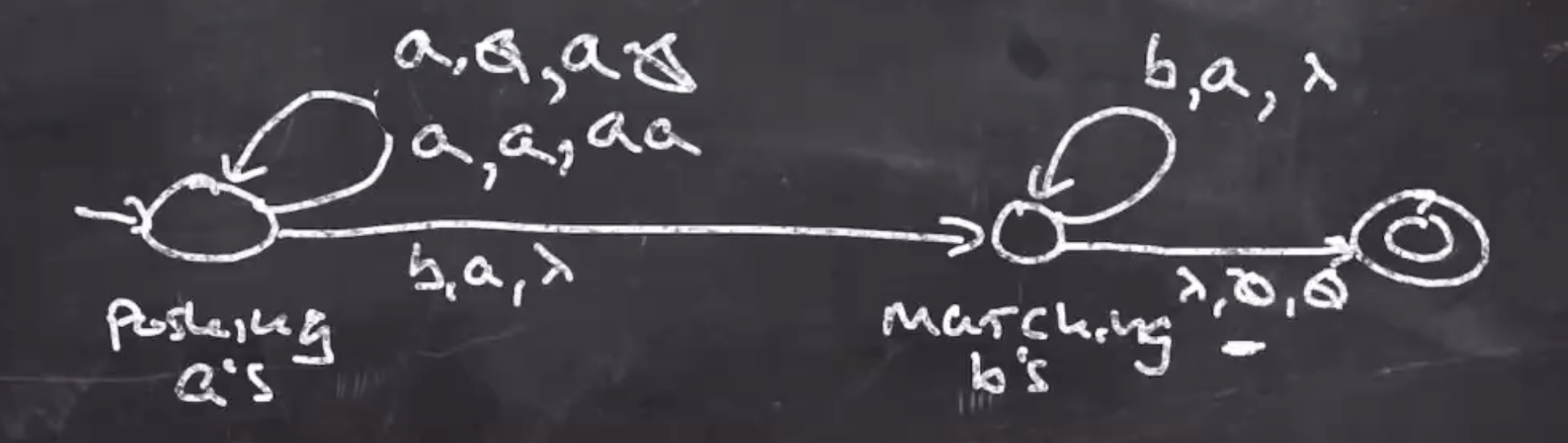

We can think of the first state as “pushing \( a \) ’s onto the stack.” After this phase we will move onto “matching \( b \) ’s”, this will be our second state.

The first self loop consumes the \( b \) , and pops the \( a \) , and pushes the empty string back to the stack ( \( \lambda \) ).

The arrow transitioning from the first to the second state will be \( b,a,\lambda \) :

Note: This arrow could also be labeled \( \lambda,a,a \)

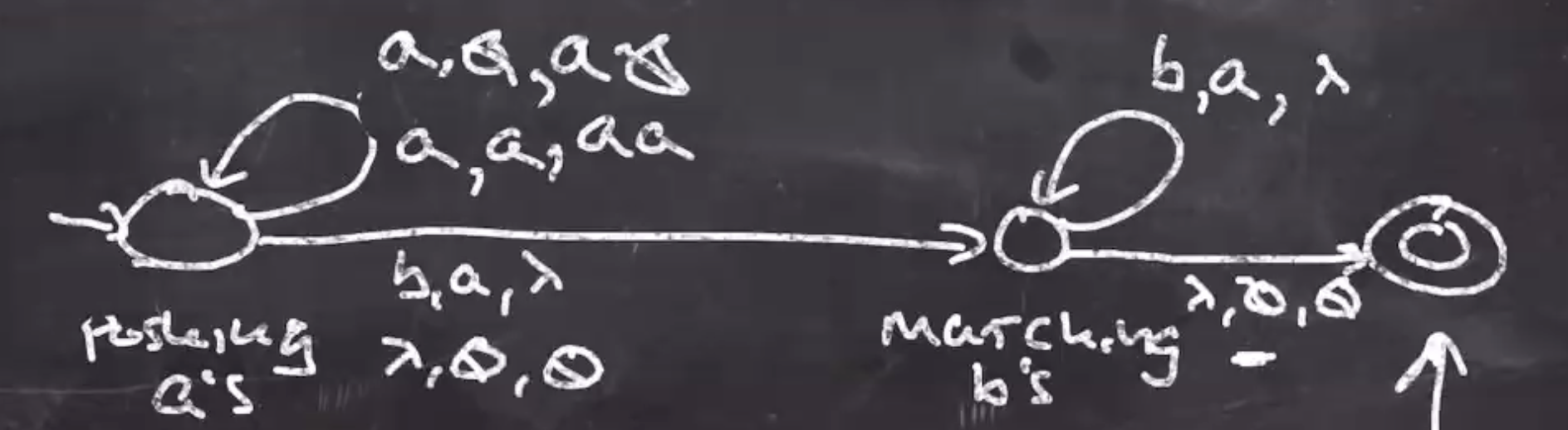

At this point the PDA will work with all of the good strings in the language. To decide where the accept state is we need to think of what the stack should look like once the string is consumed. When we no input and the bottom of the stack, we can accept, \( \lambda, \emptyset, \emptyset \) :

String is accepted if and only if \( a^n b^n \) seen and all input is consumed. The last thing to take care of is accepting the empty string \( \lambda \) . To do this, we can add \( \lambda, \emptyset, \emptyset \) on the middle arrow:

Example 2 #

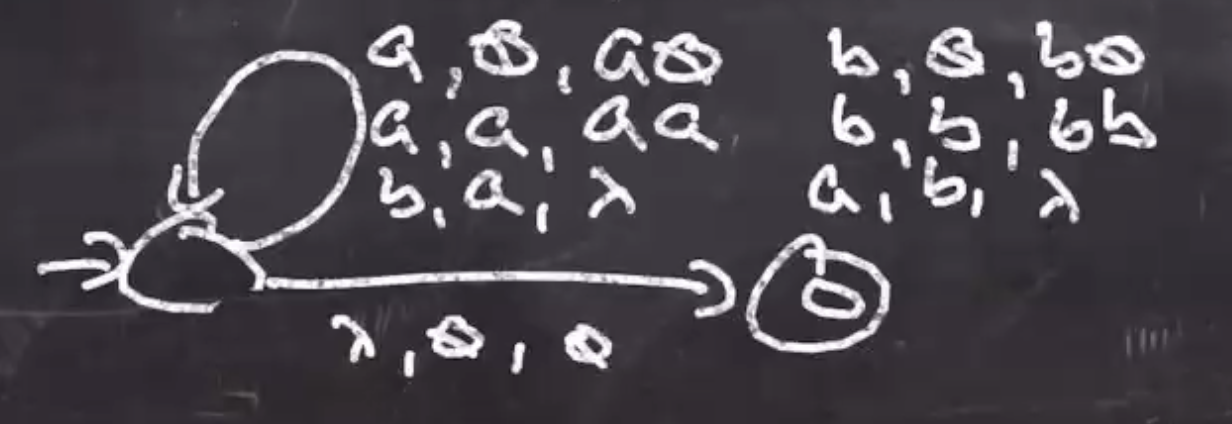

Consider the language \( L= \{w \mid w \in \{a,b\} \text{ and } w \text{ has equal number of } a \text{'s and } b \text{'s} \} \) .

To accomplish:

- Use the stack to keep match of excess

Input is accepted if and only if all input is consumed with an equal amount of \( a \) ’s and \( b \) ’s (stack is empty).

Relative power of PDA #

Recall, we showed that any NFA can be expressed as a DFA, therefore they have the same expressive power. Every NFA can be turned into an equivalent PDA.

Any arrow labeled \( x \) in a NFA can be expressed as an arrow triple \( x, \emptyset, \emptyset \) in a PDA.

Therefore, the power a PDA has is greater than or equal to an NFA’s power.

PDA’s can recognize \( a^nb^n \) , and no NFA can recognize this language.

So a PDA is not equal in power to a NFA, so therefore it must mean that a PDA is greater than a NFA in expressive ability.