Common divide and conquer problems #

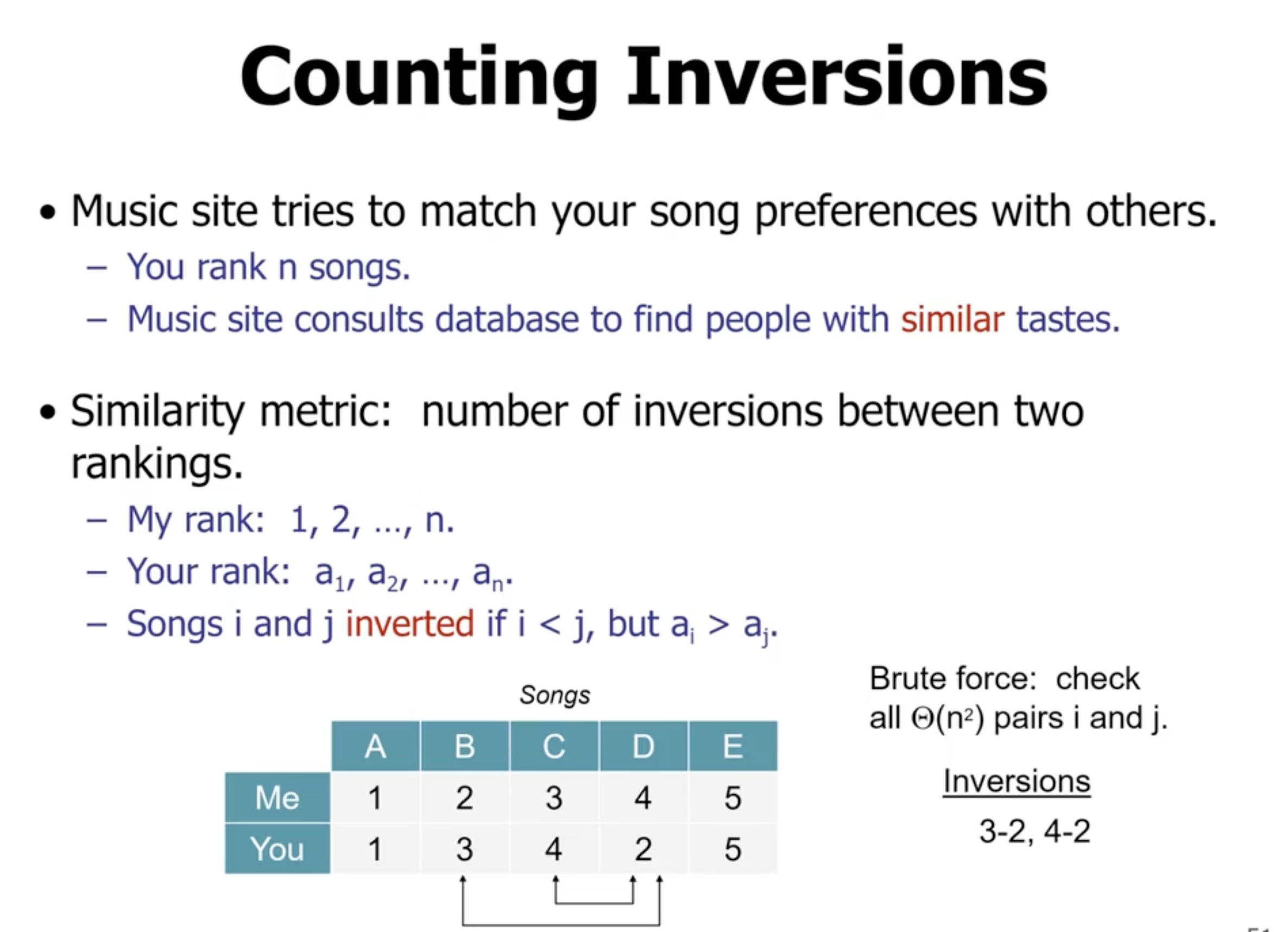

Counting Inversions #

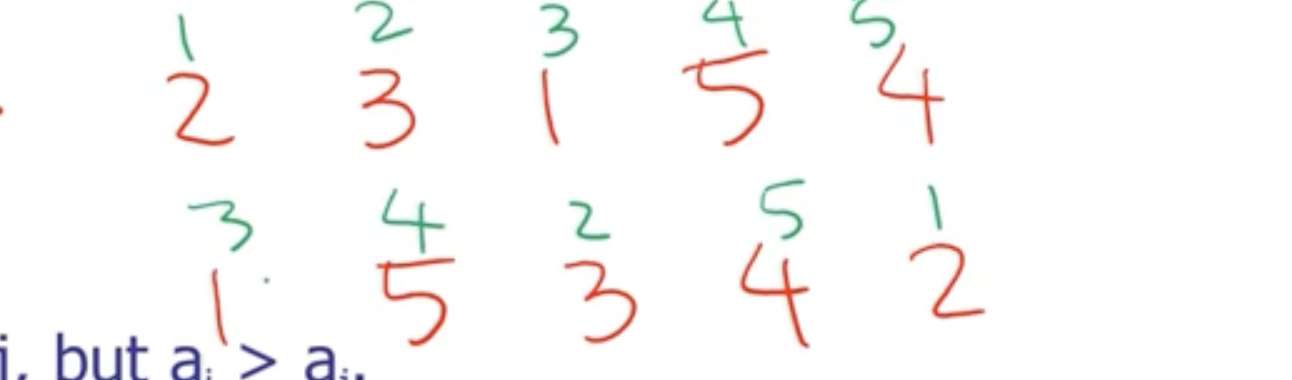

Inversions are the number of out of order pairs in an array of numbers. We can use the amount of inversions as a ranking for multiple arrays.

If we consider the first array as sorted (the indices), we can use the second array’s indices as a rank to compare.

When we try and count inversions, we are given an array of \( n \) numbers.

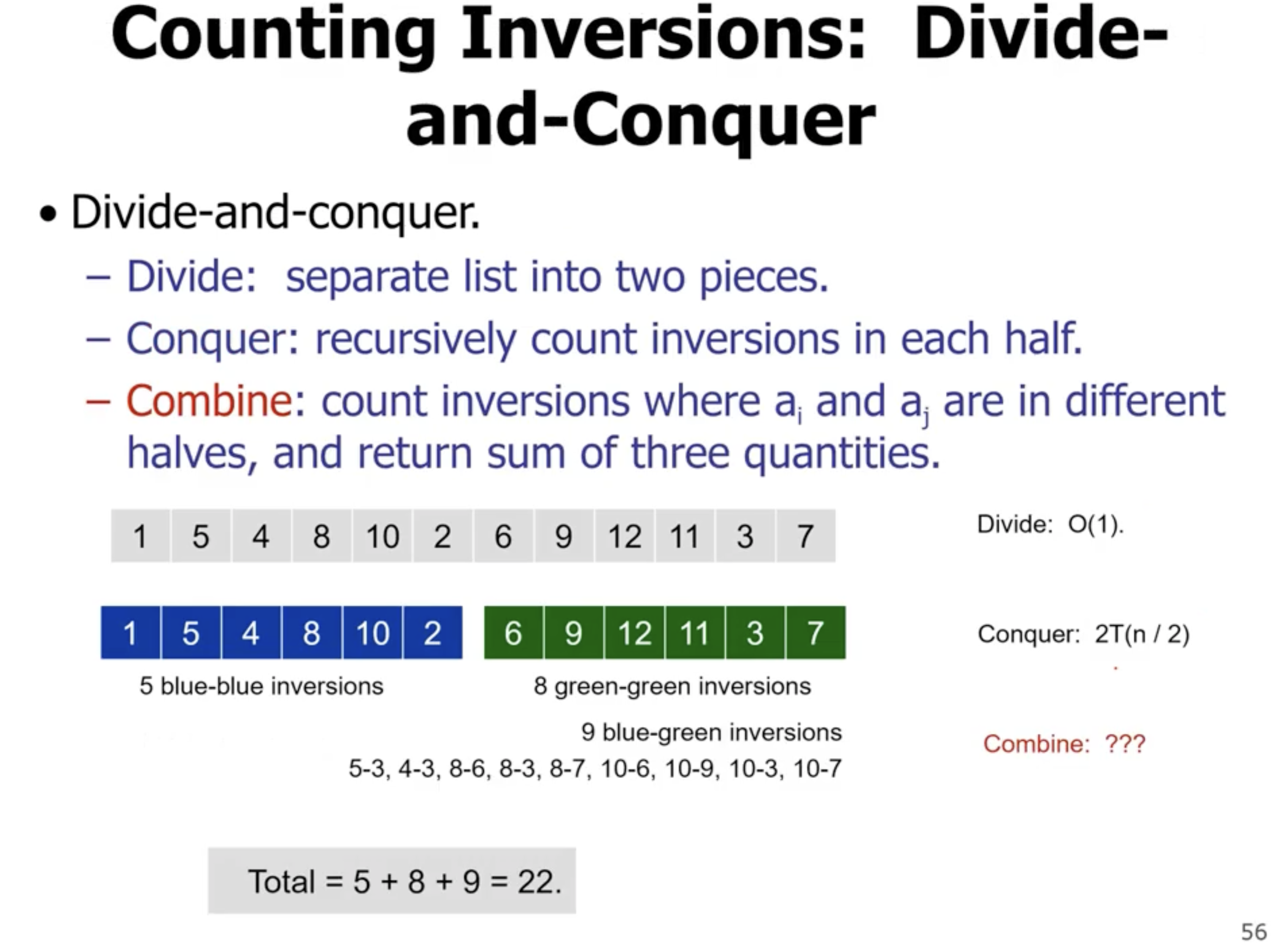

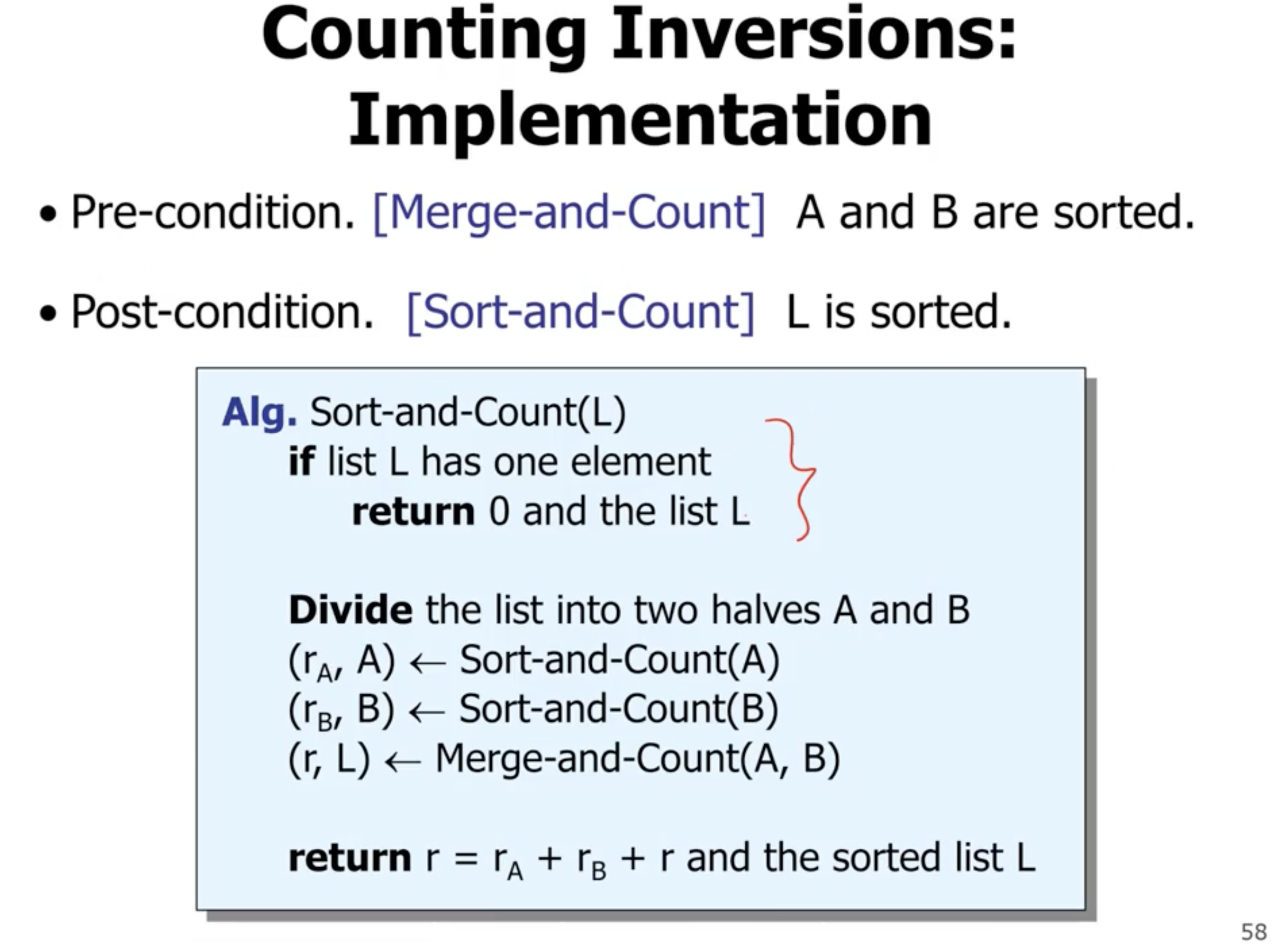

We can use divide and conquer to count the number of inversions.

- split the array into 2 subarrays

- count the inversions in each subarray

- combine the answer

The problem with the combination step is that we have to count the number of inversions between the 2 subarrays now. So after each subarray is counted, we can loop over the first array and compare to each element of the second array. We can’t really do better than this. This means the combination step is \( \Theta(n^2) \) .

\[\begin{aligned} T(n) &= 2T \left( \frac{n}{2} \right) + \Theta(n^2) \\ &= \Theta(n^2) \end{aligned}\]This is no different than just looping over the entire original array and comparing the numbers.

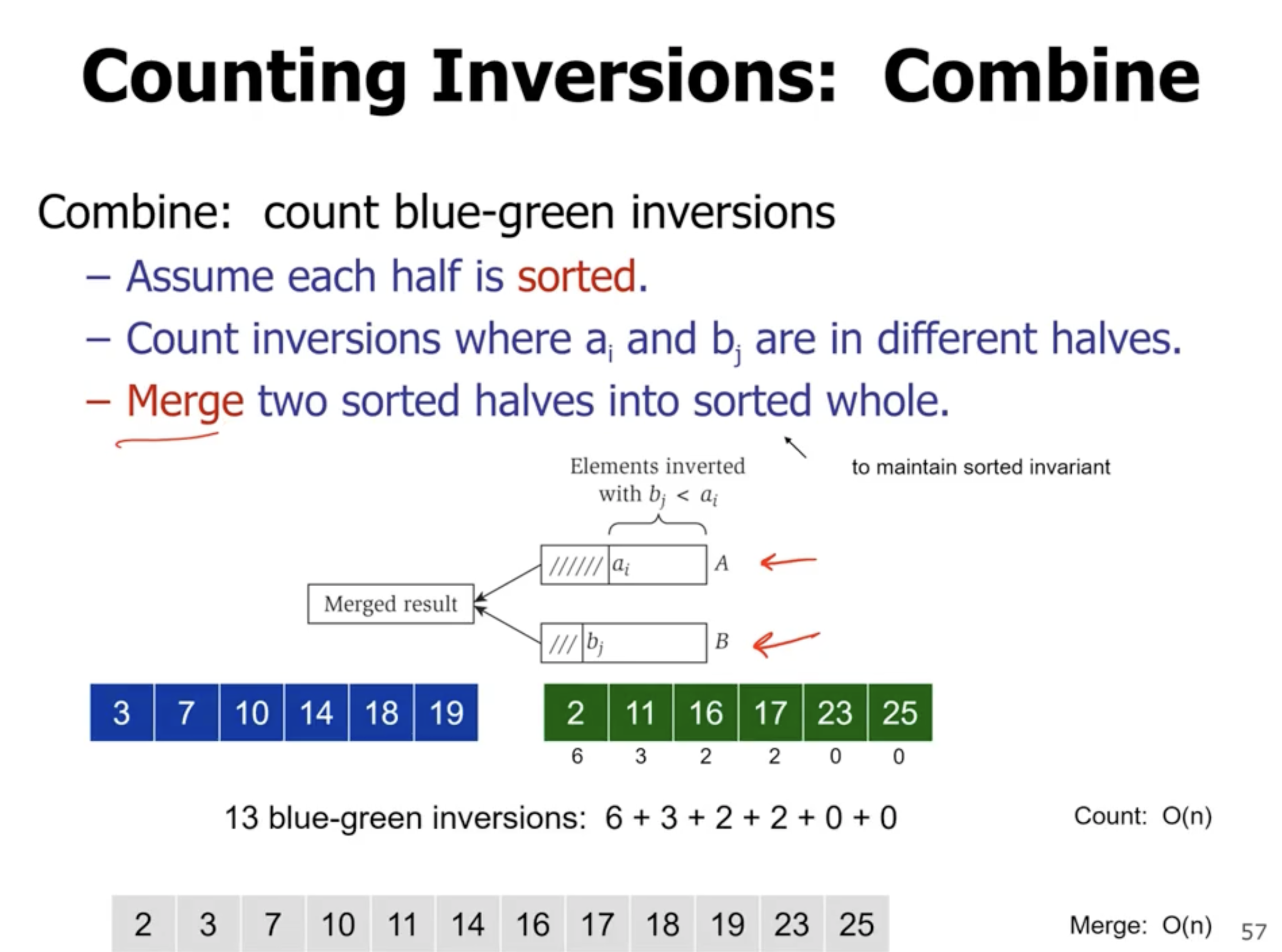

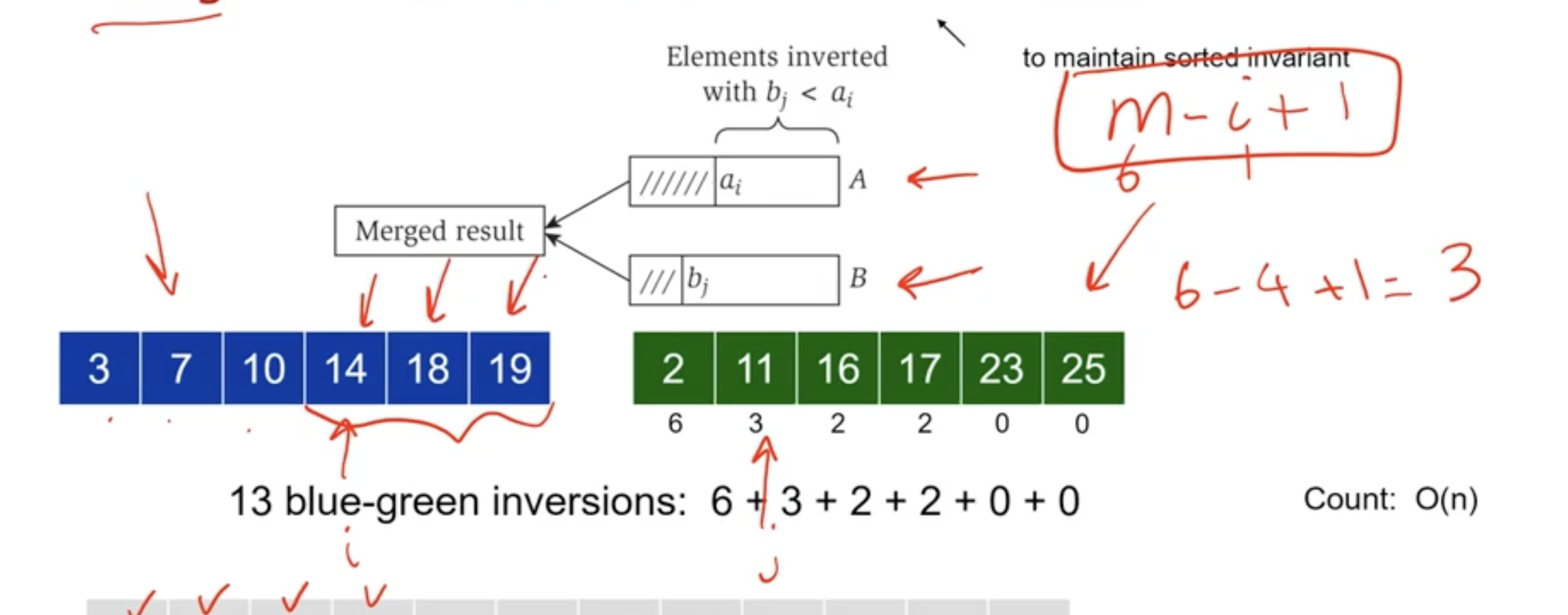

So how can we do better? If we are never working with sorted arrays, we cannot do better. However, if we sort the array before we return the subarray result, we can do better.

While we are mering the 2 subarrays, we can count the inversions. If the smaller value is coming from the second subarray, then we have an inversion. If we have \( m \) items in a subarray, and \( i \) points to the item in the first subarray, then we have \( m-i+1 \) inversions for the item in the second subarray.

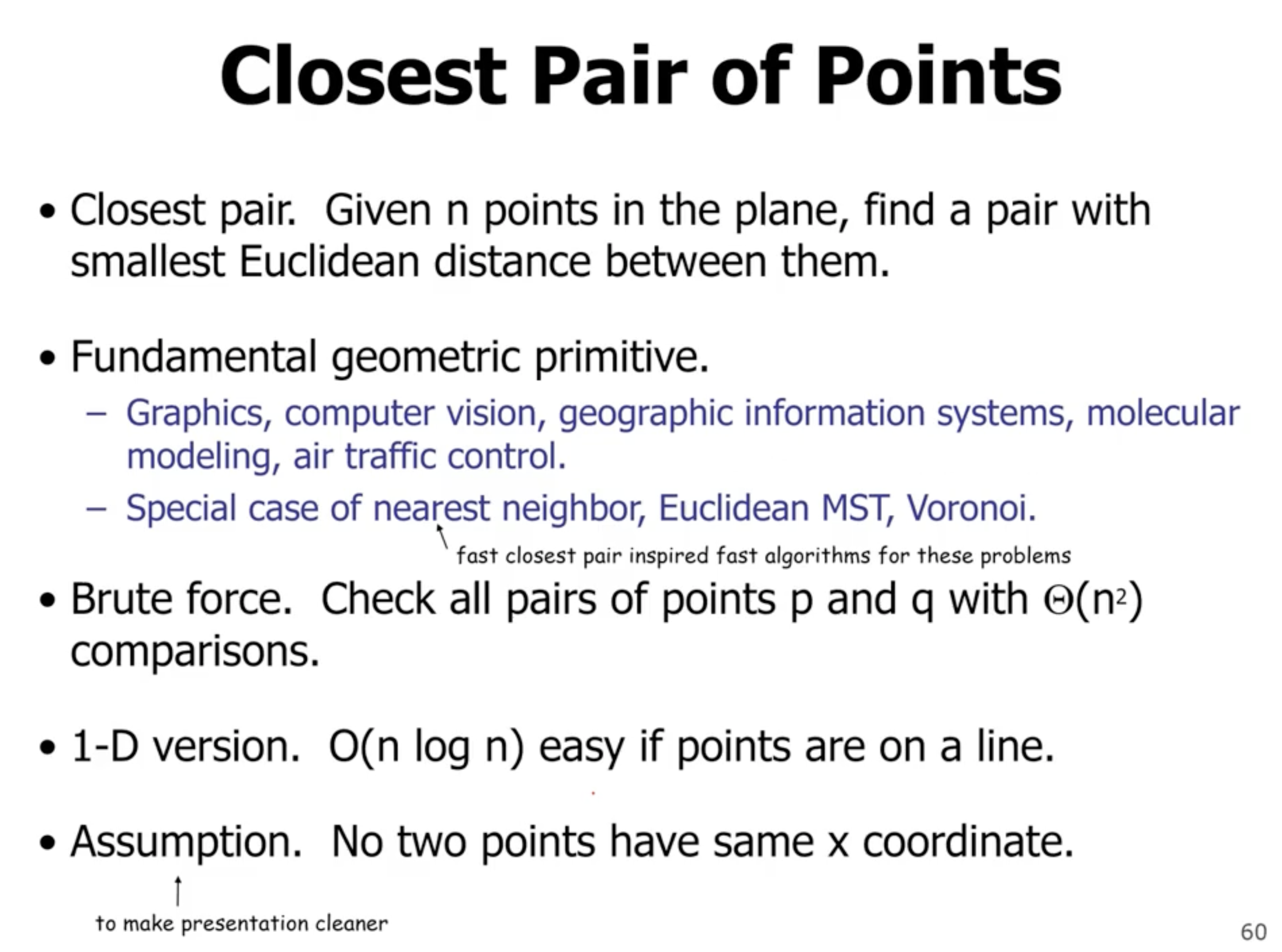

Closest pair of points #

If we are working with a 1D array, we can sort them and then loop thru once and find the adjacent pairs.

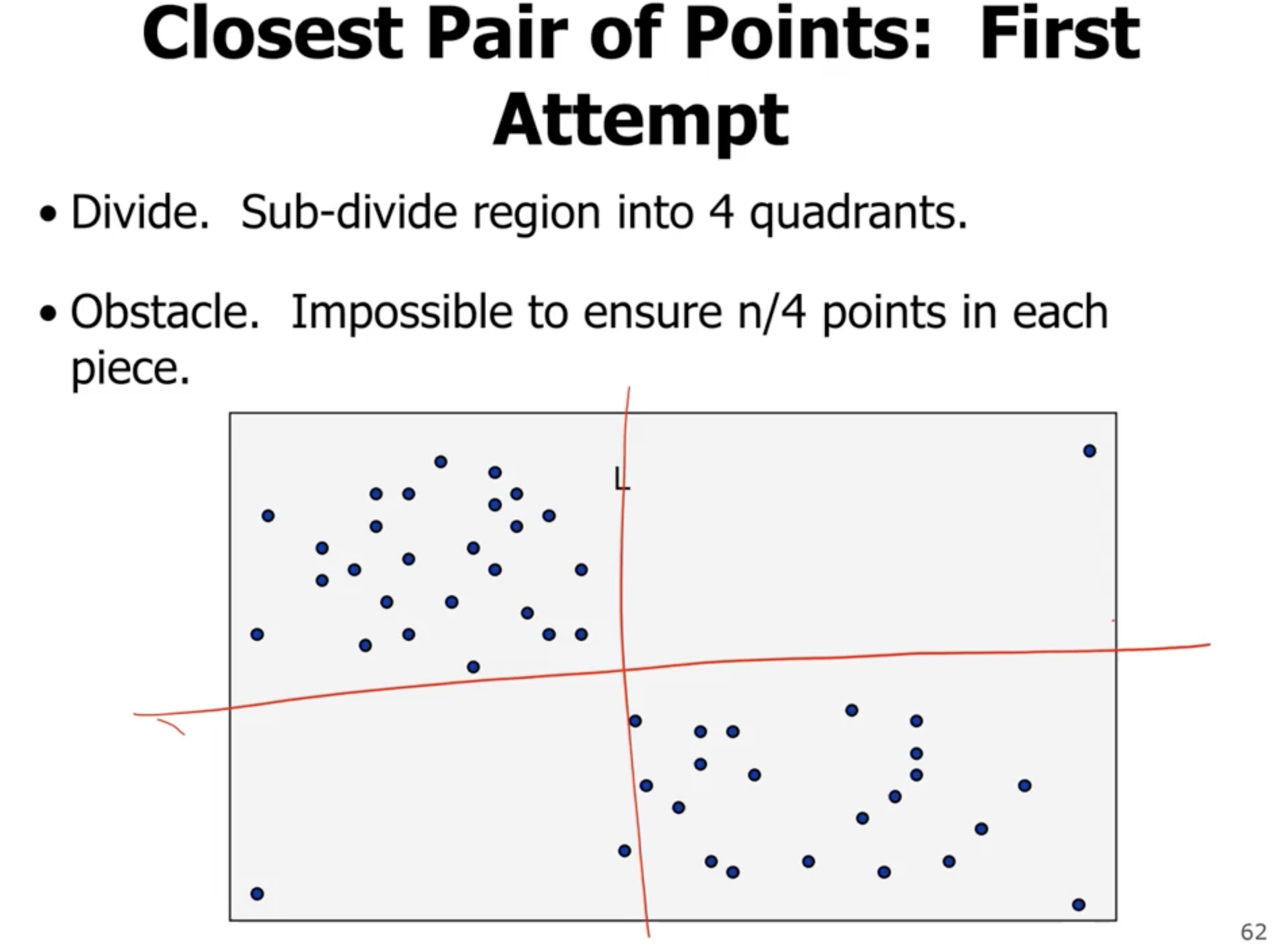

We can divide both the \( x \) and \( y \) axis in half:

Note: Usually if we divide our problem into subproblems of the same size, we get better asymptotic complexity.

So how would we combine the result? Its not easy to do better than \( \Theta(n^2) \) time. But, we want to do better.

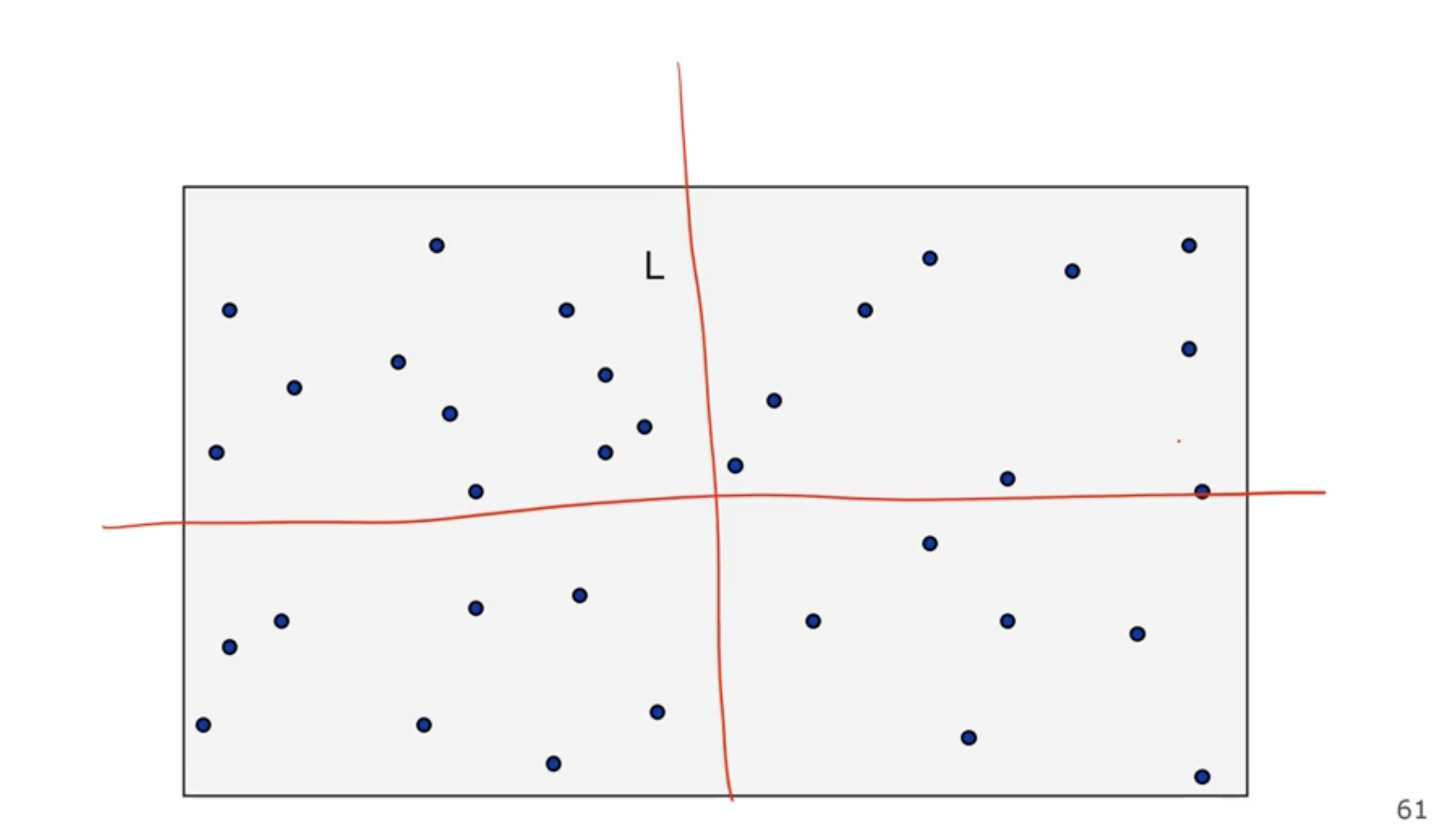

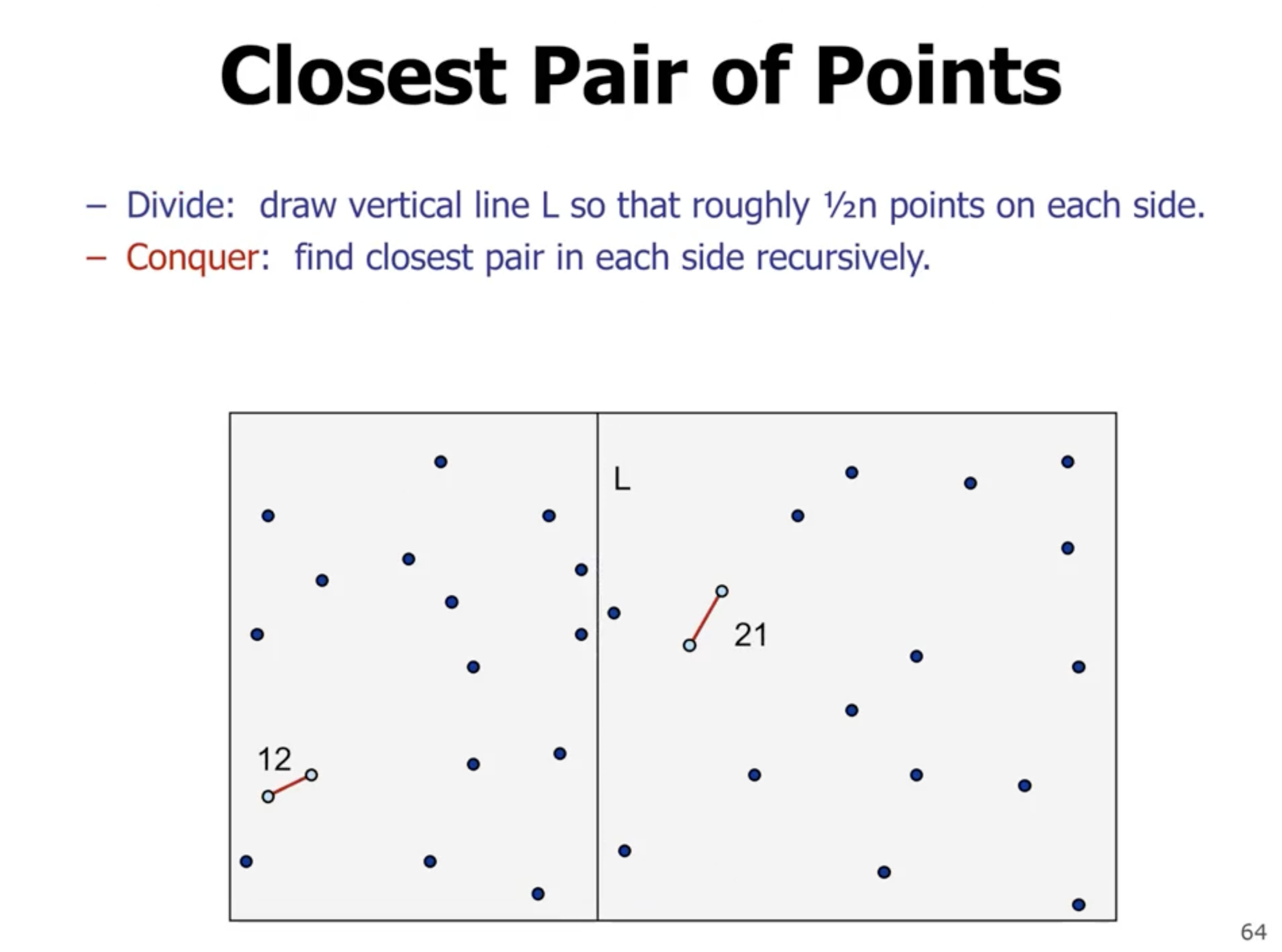

What if instead we just divide into 2 parts?

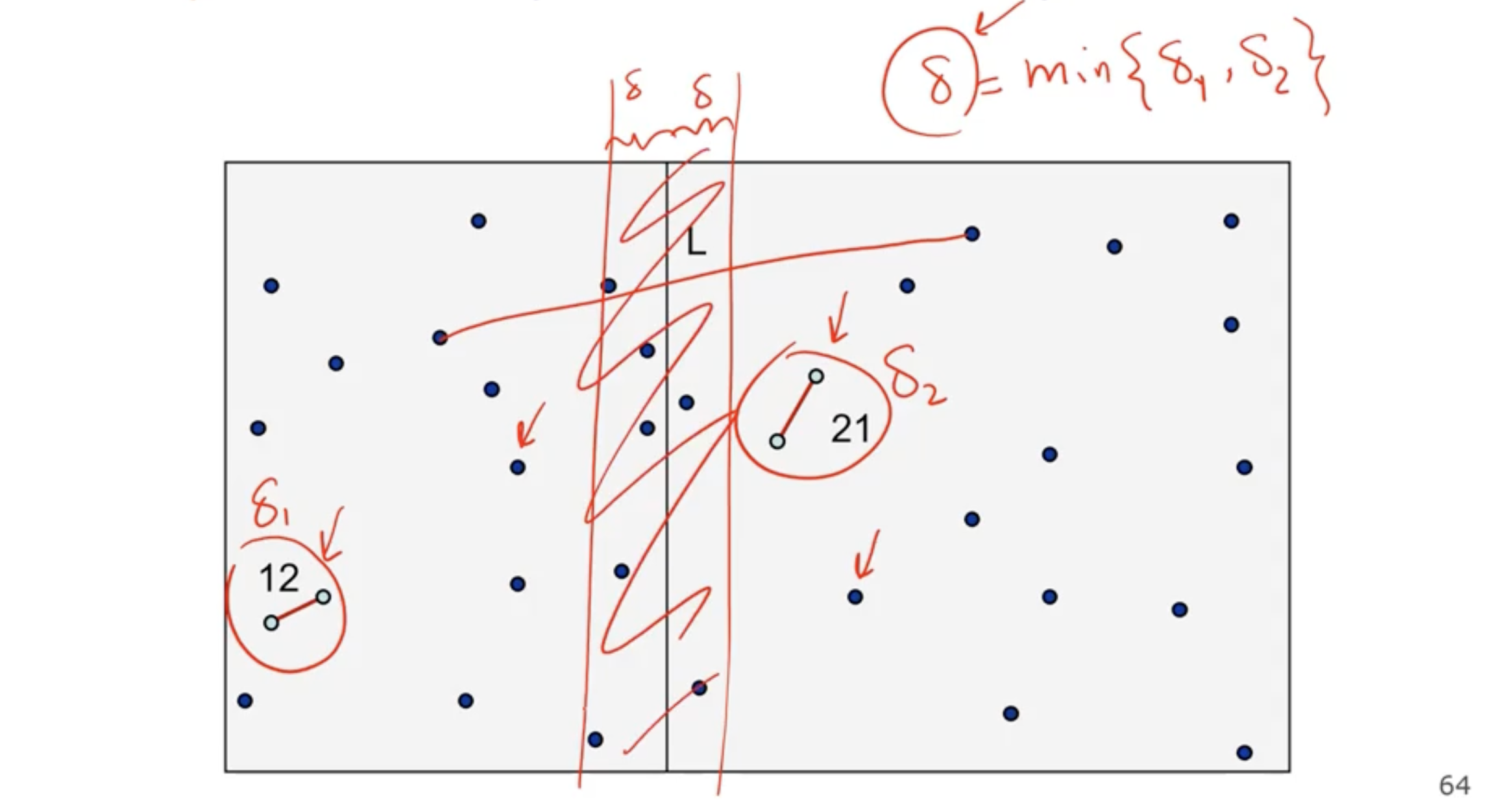

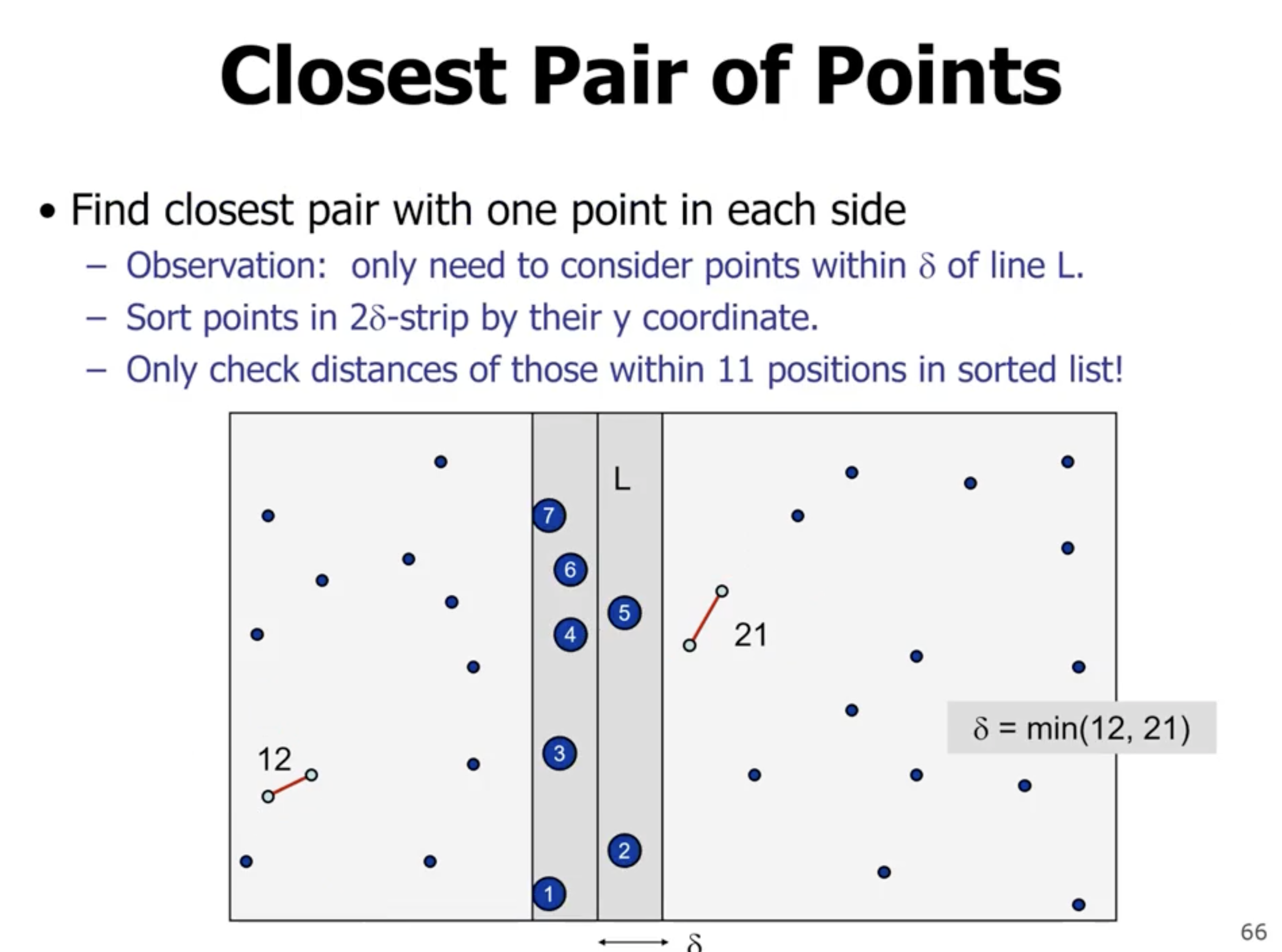

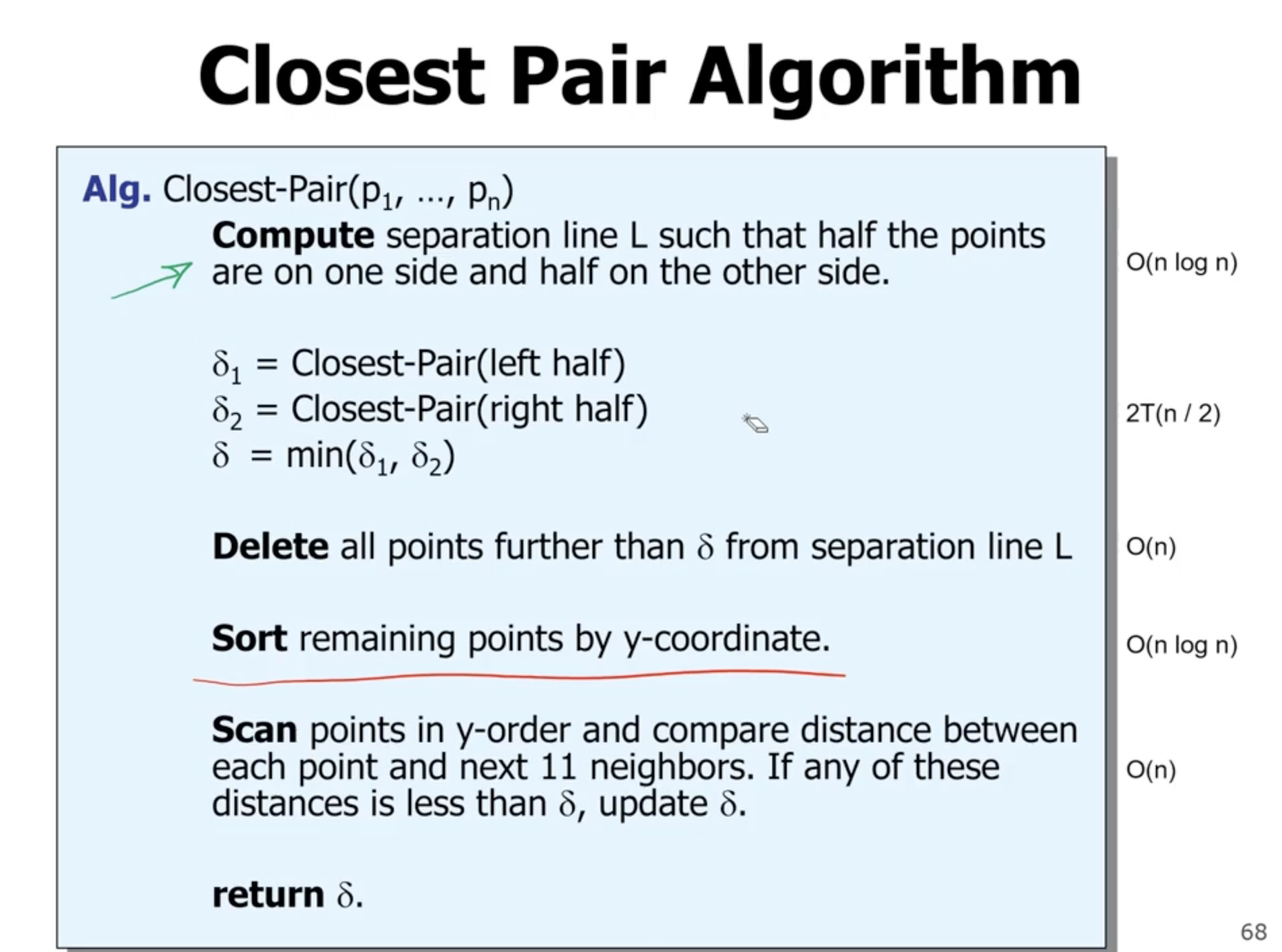

The problem is since we are comparing each point to each other point, we still end up with \( \Theta(n^2) \) . We eliminate points that are bigger than the 2 subarray returns. We can take the min of the 2 subarray returns, and create a boundary on the left and right of the division and check those points only.

However, the problem is we don’t know whether or not all points will fall in the center band.

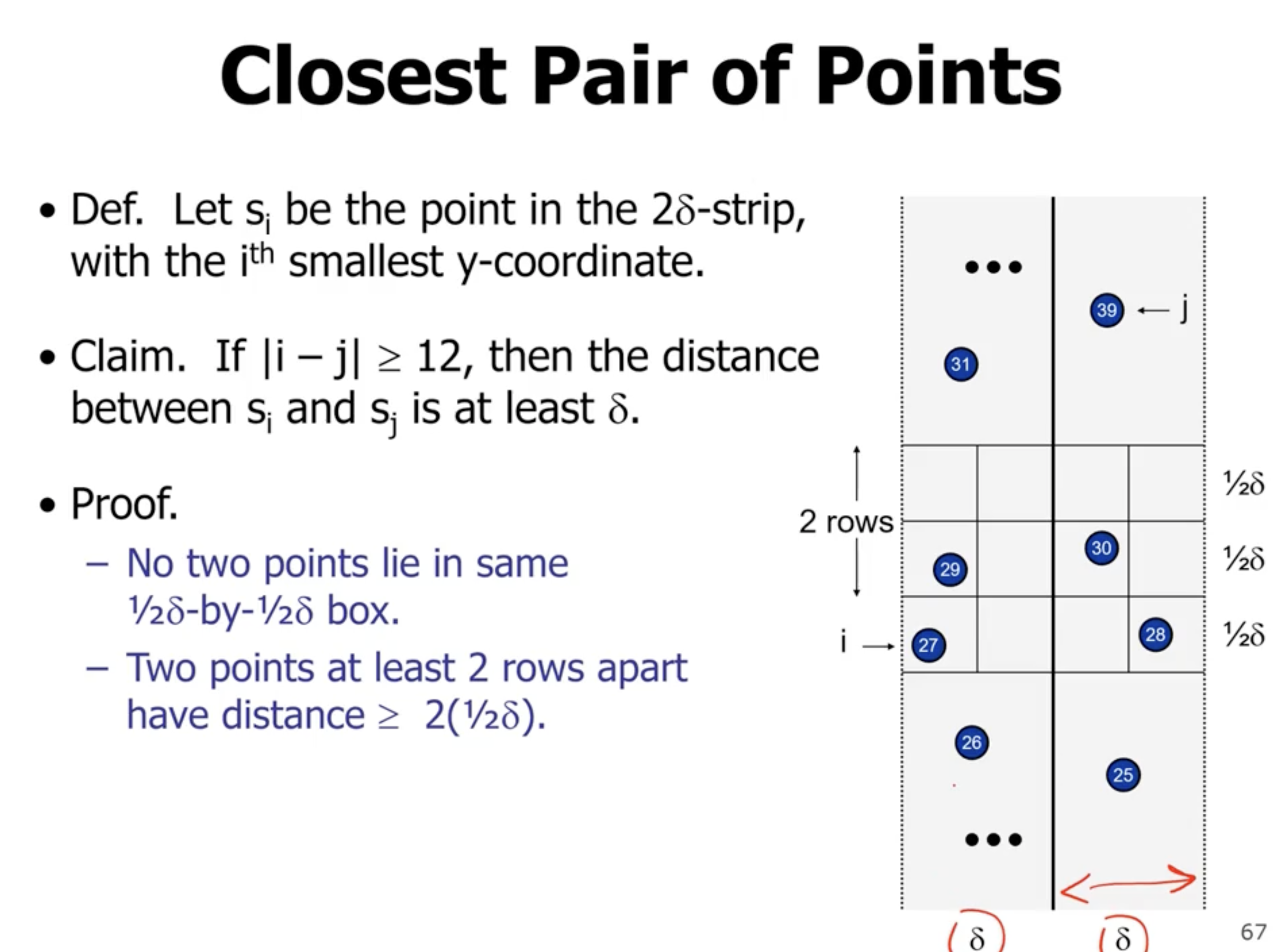

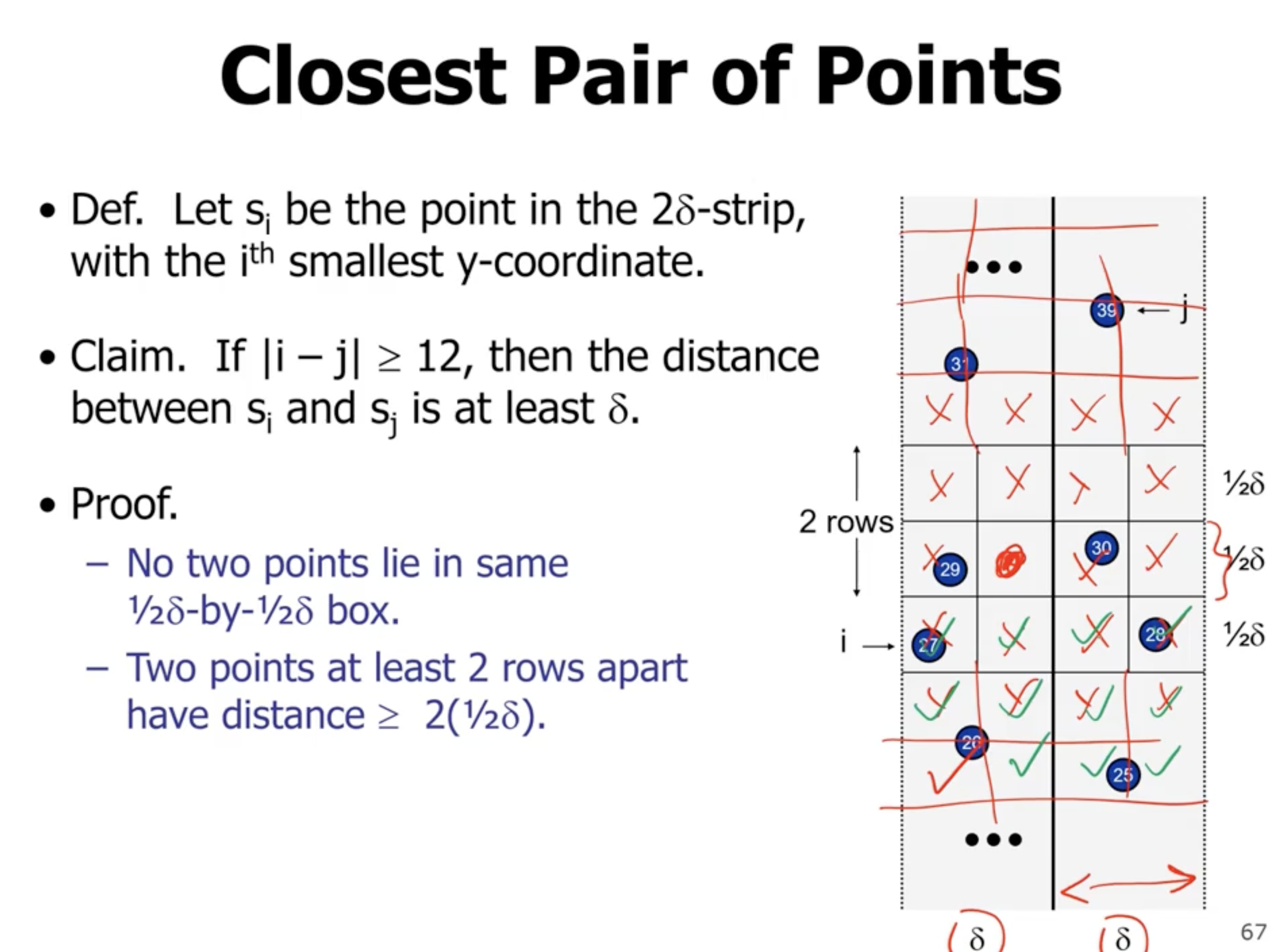

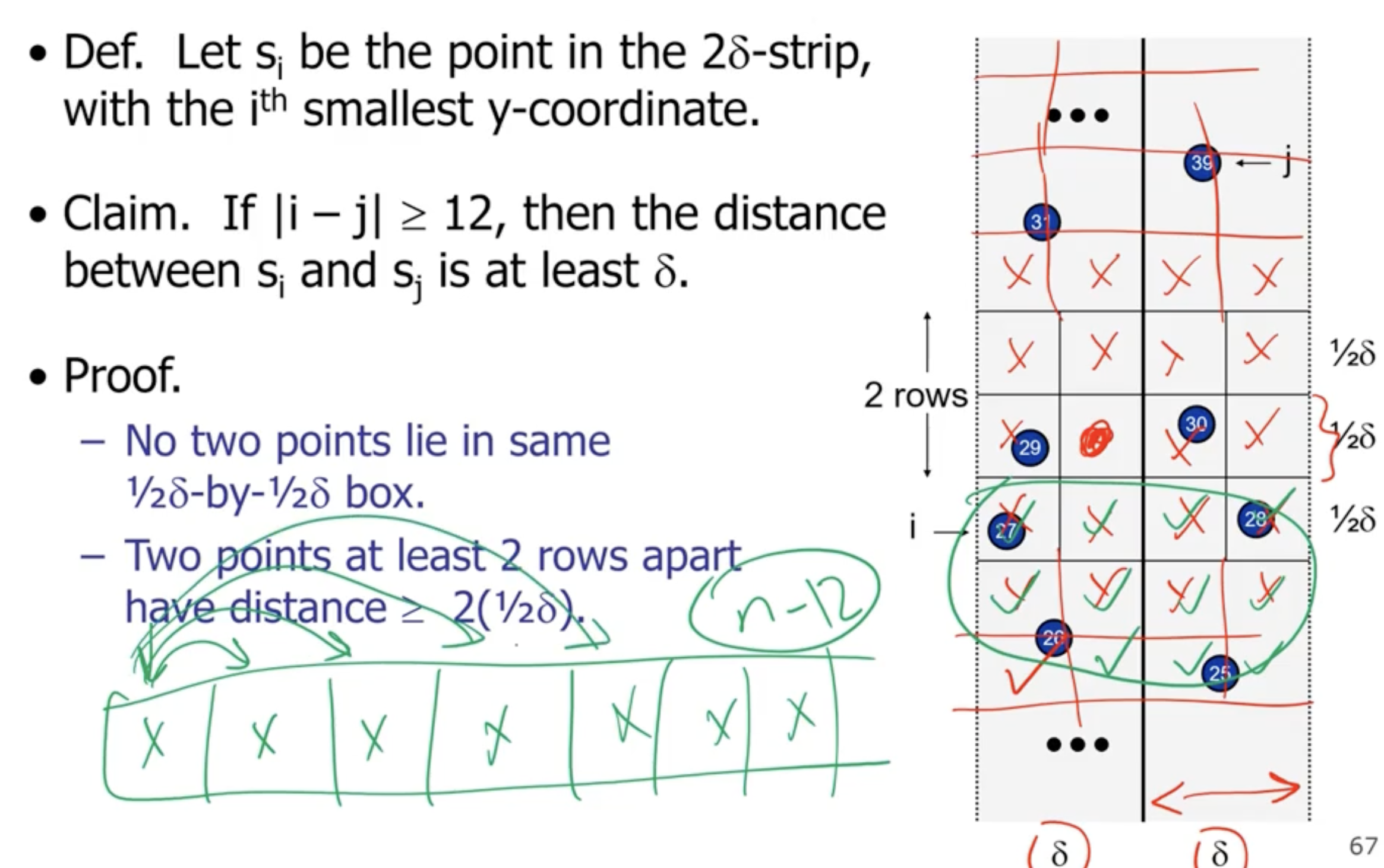

We can also enforce the restriction in the \( y \) direction. So if we sort the numbers on the \( y \) coordinates, and the index is greater than or equal to the min number, then they will be at least that far away.

If 2 points fall inside one grid square, then the distance between them will be less than the min of the subarrays.

So we loop for each item 12 times, so we get a complexity of \( \Theta(n) \) for combine.

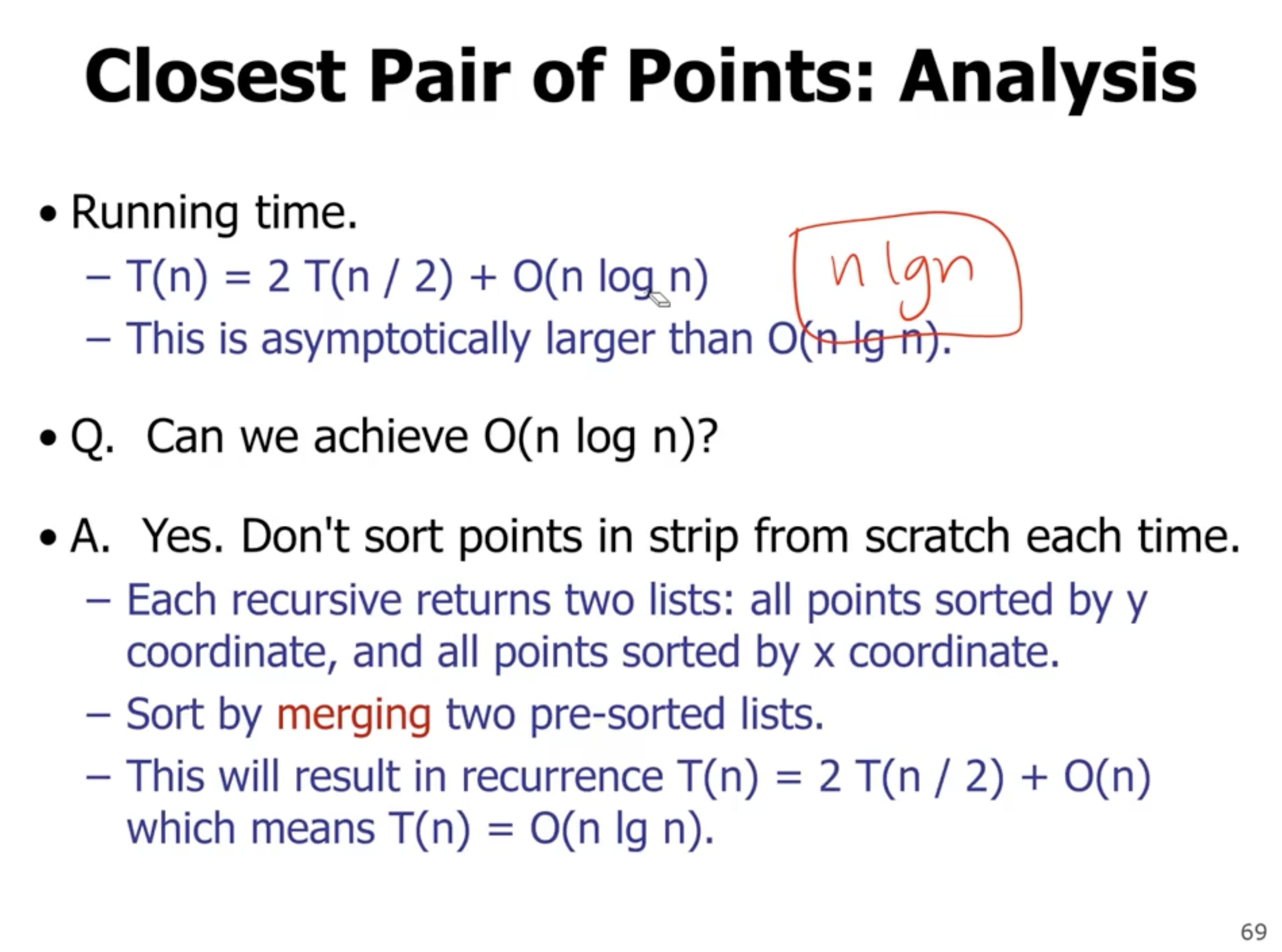

So, this results in a \( \Theta(n \lg n) \) runtime complexity. However, this is no better than just sorting by the coordinates in the beginning. So how can we do better?

We can put the compute step outside of the recursion. We can also do the \( y \) coordinate sorting inside the recursion.

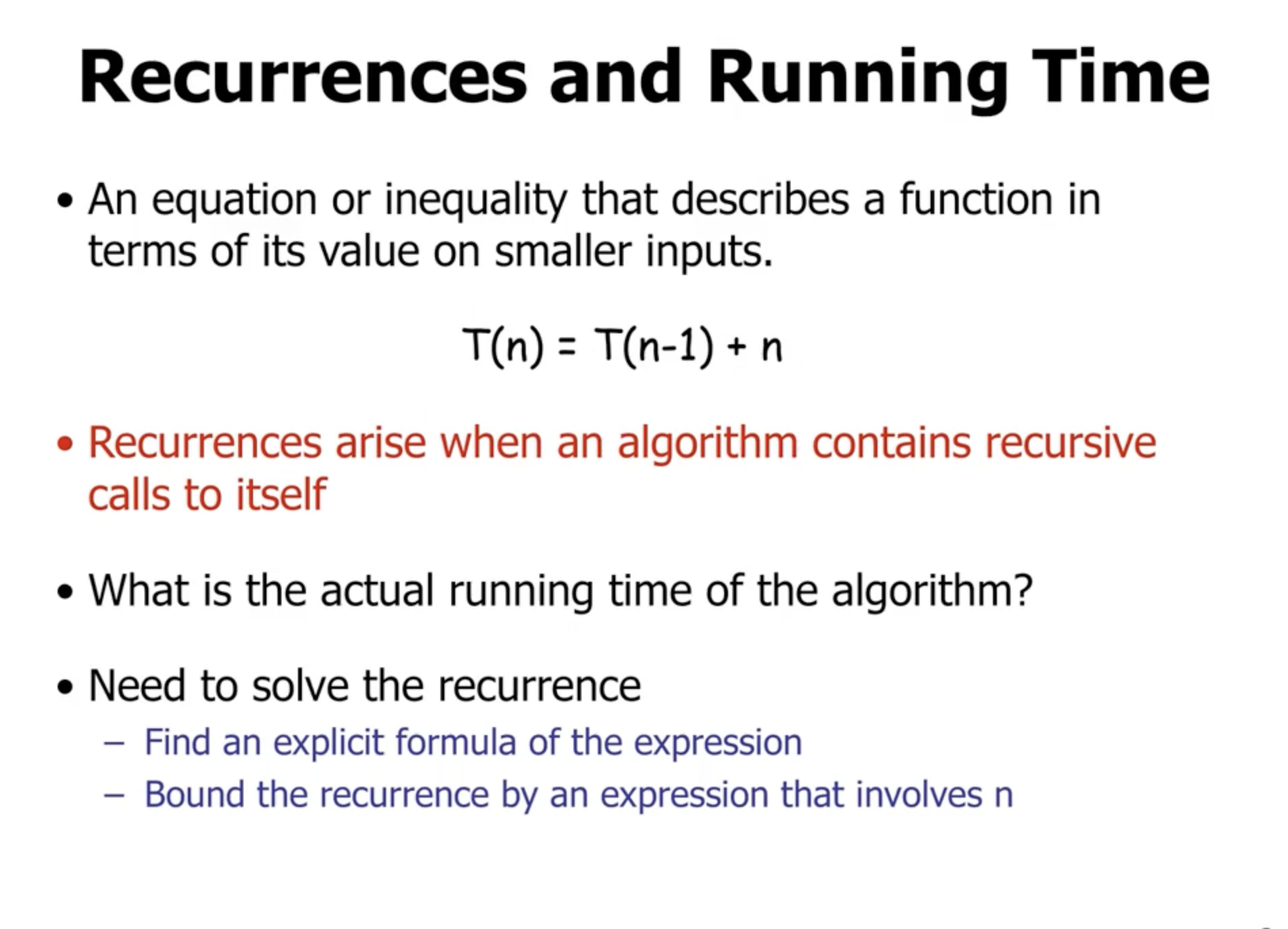

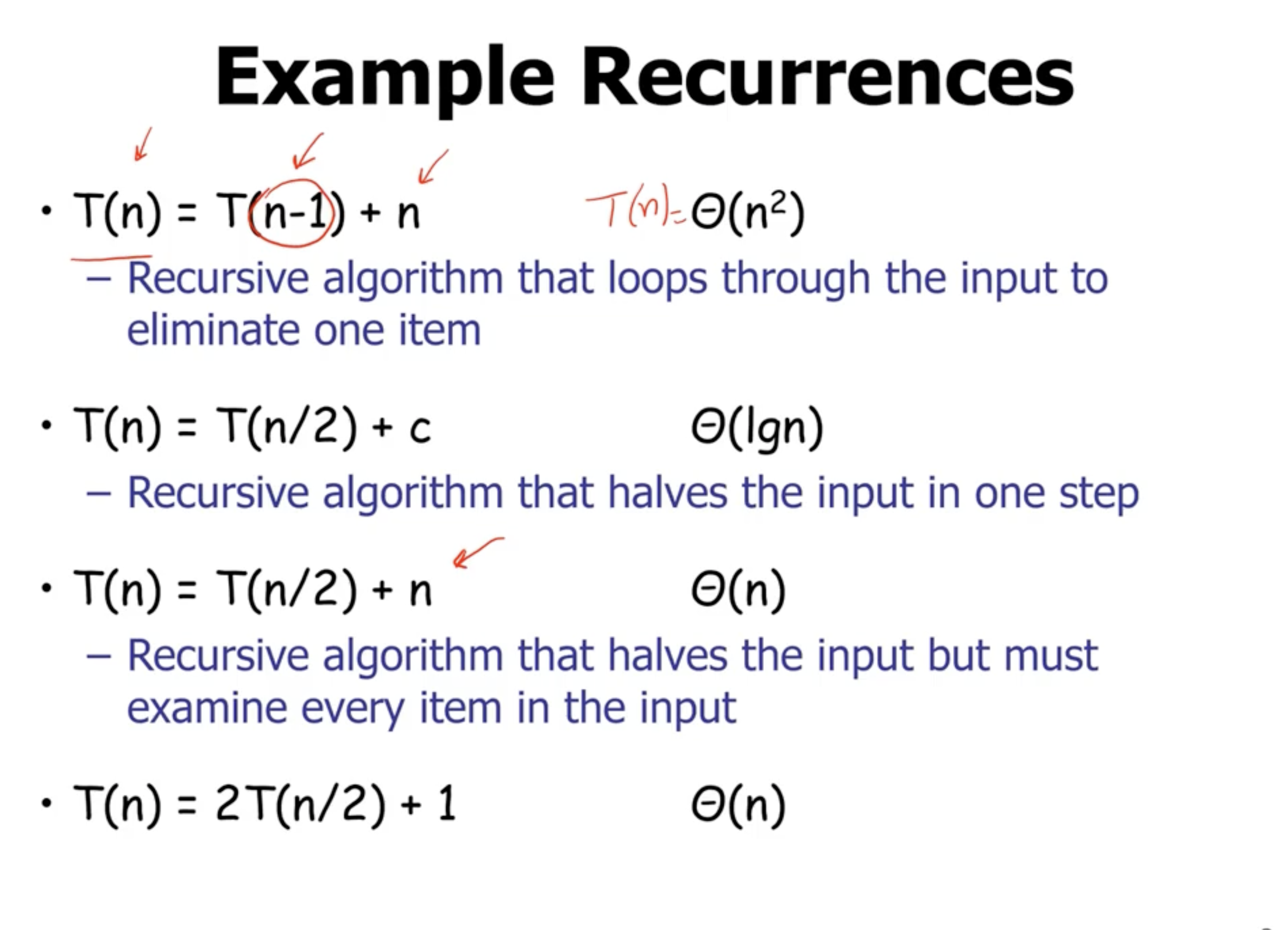

Solving recurrences #

So how can we go from the recurrences to the solutions?

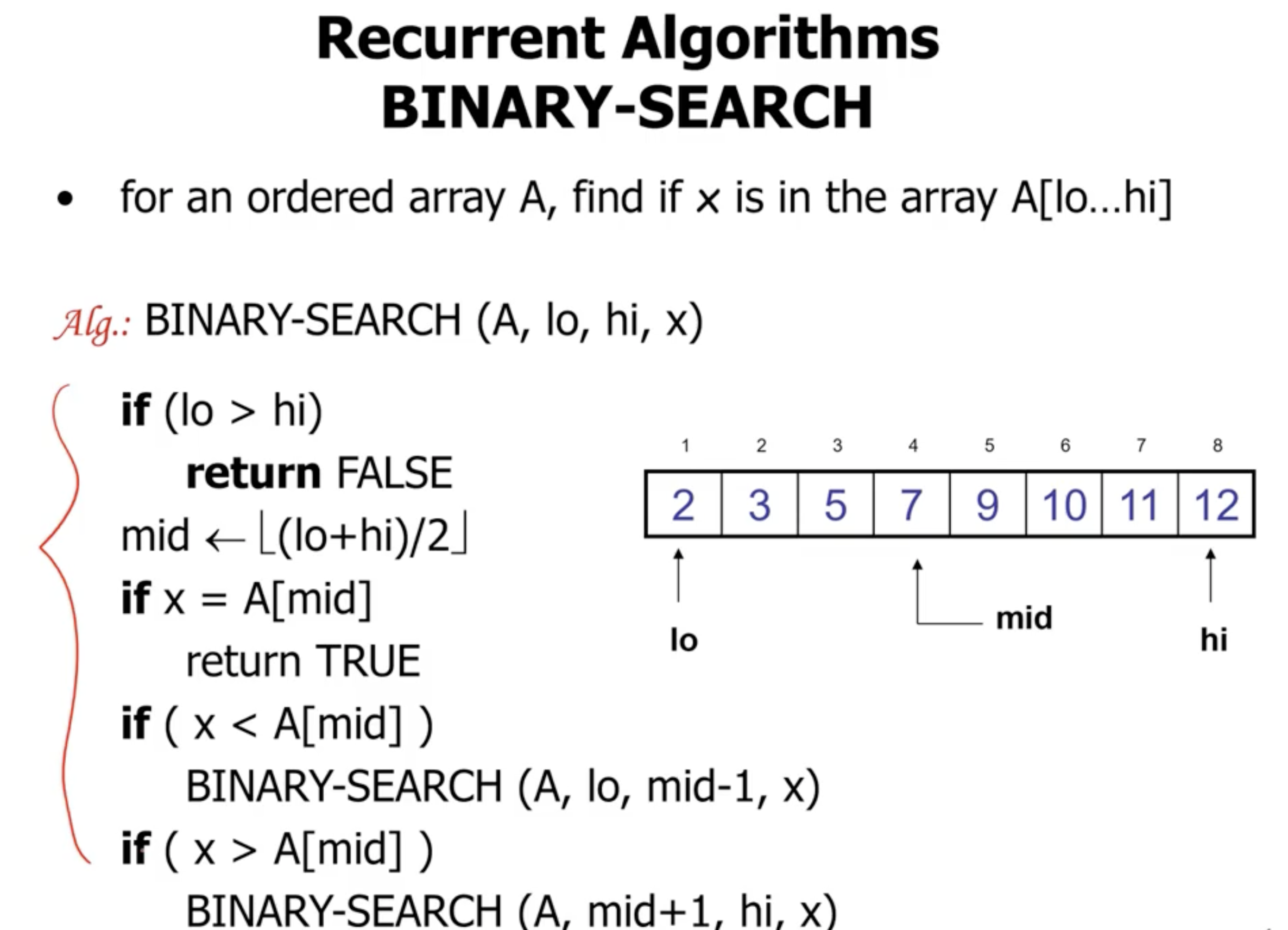

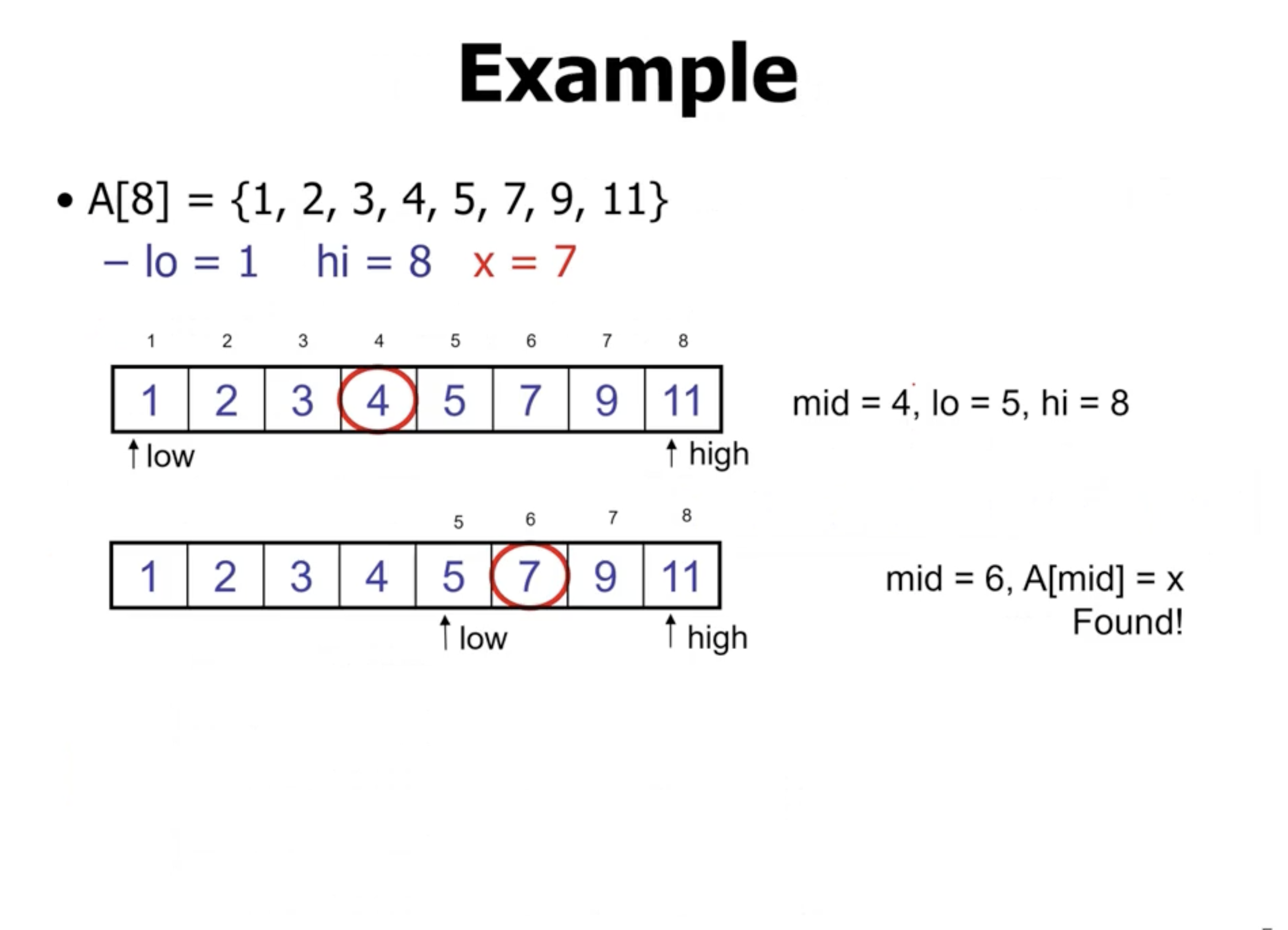

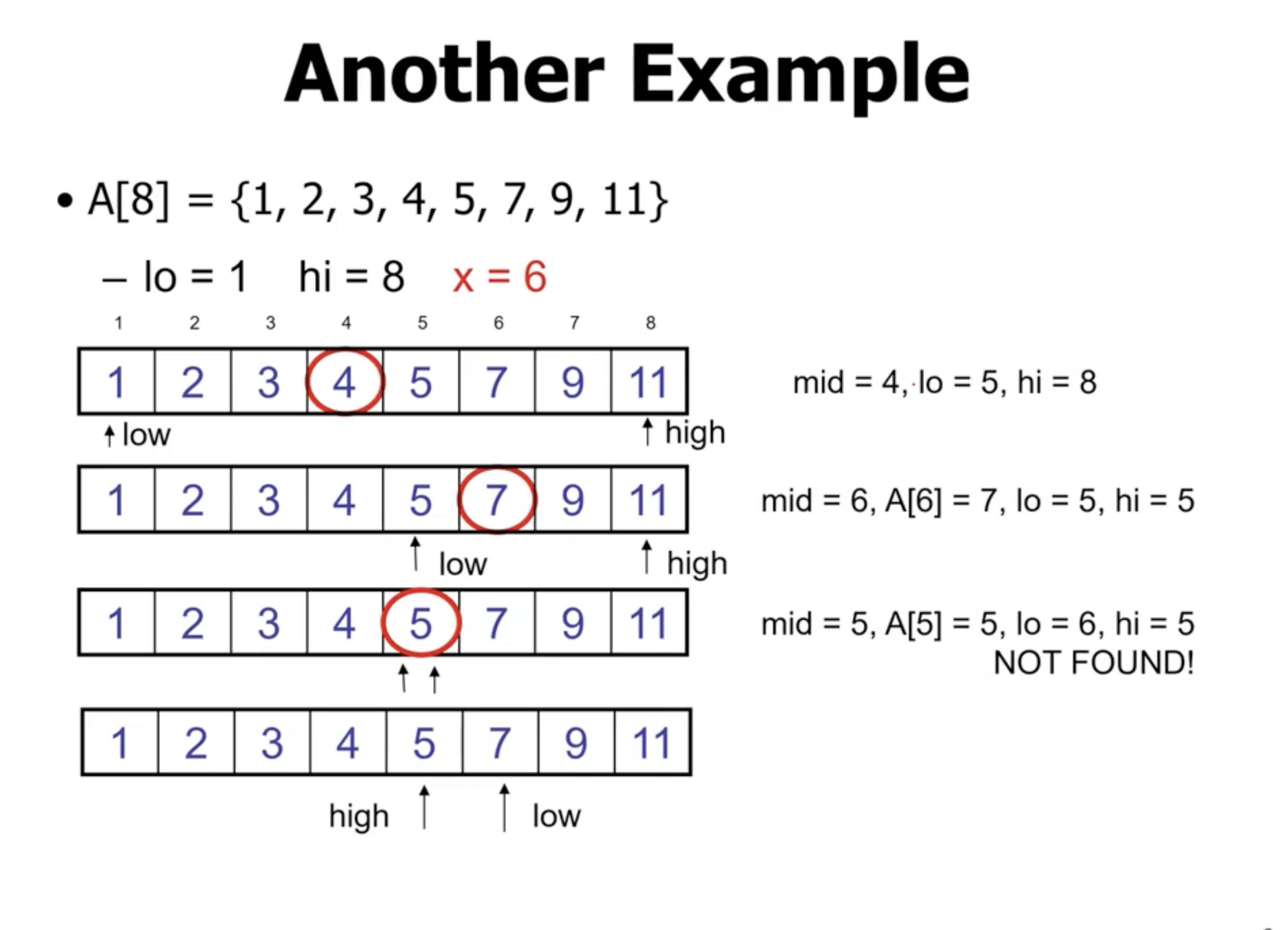

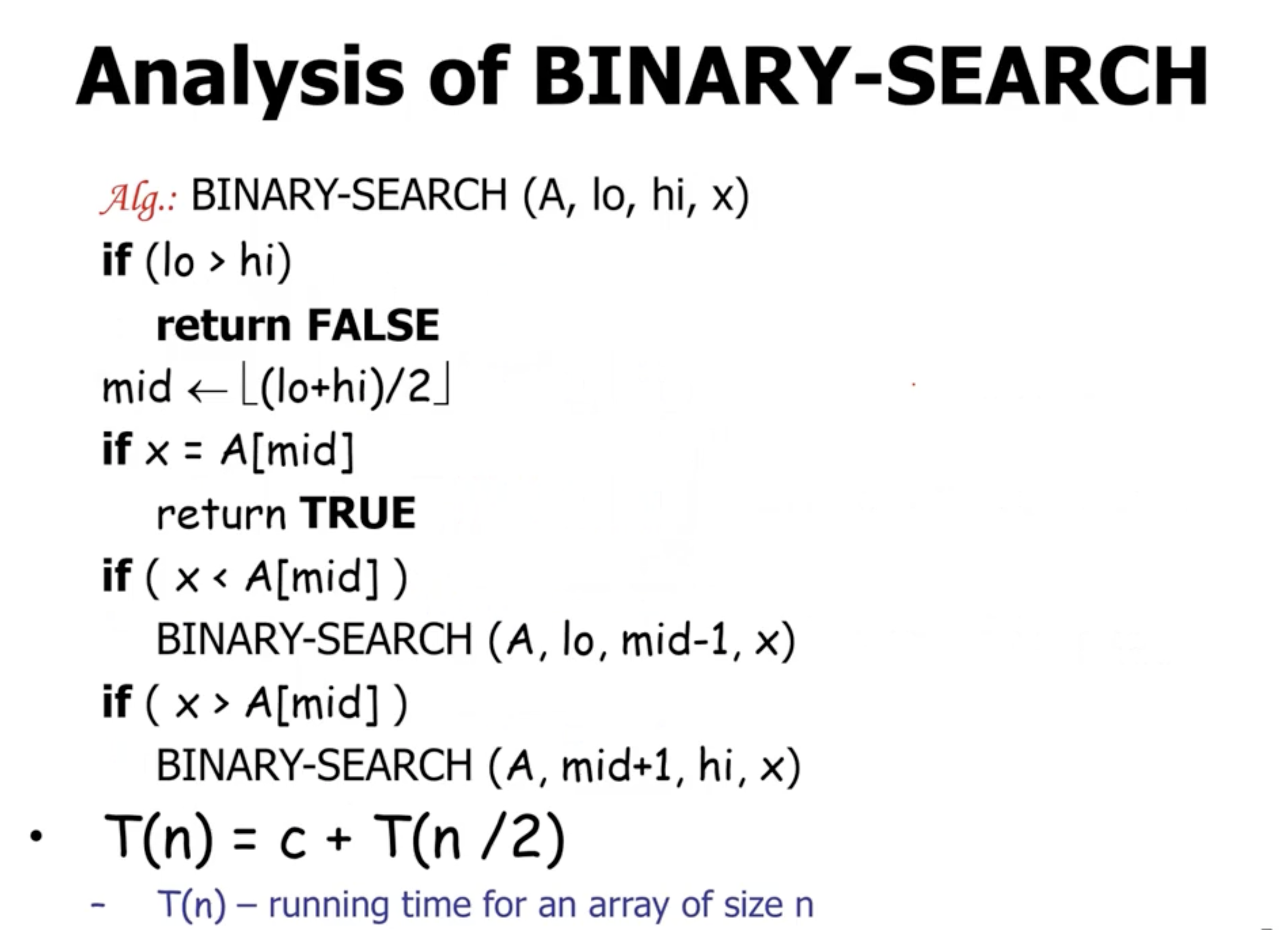

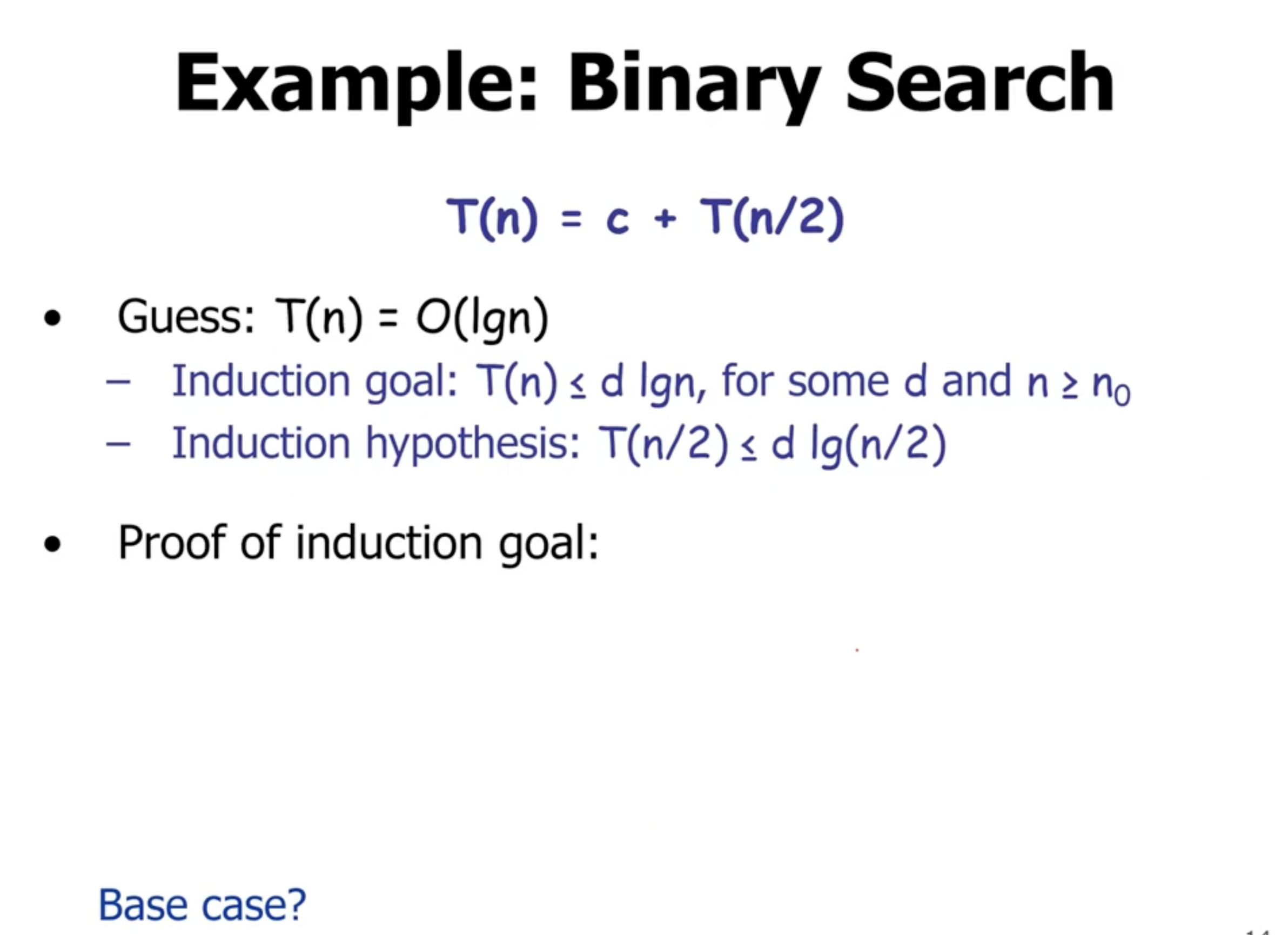

Binary search recurrences #

If lo > hi or if we find the value we’re looking for, the complexity is

\( \Theta(1) \)

.

On the recursive call, we have a complexity of

\[\begin{aligned}

T(n) &= T \left( \frac{n}{2} \right) + \Theta(1) + \Theta(1) + \Theta(1) \\

&= T \left( \frac{n}{2} \right) + c \\

&= O(\lg n)

\end{aligned}\]

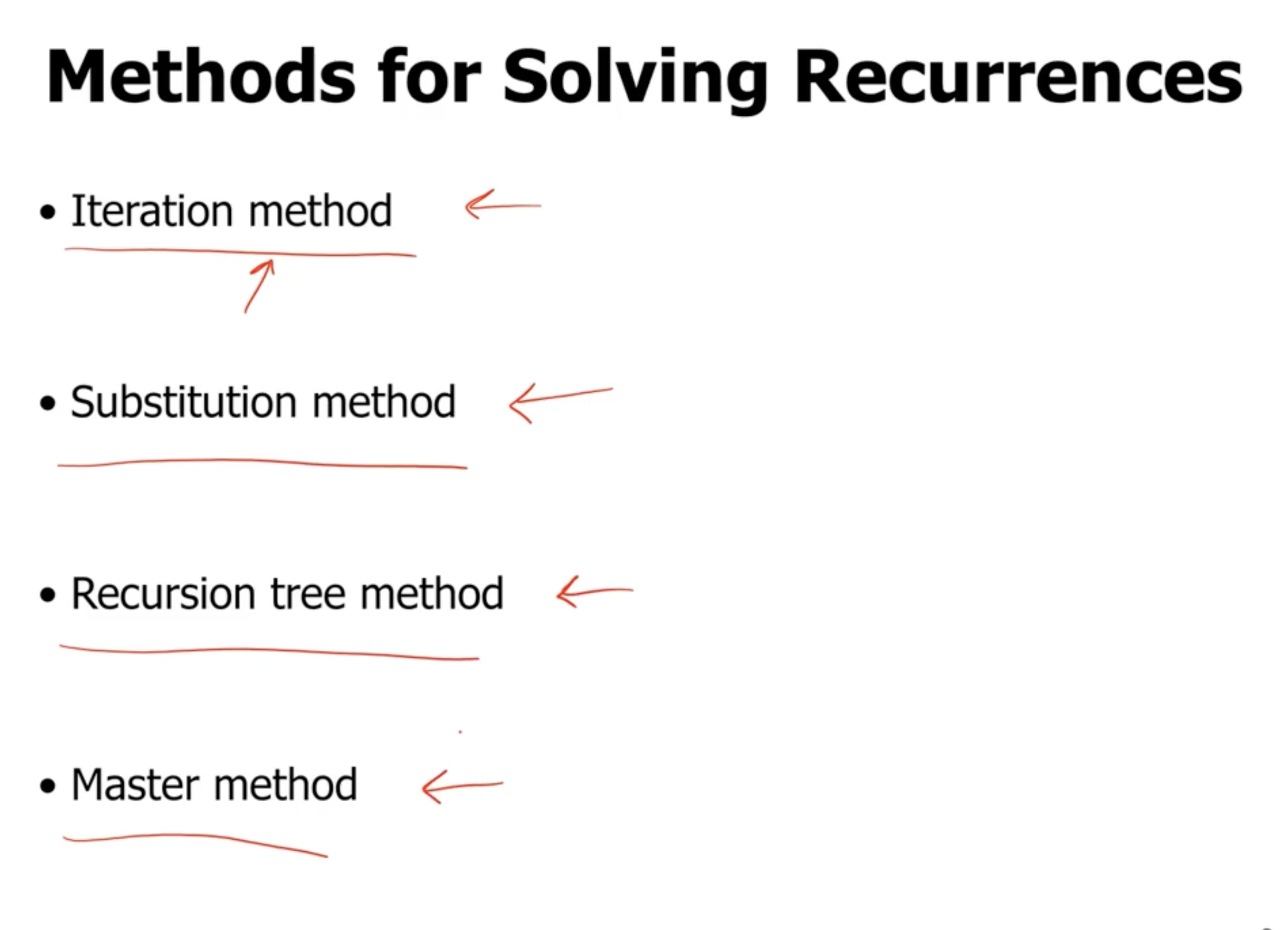

Methods for solving recurrences #

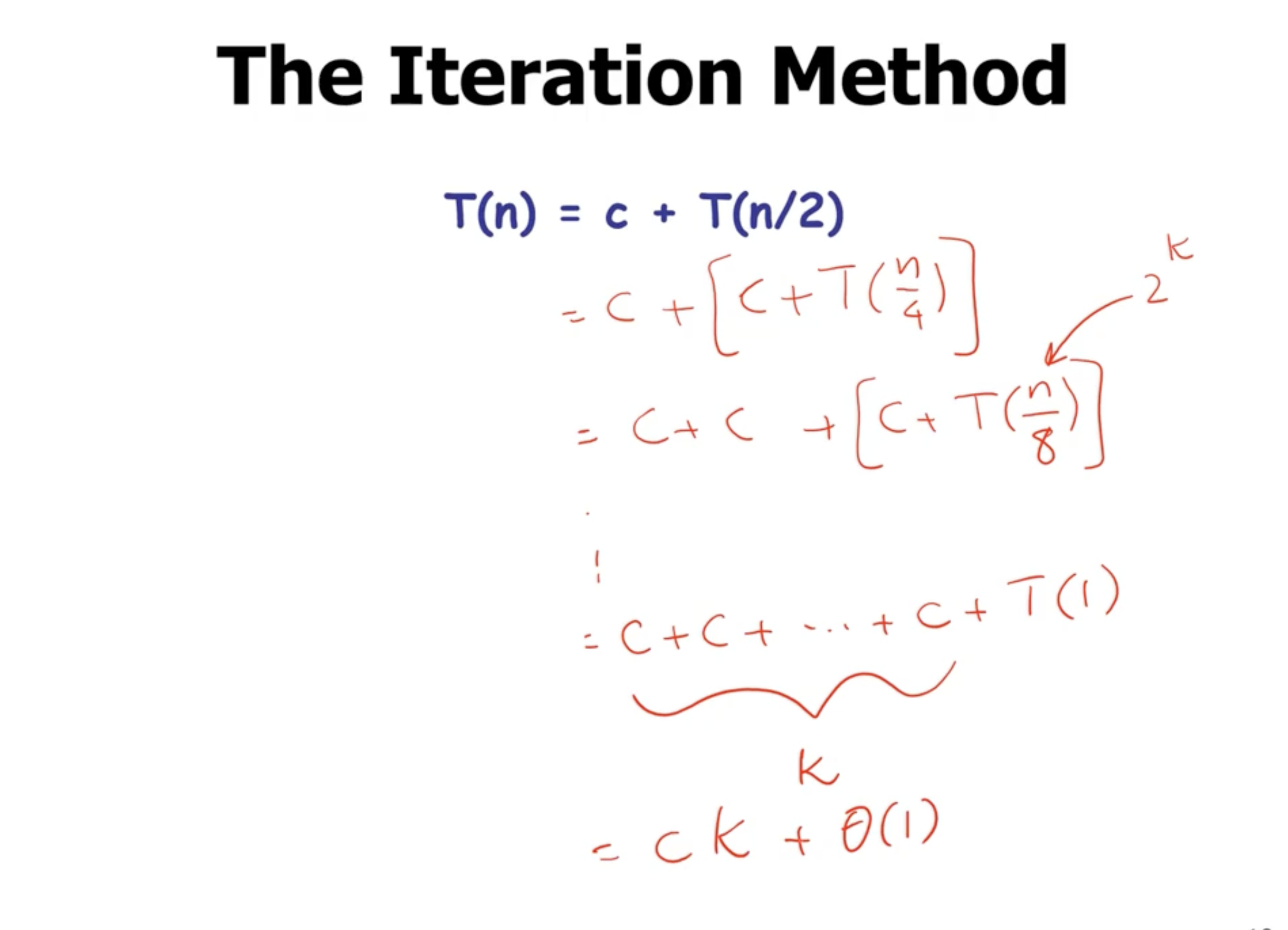

Iteration method #

Here \( k = \lg n \) . So overall we get \[\begin{aligned} &= c \lg n + \Theta(1) \\ &= \Theta( \lg n) \end{aligned}\]

What if \( n \) is not a power of 2? Asymptotically it will still be a linear complexity.

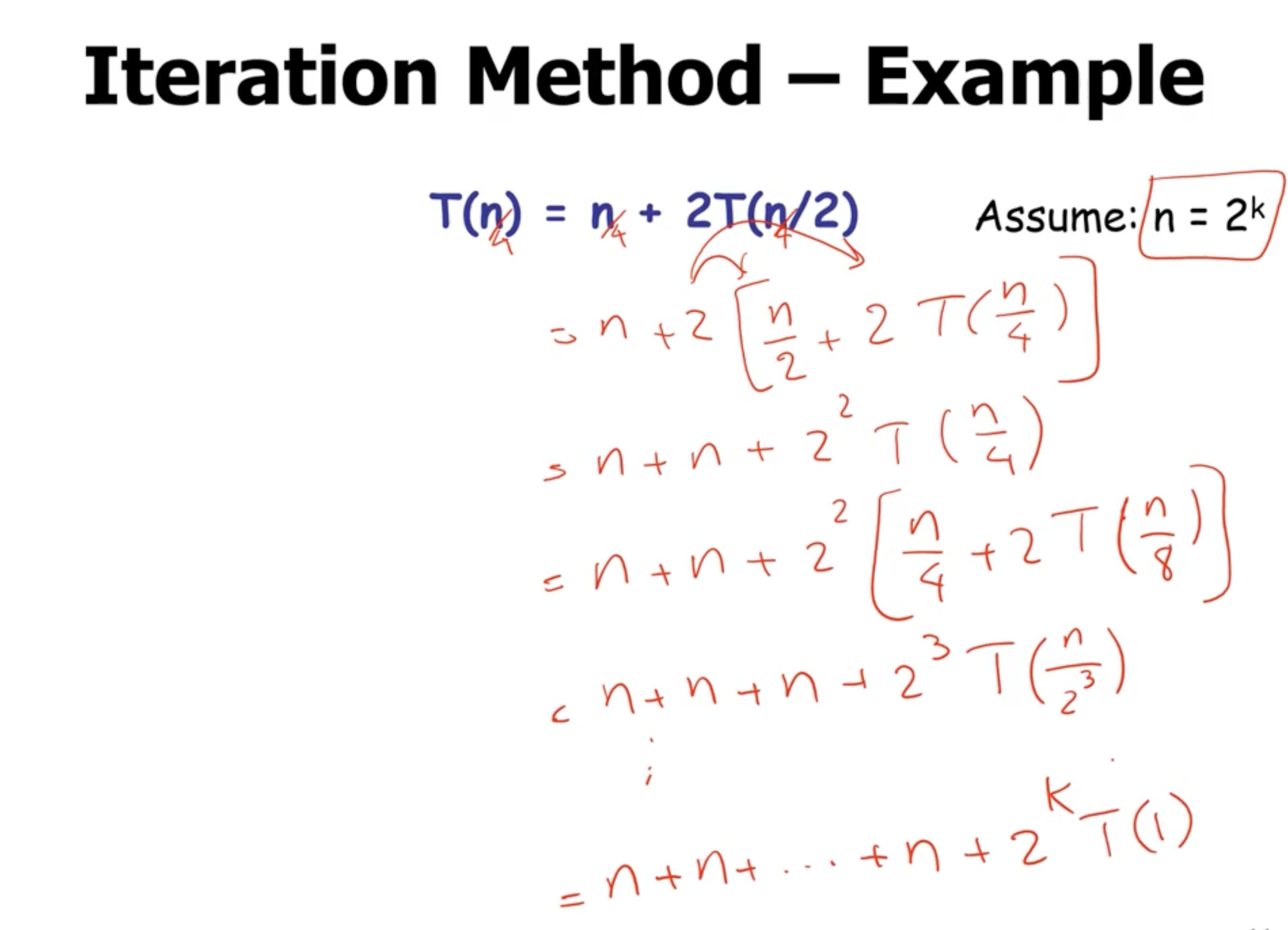

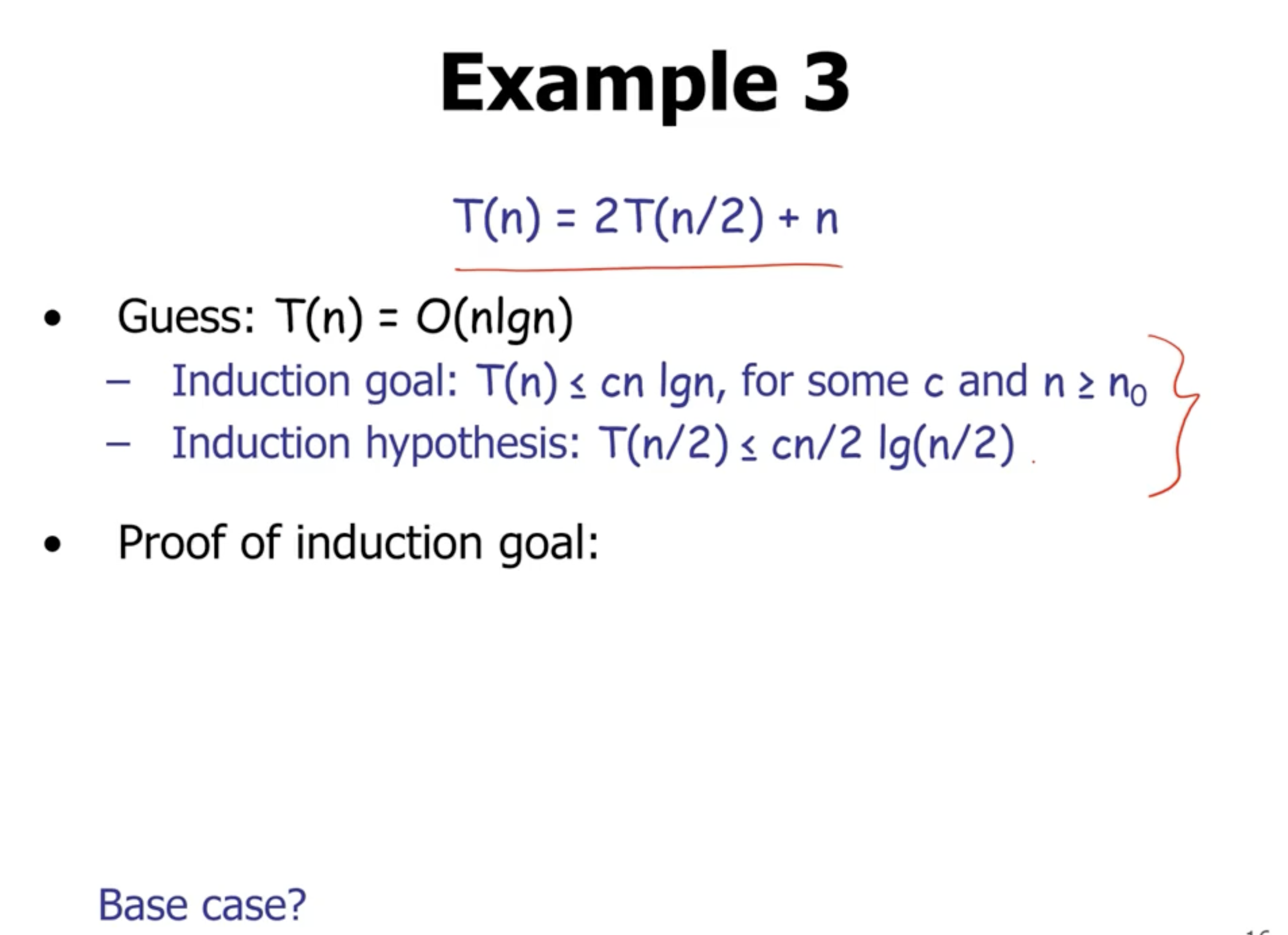

So since we complete \( n \) steps \( k \) times, plus \( 2^k \) constant times. Since \( k = \lg n \) the entire thing equals \[\begin{aligned} &= n \lg n + n \\ &= \Theta(n \lg n) \end{aligned}\]

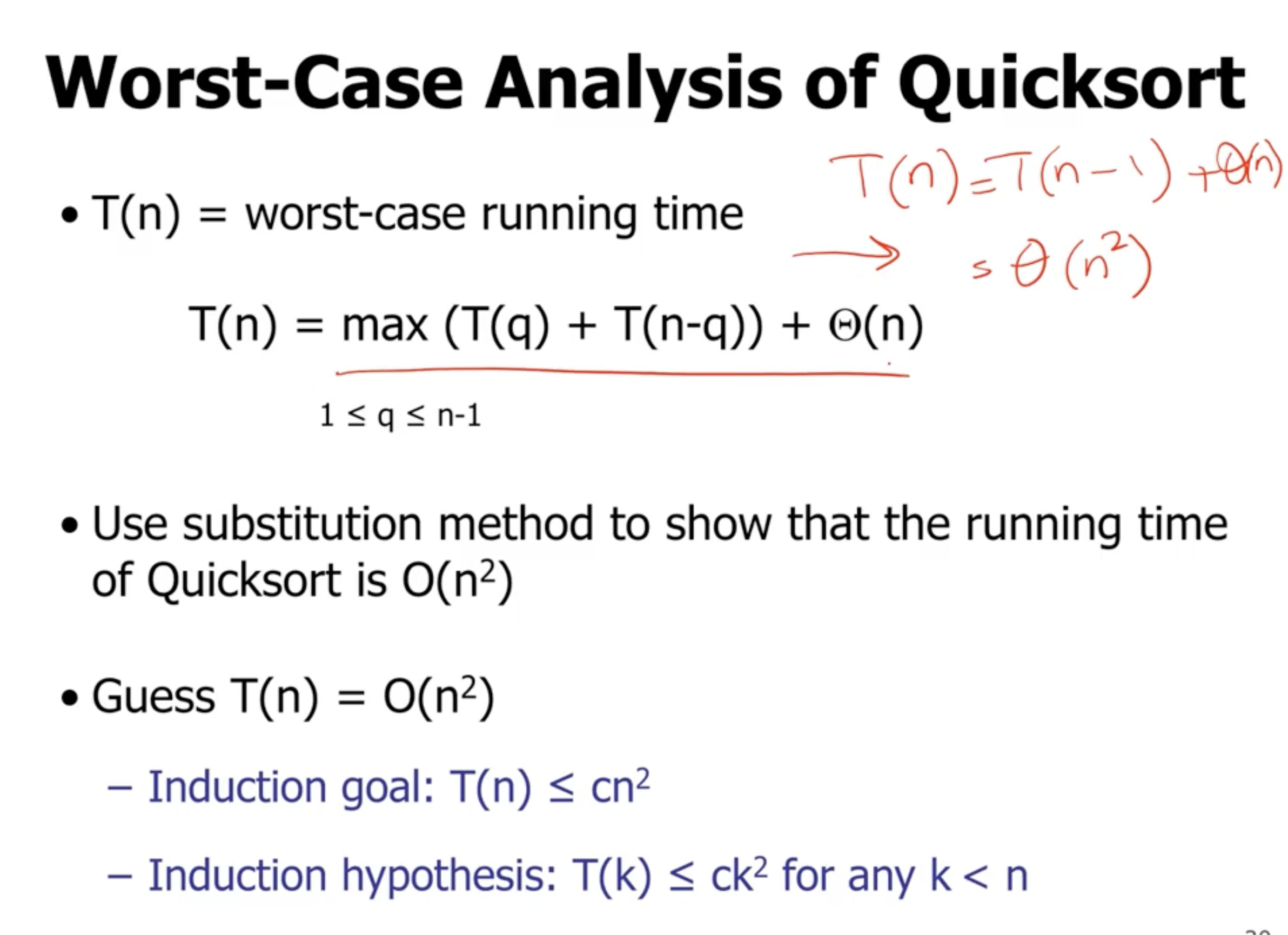

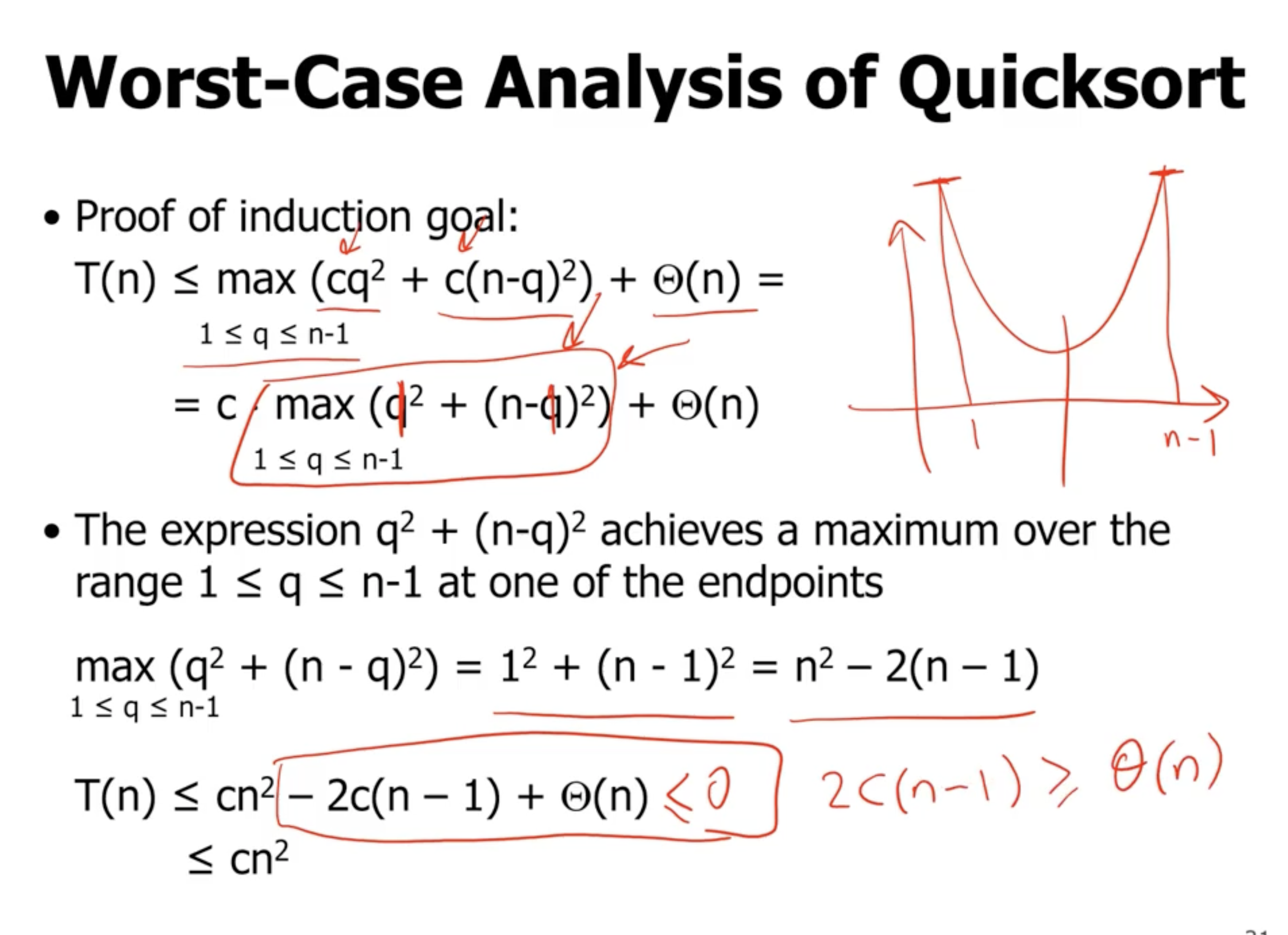

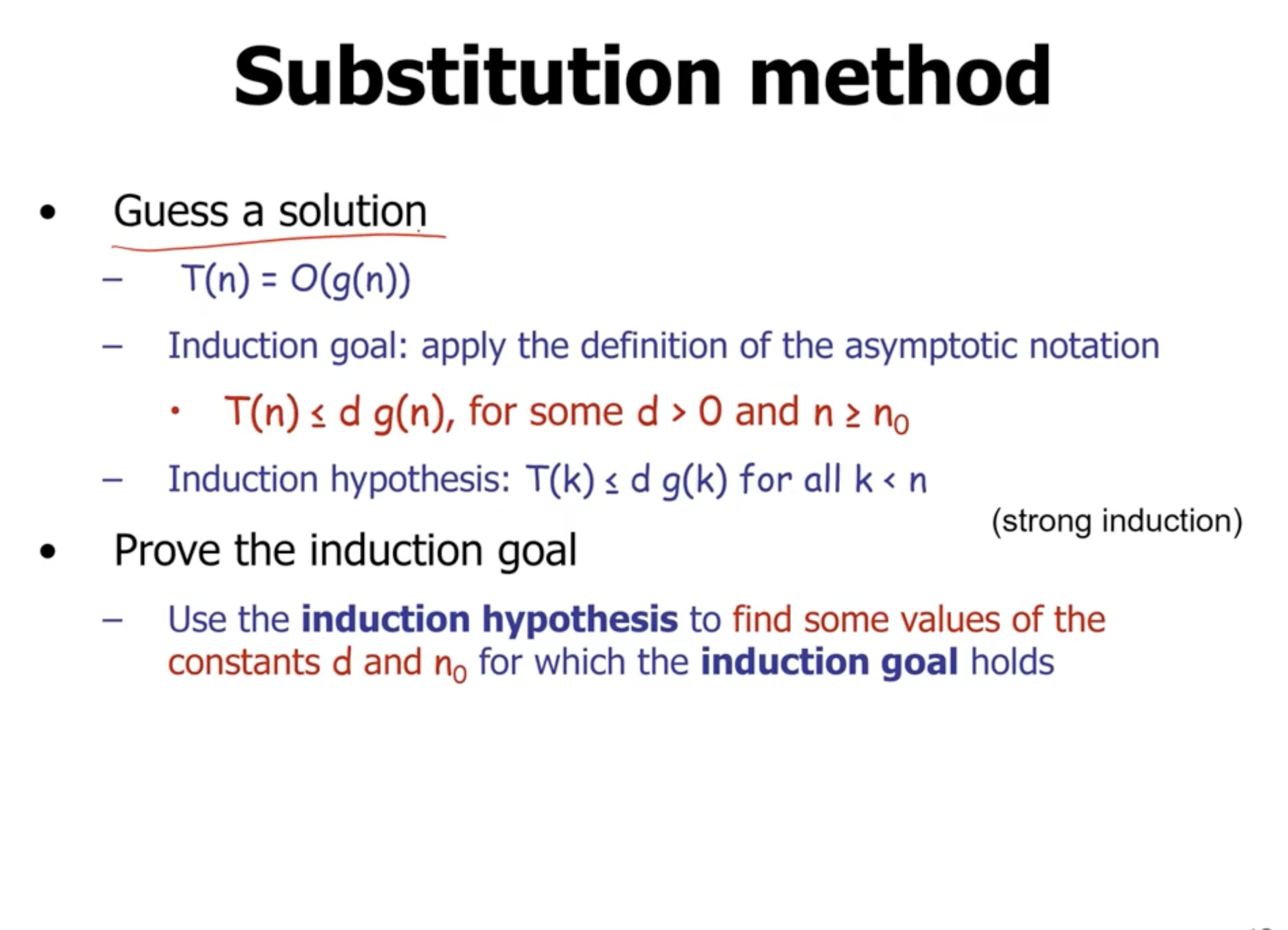

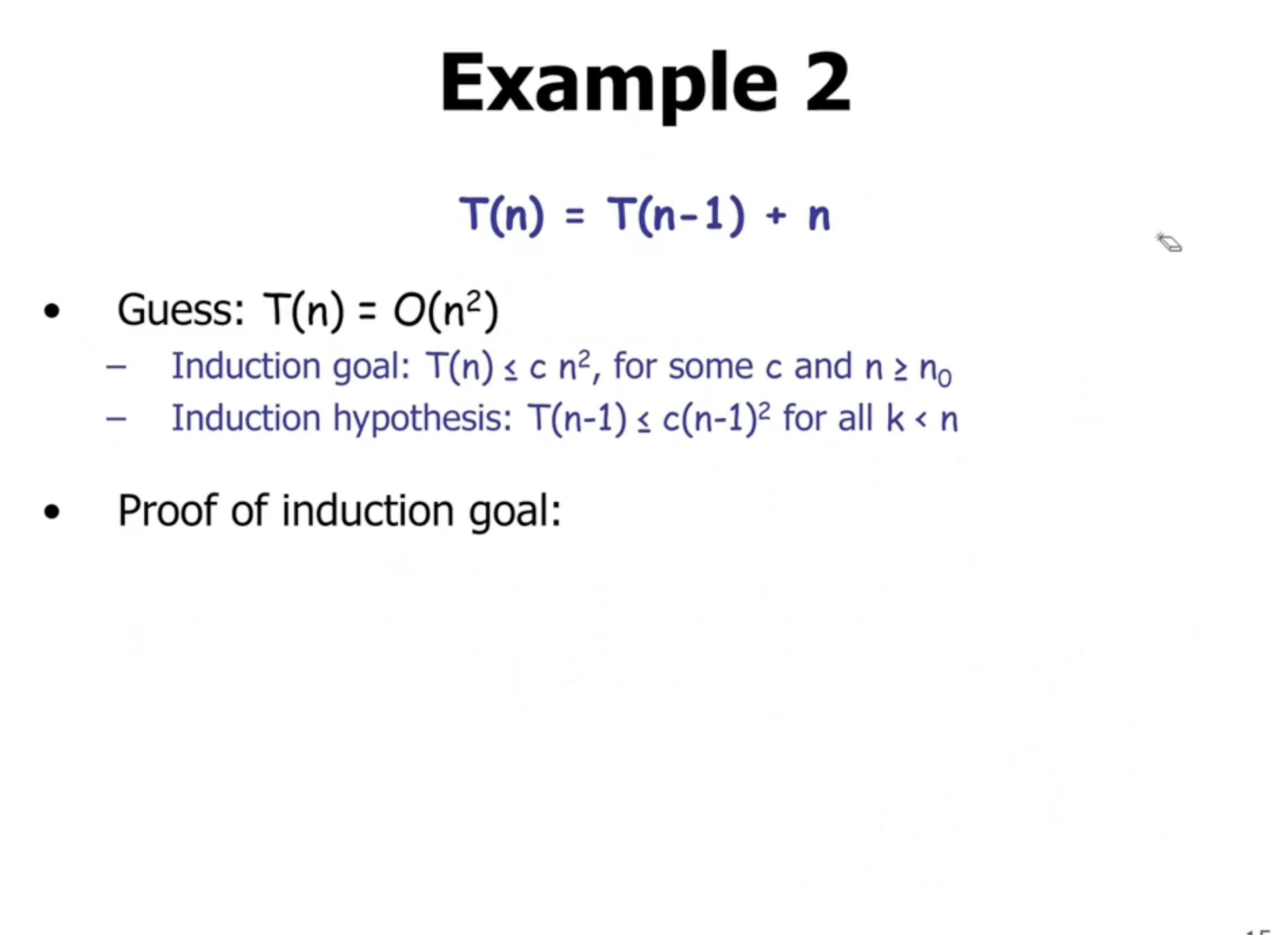

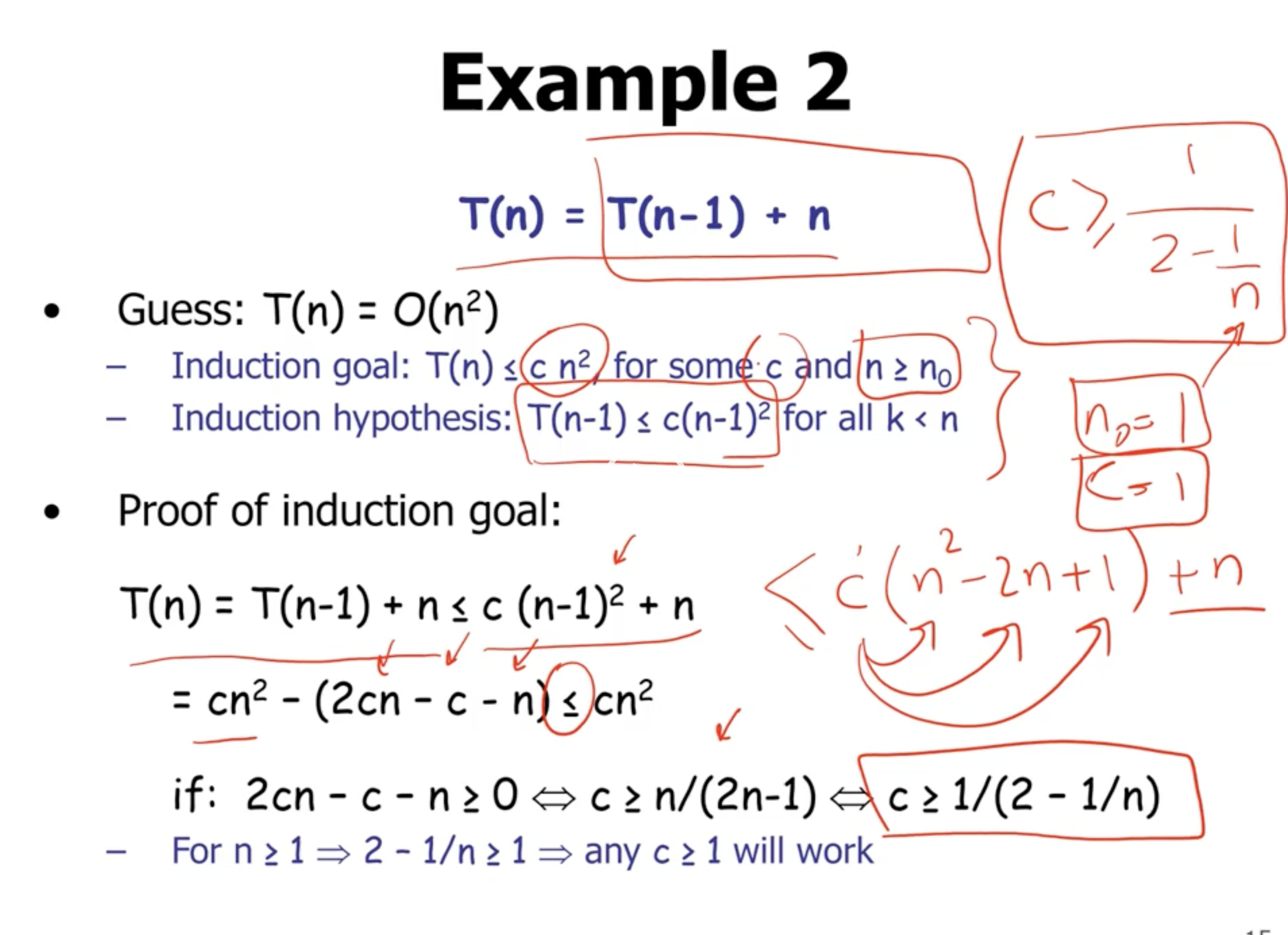

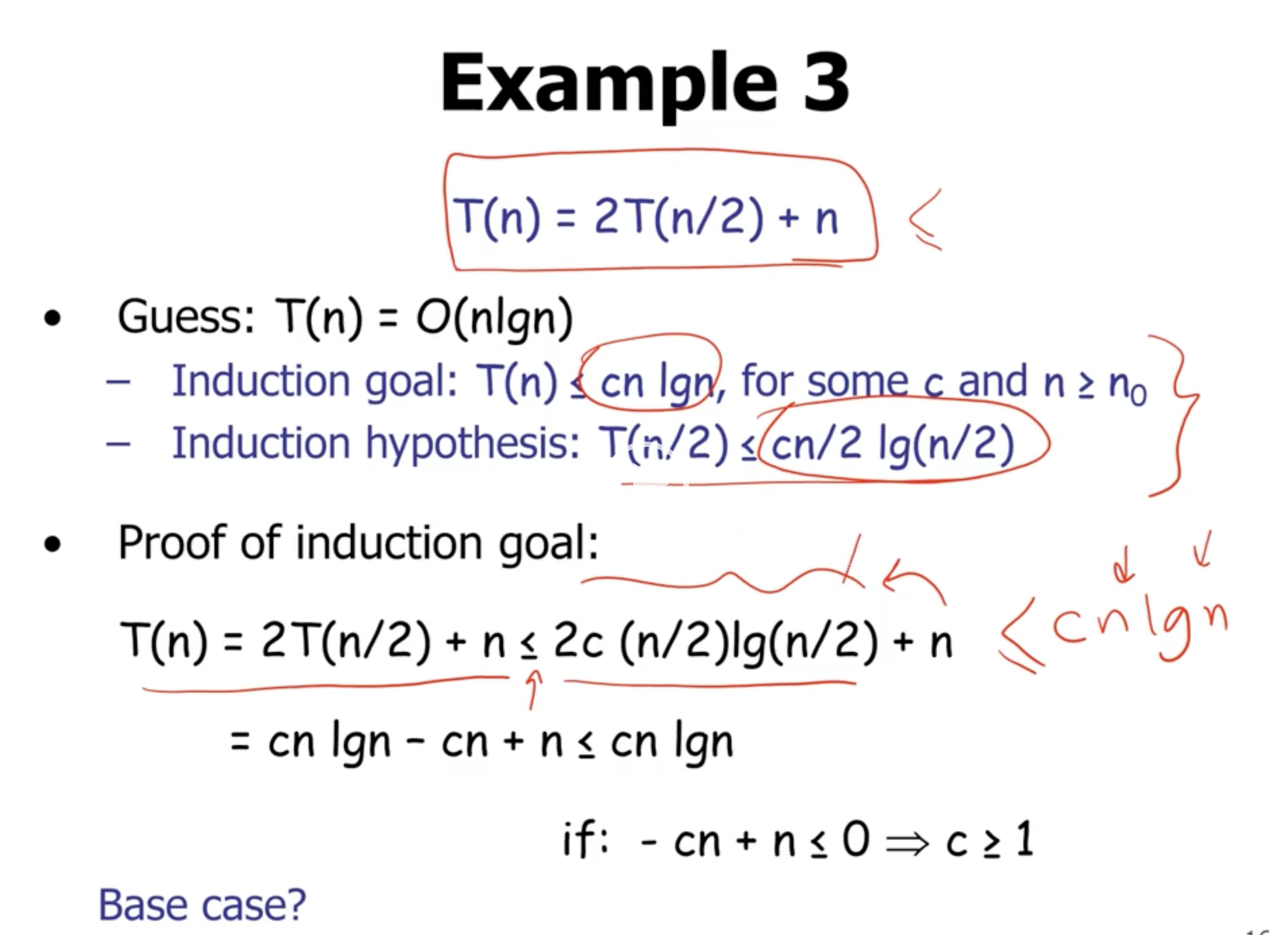

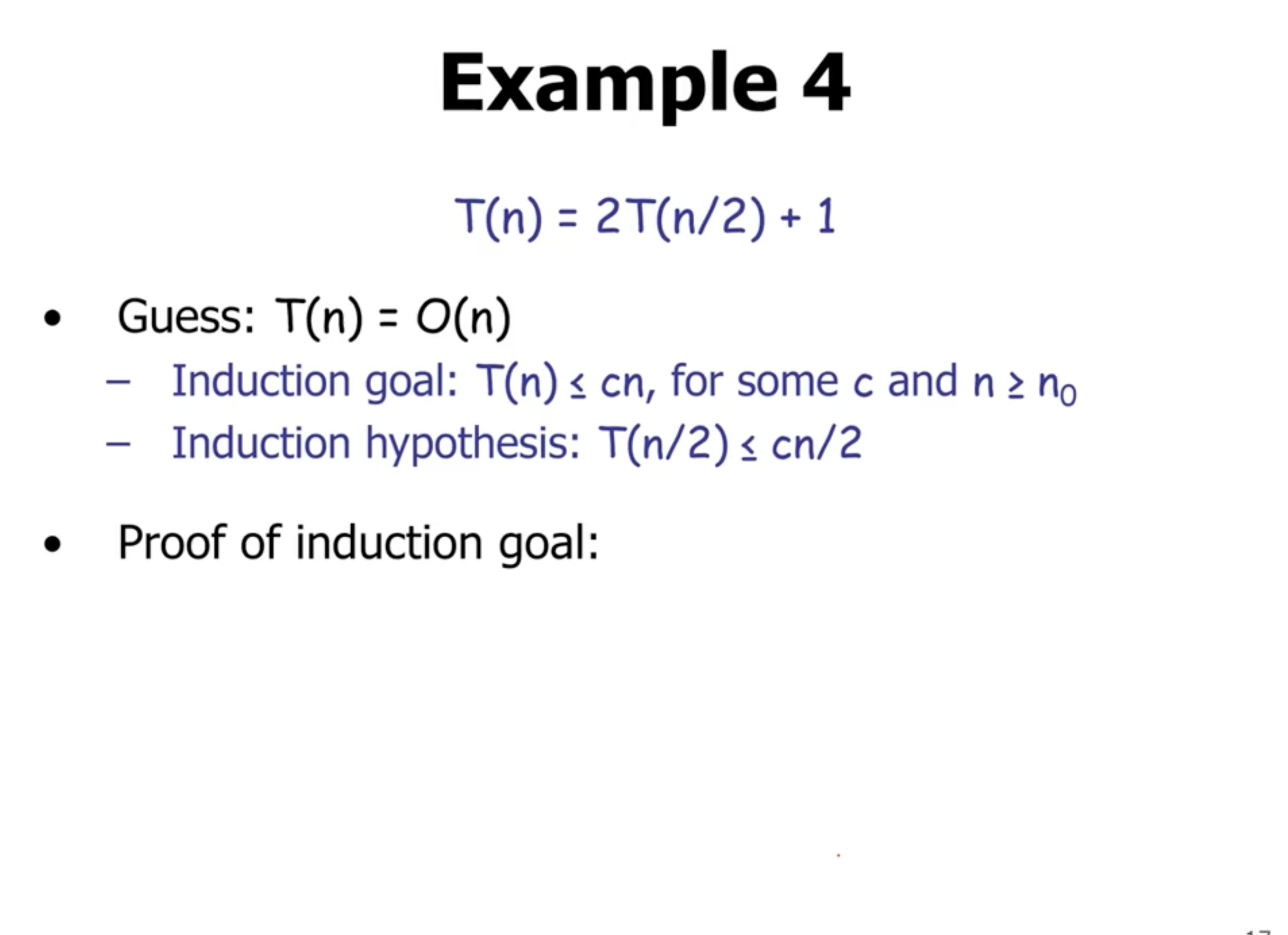

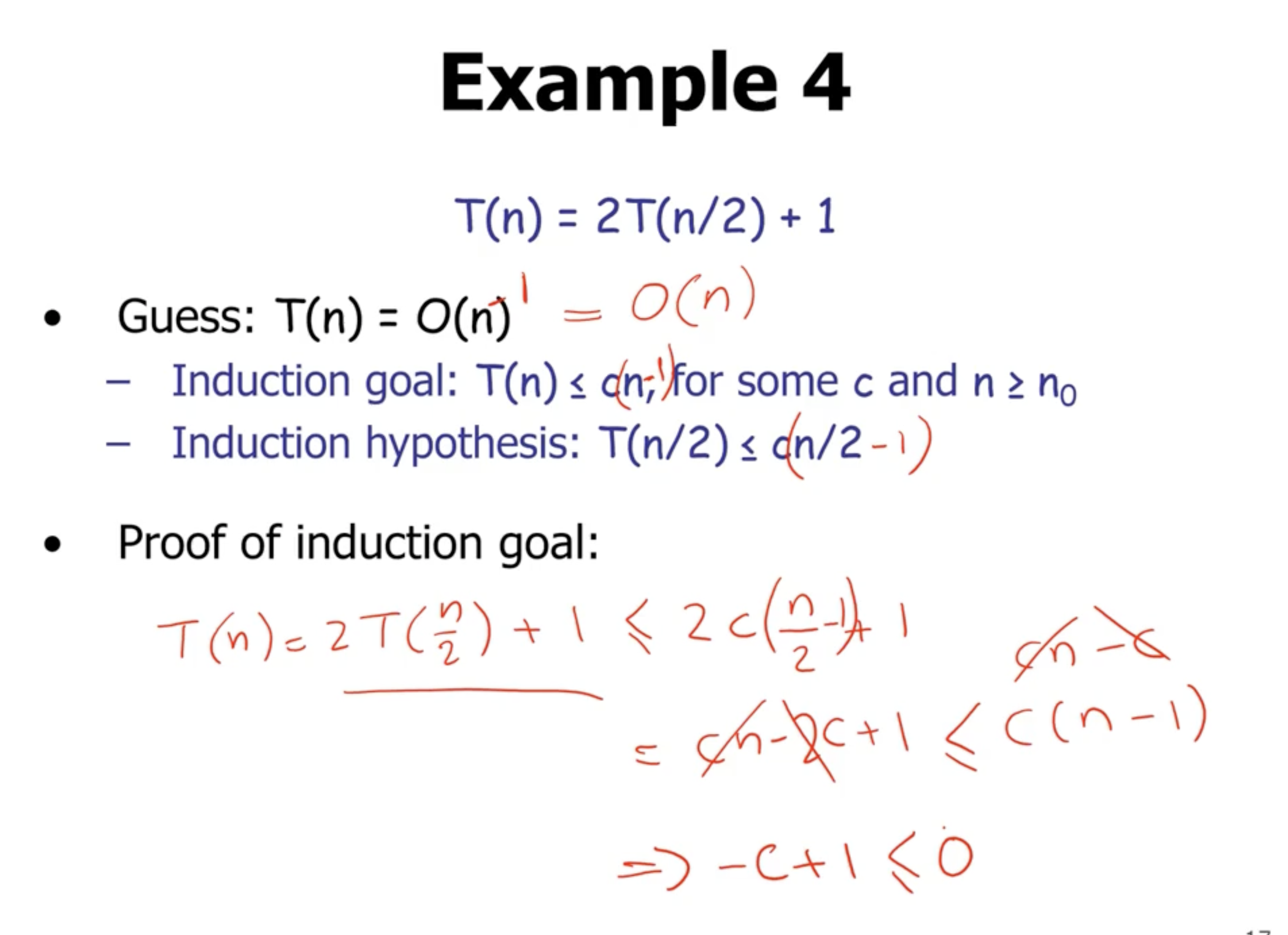

Substitution method #

- Guess a solution

- Use induction to prove that the solution works

If \( -d + c \leq 0, d \geq c \) .

If \( 2cn - c - n \geq 0 \)

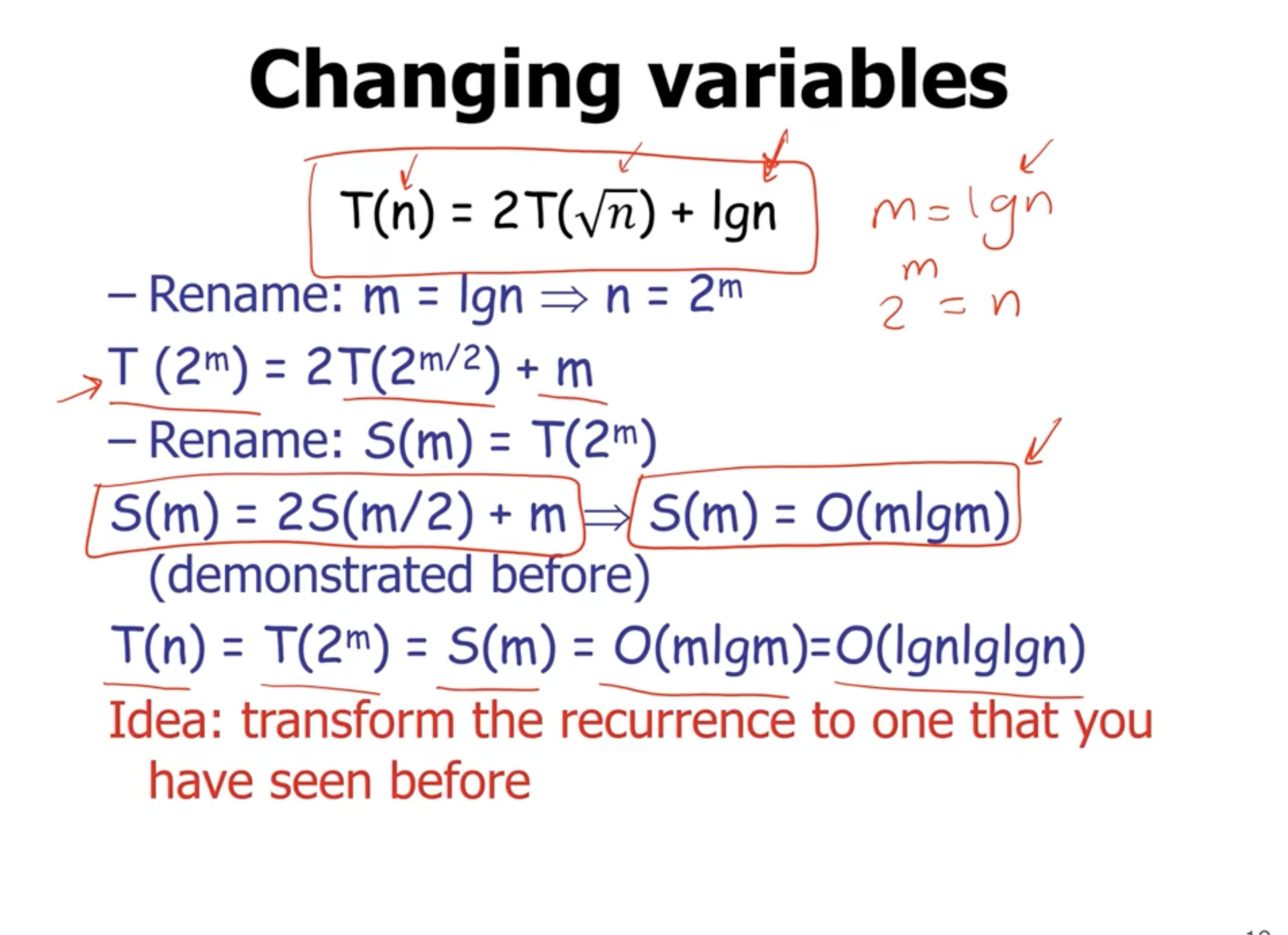

Changing variables #

Worse case analysis of quicksort #