Data programming #

File: Topics in C programming useful for cryptography

Count the number of even chars #

in C #

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdint.h>

int num_even(void * p, int nbytes)

{

uint32_t * p32 = (uint32_t *) p;

int nitems = nbytes / 4;

int acc = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < nitems; i++)

if (p32[i] % 2 == 0)

acc = acc + 1;

return acc;

}

int main()

{

uint8_t buf[] = {0xFF, 0x00, 0xFF, 0x00, 0xFF, 0x00, 0xFF, 0x00};

printf("%d\n", num_even(buf, 8));

return 0;

}

Depending on the endian, the output is either 0 or 2.

We can not depend on the endianness of the CPU by using a helper function to load in the bytes little endian always:

uint32_t load_uint32_little(void * p)

{

uint8_t * p8 = (uint8_t *) p;

// extract bytes

uint32_t a = p8[0];

uint32_t b = p8[1];

uint32_t c = p8[2];

uint32_t d = p8[3];

// reassmble

return (d << 24) | (c << 16) | (b << 8) | a;

}

Good compilers will optimize this on an x86 machine to

_load_uint32_little:

movl (%rdi), %eax

ret

So we can polish our num_even function to handle the different endianness of CPUs:

int num_even(void * p, int nbytes)

{

uint32_t * p32 = (uint32_t *) p;

int nitems = nbytes / 4;

int acc = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < nitems; i++)

{

uint32_t tmp = load_uint32_little(p32 + i);

if (tmp % 2 == 0)

acc = acc + 1;

}

return acc;

}

and now we get 0 for output both times.

in Java #

public class Lect2

{

static int load_uint32_little(byte[] p, int offset)

{

// extract bytes

int a = p[0 + offset];

int b = p[1 + offset];

int c = p[2 + offset];

int d = p[3 + offset];

// reassmble

return (d << 24) | (c << 16) | (b << 8) | a;

}

static int num_even(byte[] p)

{

int nitems = p.length / 4;

int acc = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < nitems; i++)

{

int tmp = load_uint32_little(p, i * 4);

if (tmp % 2 == 0)

acc = acc + 1;

}

return acc;

}

public static void main(String[] args)

{

byte[] buf = {-1, 0x00, -1, 0x00, -1, 0x00, -1, 0x00};

System.out.printf("%d\n", num_even(buf));

}

}

This can be done in a much nicer way using Java’s library, replacing the load_uint32_little method.

We can do this using ByteBuffer.

import java.nio.*; // for ByteBuffer

// no longer need the load_uint32_little method

static int num_even(byte[] p)

{

ByteBuffer bb = ByteBuffer.wrap(p);

bb.order(ByteOrder.LITTLE_ENDIAN);

IntBuffer ib = bb.asIntBuffer();

int nitems = p.length / 4;

int acc = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < nitems; i++)

{

int tmp = ib.get(i);

if (tmp % 2 == 0)

acc = acc + 1;

}

return acc;

}

Note: We need to change the endianness of ByteBuffer because in Java it defaults to big.

Big vs little endian #

If we’re loading

FF 00 FF 00 FF 00 FF 00

from memory, the byte are transferred from memory to a register.

If our register is 32 bits long, and we read using a big endian computer, our register will look like:

FF 00 FF 00 FF 00 FF 00

The bytes are read in from the big side first.

On a little endian computer, our register will look like this:

00 FF 00 FF 00 FF 00 FF

The bytes are read in from the little side first.

Rotation #

A lot of cryptography is built upon three operations:

- add

- xor

- rotate.

As long as you alternate between these 3 instructions, they will never compose. So they turn out to be a common building block for writing cryptographic functions.

Each of these 3 instructions has a single assembly instruction. Both add and xor are operators in C, but for rotate we have to write our own function. The compiler will recognize the rotate function and turn it into the assembly instruction.

Lets say we want to rotate this register to the left 4

before 1111 0000 1100 0011

rotl 4 0000 1100 0011 1111

We can piece this operation together using bitwise operations

rotl(x, n):

return (x << n) | (x >> (16 - n))

Data flow #

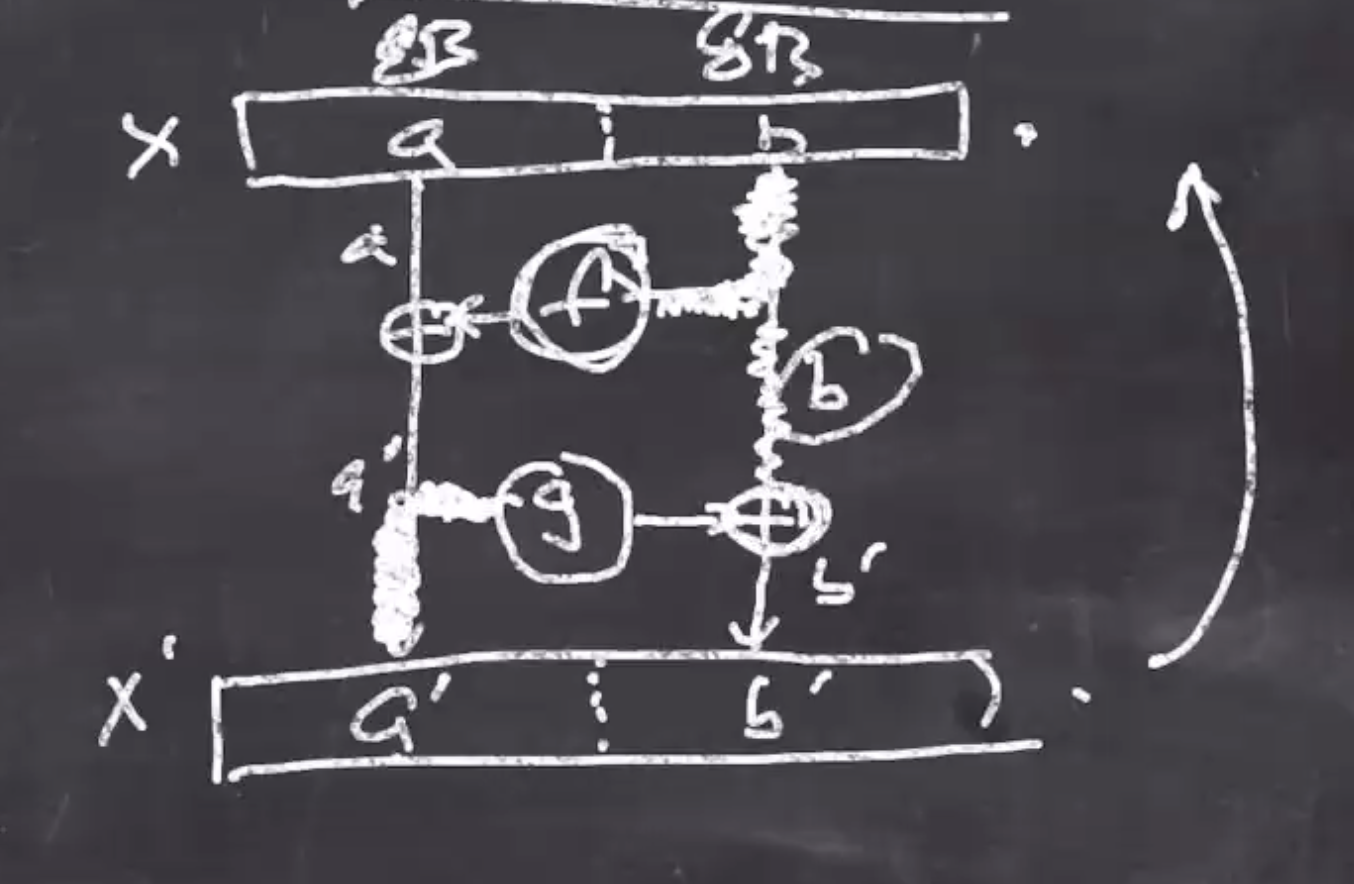

If we have an input to a Feistal function, it will be split in half and processed to an output.

If we have a 16 bit register, it is cut into two 8 byte pieces, \( a \) and \( b \)

sequenceDiagram participant a participant b b->>a: f Note left of a: a' = f(b) XOR a a->>b: g Note right of b: b' = g(a') XOR b

So the function \( f \) and \( g \) go from 8 bytes to 8 bytes.

So if we know \( a \) and \( b \) :

\( a' = f(b) \oplus a \\ b' = g(a') \oplus b\)We can also figure out the inverses

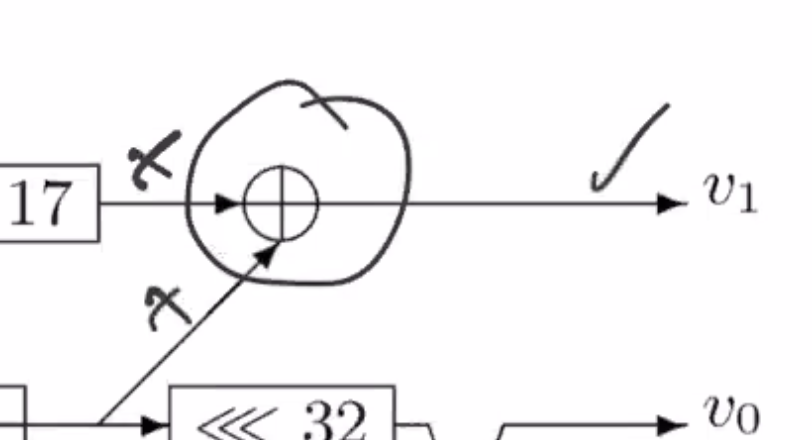

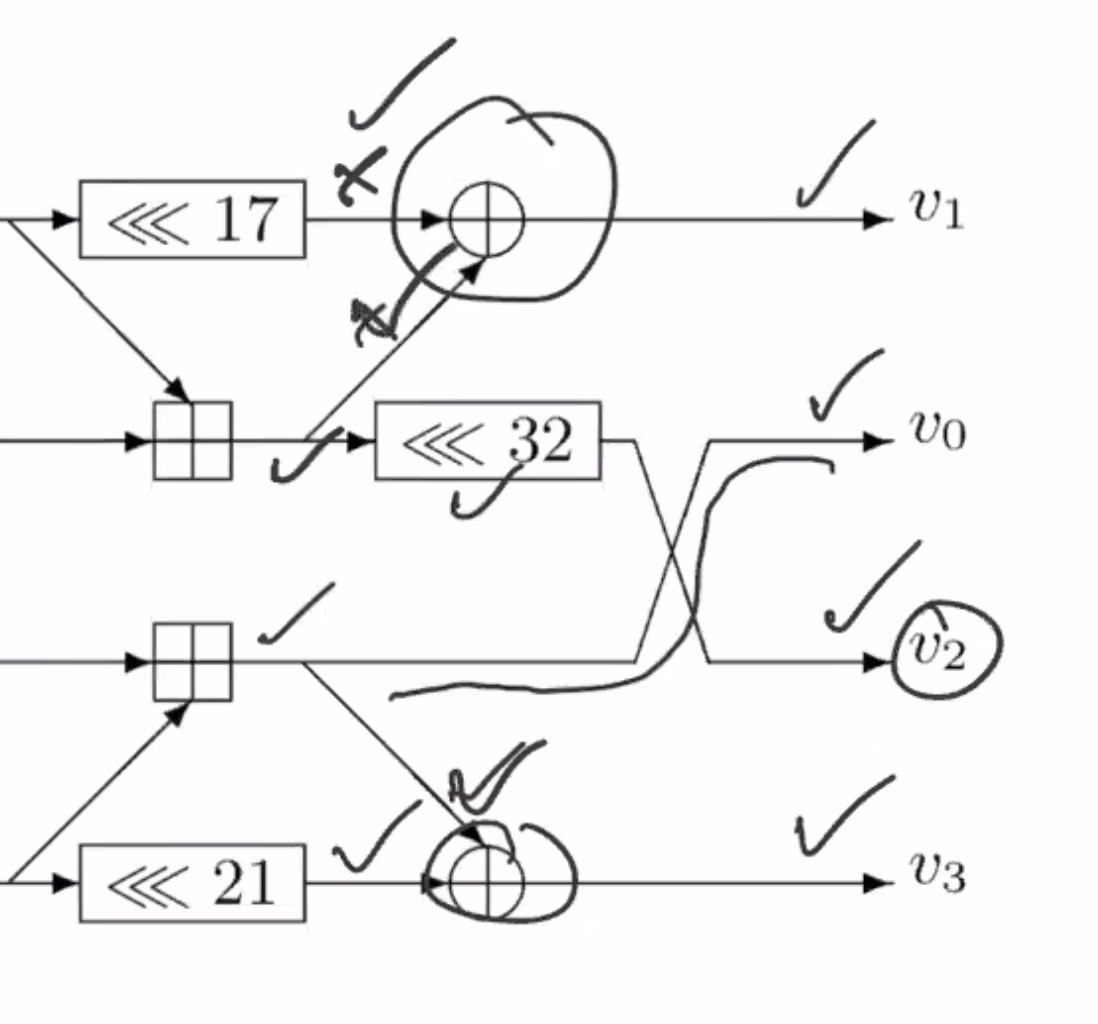

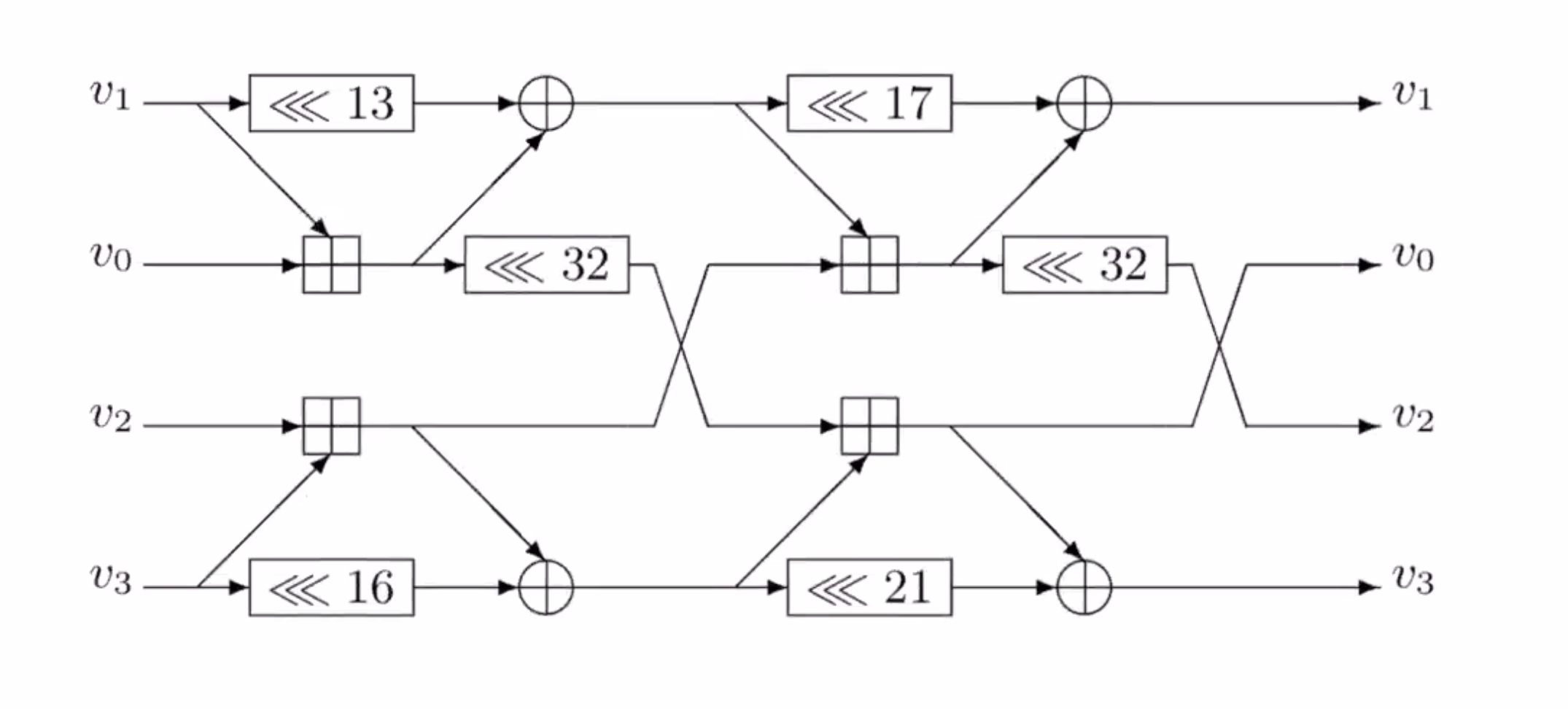

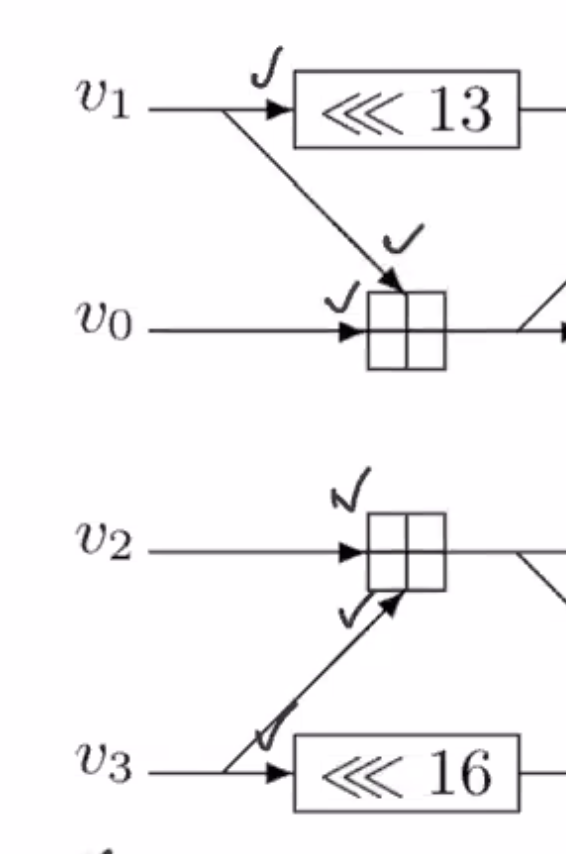

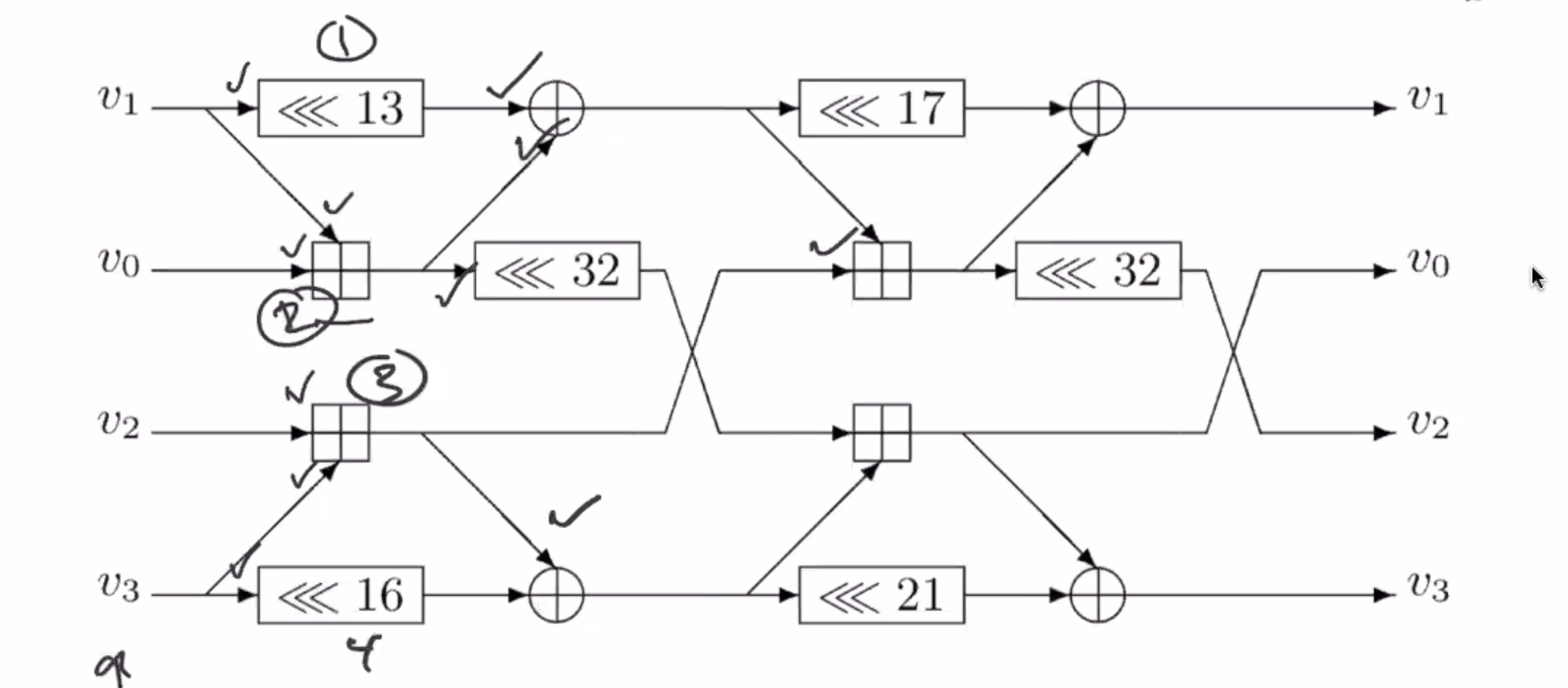

\( b = g(a') \oplus b' \\ a = f(b) \oplus a'\)SipHash diagram #

This is the flow diagram for SipHash.

\( v_0, v_1, v_2, v_3 \) are each 64 bits each.

To turn this into code, note all the areas where operations have known operators.

So the areas with check marks are known operations.

On the notation:

- \( <<< \) is rotate

- \( \oplus \) is xor

- \( \boxplus \) is add

So follow the flow of the diagram from left to right and whenever there is data ready to go, that can be implemented as a line of code. You have to find the combination of instructions to perform to get through the diagram.

Looking at this diagram, can we tell of this is an invertible function?

We could work from the output side towards the input side to see if its invertible (reverse the arrows).