Tweakable block ciphers #

The idea is that our block cipher \( E \) will take our key, and a second input called a tweak. \[\begin{aligned} \tilde{E}:(\text{key, tweak}) \to \left( \{0,1\}^b \to \{0,1\}^b \right) \end{aligned}\]

We notate that the block cipher is tweakable via the tilde notation, \( \tilde{E} \) .

The key must be random and private, but the tweak is non-random and public.

So why use a tweak?

- Changing a key is expensive

- Changing a tweak is cheap

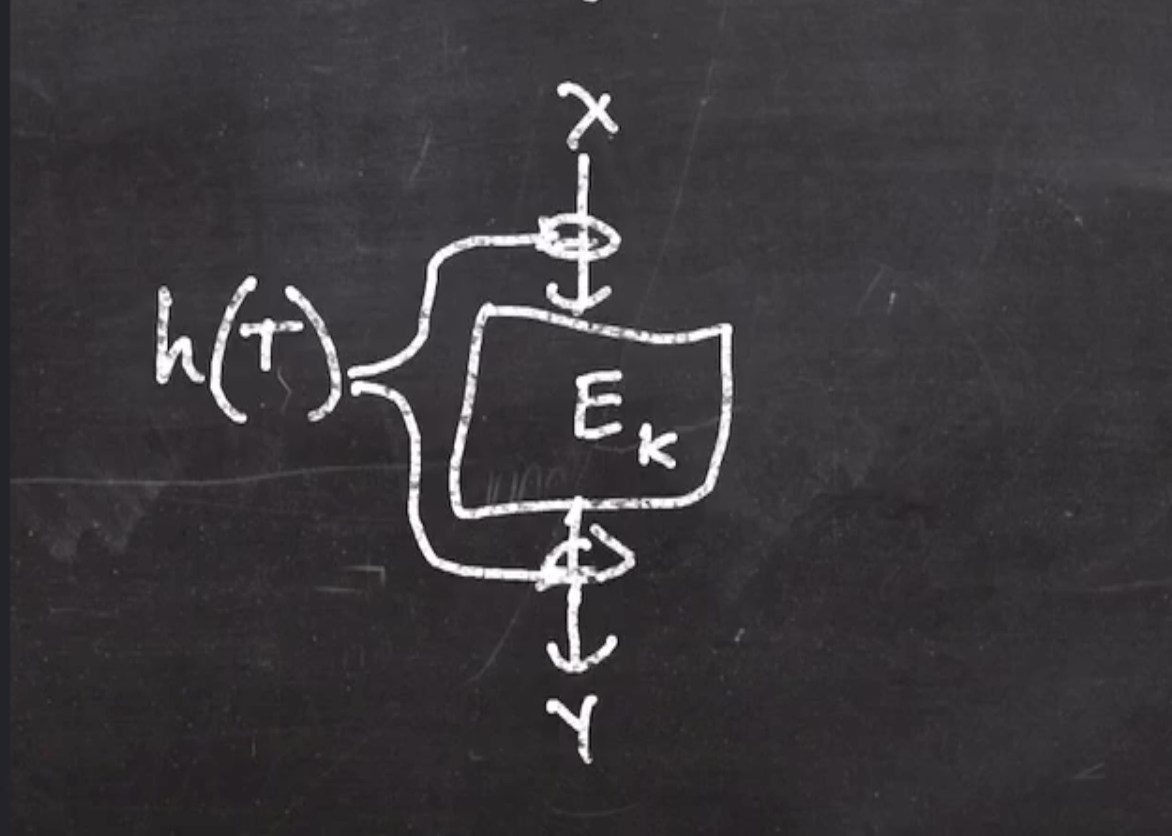

The layout of a tweakable block cipher may look like this:

- The tweak is hashed and xor’d before and after the block cipher. The hash function is an almost-universal hash function.

- Each time we change the tweak, different values are being xor’d before and after.

- Because a hash output is unpredictable, since the adversary doesn’t know the hash function or key, the adversary doesn’t know what is going into the block cipher.

Read more about tweakable block ciphers

OCB – Authenticated Encryption #

Note: This is a project that the Professor worked on.

A form of authenticated encryption. The block cipher here can be thought of as a tweakable block cipher.

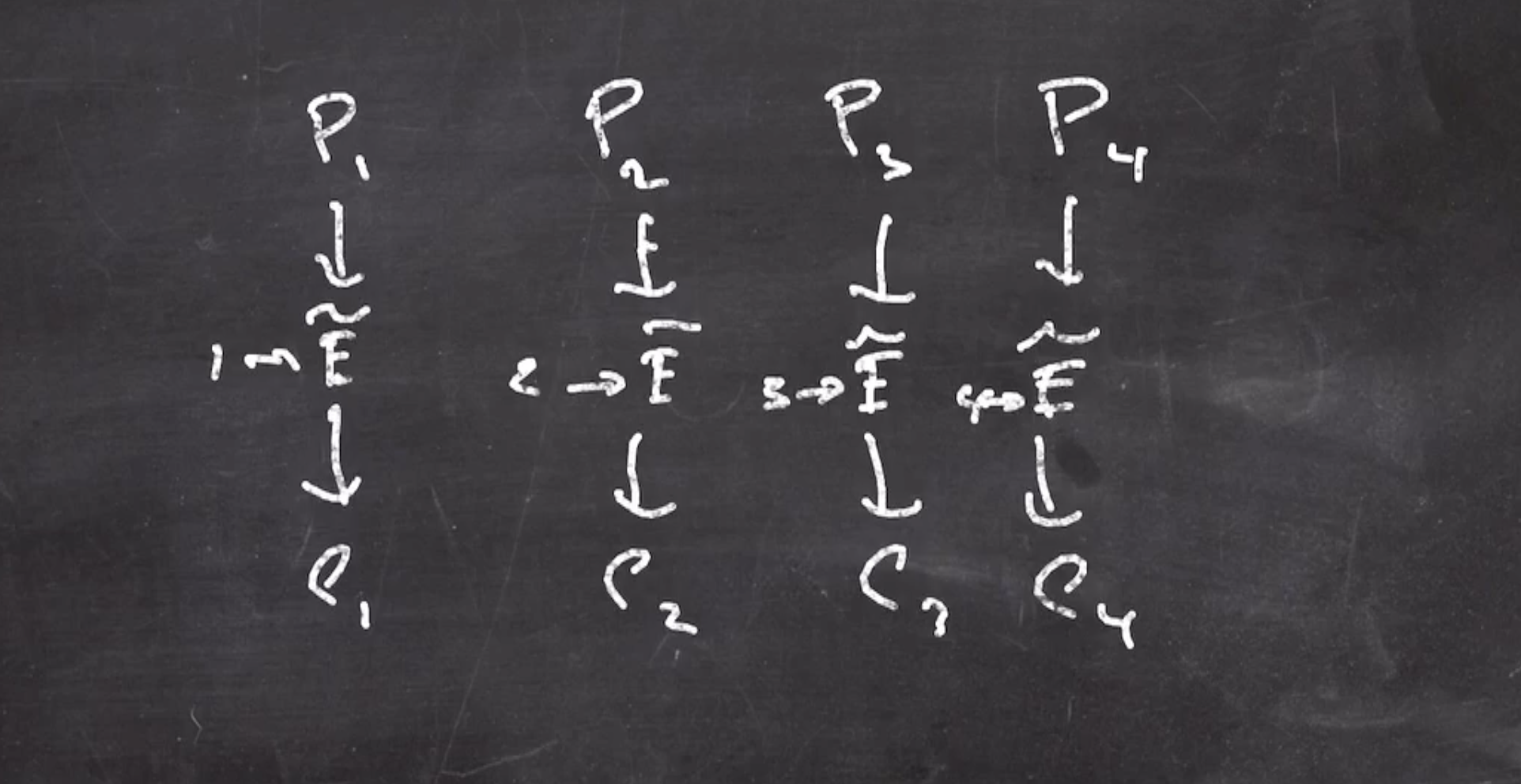

The layout is as follows:

- plaintext is broken into blocks

- each block is fed through the tweakable block cipher, each block cipher’s tweak is incremented from the last

- the cipher text is the output blocks concatenated back together

Since we are using a different tweak each time, we can think of each column as an independent random permutation (each used one). So, all the cipher text blocks are uniform. Because of this, the advantage an adversary has to distinguish ciphertext from random is 0.

So where does the authentication come in?

To create the tag:

- Xor all plaintext blocks together, and send through \( \tilde{E} \) , with a tweak of 0 (something that hasn’t been used before). \[\begin{aligned} \text{tag} = \tilde{E}(P_1 \oplus P_2 \oplus \cdots \oplus P_i) \end{aligned}\]

- This is really cheap!

To authenticate:

- Decrypt the ciphertext into its plaintext blocks, then xor plaintext blocks and send through the tweakable block cipher.

Optimizing sequential hashes #

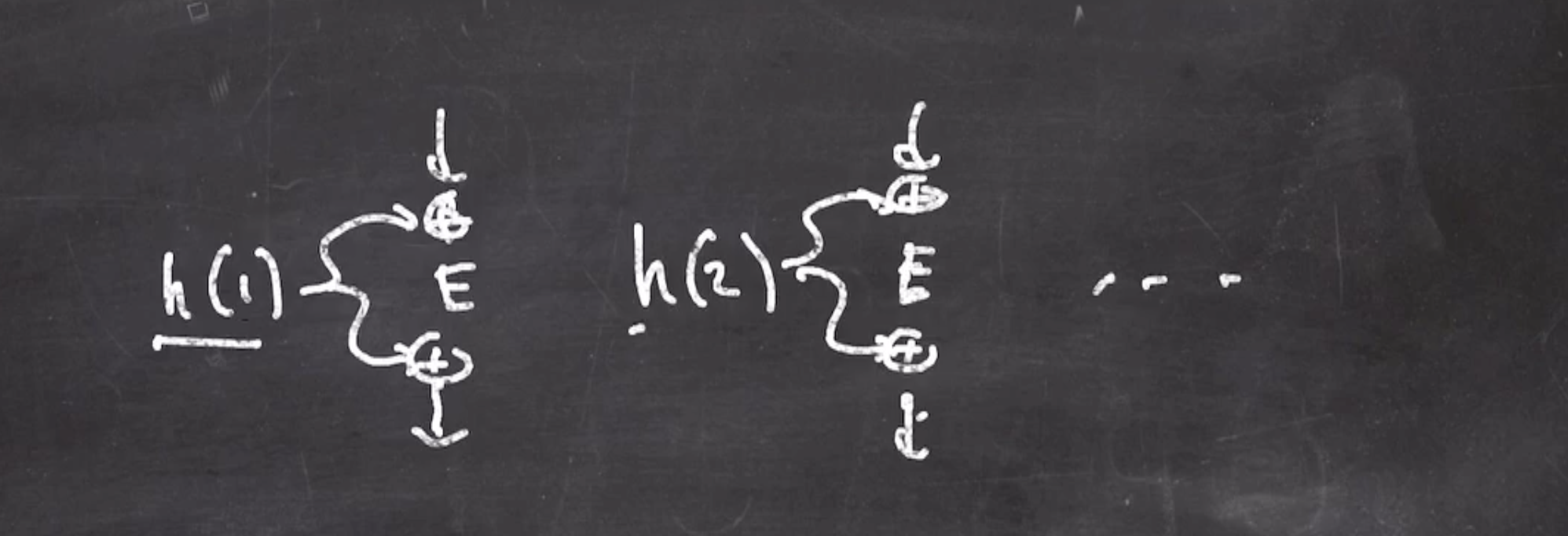

Since we are using a hash of an incrementing counter, we can optimize the process.

Can we go from the hash of the first tweak to the hash of the second tweak more efficiently than recalculating?

- If we start off with an intial value \( h_\text{iv} \) , we can define the currently hashed tweak as \[\begin{aligned} h_\text{iv}(t) = (\text{iv}) \cdot 2^t \end{aligned}\] This works especially well in \( GF(2^b) \) .

- The next hash is defined as can be reached by doubling the last value again \[\begin{aligned} h_\text{iv}(t + 1) = (\text{iv}) \cdot 2^{t + 1} \end{aligned}\] Some pseudo to get the next hash

next_hash(x):

if high bit of x == 1:

x = (x << 1) xor 135 // raise degree of all terms and xor

else

x = x << 1

Note: We xor by 135 because that is the same bit pattern as the modulus.

Certificates #

Recall that public key (asymmetric) cryptography means that each party has a public key and a private key. This means that the number of keys needed is to the order of \( O(n) \) (whereas symmetric key cryptography needs \( O(n^2) \) keys.)

We use a hybrid of the 2 types to get the benefits of each.

- Establish a key with asymmetric cryptography,

- Solves the key problem

- Switch over to symmetric cryptography

- Symmetric is faster

So certificates answer the question “how do you make everyone’s public key available?”

A certificate is a text file with

- The owner of the certificate: name, company, other identifiers to who owns the certificate

- Who issued the certificate: certificate issuer’s id

- Usage information: valid date range

- Valid uses: certificates only have certain permissions

- Owner’s public key

- Issuer’s signature: all of the previous fields are hashed to create the signature

The goal of the certificate is to associate the owner with their public key.

If Alice wants to send Bob a file, and Bob wants to trust that the file is correct:

- Alice sends a file, signature (of file), and Alice’s certificate

- Bob uses Alice’s public key to verify the signature of the file

Note: While there are long living trusted certificates (distributed with operating systems), most certificates are sent with the data.

So why should Bob trust Alice’s certificate? In an adversarial environment, Bob should not trust it. Bob should check the issuer on Alice’s certificate to see if it is issued by a trusted certificate authority (CA).

To certify:

- Receive \( A \) ’s certificate, signed by \( B \)

- Look for \( B \) ’s certificate in the trusted bundle, if its there we trust it

- If we receive multiple certificates at once: \( A,B,C \) is a chain of trust

- Follow the chain of trust until we see a certificate that is in the trusted bundle

Certificate authorities are certificates that are from trusted companies, or the government. They issue their own certificates to operating systems and brownser manufacturers.

Tools to look at certificates #

We can use OpenSSL to look at certificates for websites, ie

openssl s_client -connect www.amazon.com:443

Note: If we run the command with the --showcerts flag, it shows the entire chain of trust.

which gives us this

-----BEGIN CERTIFICATE-----

MIIHoTCCBomgAwIBAgIQBgFdj+Nrd6vfZrmQSH7aQDANBgkqhkiG9w0BAQsFADBE

MQswCQYDVQQGEwJVUzEVMBMGA1UEChMMRGlnaUNlcnQgSW5jMR4wHAYDVQQDExVE

aWdpQ2VydCBHbG9iYWwgQ0EgRzIwHhcNMjEwNDE5MDAwMDAwWhcNMjIwNDExMjM1

...

YlgYDFLnfNahdqfgLTLRyv06bOKVc1V6axvvZSs4F9i1FXtYtBe6IhZrS04zYL60

He5cSbVV4DSZAzvlc9P8d5LZSOYMV6oMyGBqb6wCpH2Mju/I0gLM8OcDN/v2eGkz

s3KLTGnom5QuAnMw7rt/l+9Gr+y1EA3srdVH0de4vG/sO6gRGg==

-----END CERTIFICATE-----

Note: Part of the certificate ommited here for brevity.

We can parse this using another command

openssl x509 -noout -text

which parses from stdin, so we can paste in our certificate and we get information like

Version: 3 (0x2)

Serial Number:

06:01:5d:8f:e3:6b:77:ab:df:66:b9:90:48:7e:da:40

Signature Algorithm: sha256WithRSAEncryption

Issuer: C = US, O = DigiCert Inc, CN = DigiCert Global CA G2

Validity

Not Before: Apr 19 00:00:00 2021 GMT

Not After : Apr 11 23:59:59 2022 GMT

Subject: CN = www.amazon.com

Along with this information, it also gives us

- The owner’s public key

- Information about the usages, permissions

- A list of alternative names that this certificate also signs

- Actual signature of all prior data

So what does the actual trusted bundle (the distributed trusted certificates in operating systems) look like?

The file cacert.pem here shows us the trusted certificates.