How are permutations made? #

To create a permutation we will

- Compose simple steps, each with a different mathematical structure, providing confusion and diffusion.

- we can use add, because it is in \( Z_{2^{32}} \)

- xor, because it is in \( Z_{2} \)

- and rotate, because it is non-linear (not represented by a linear equation)

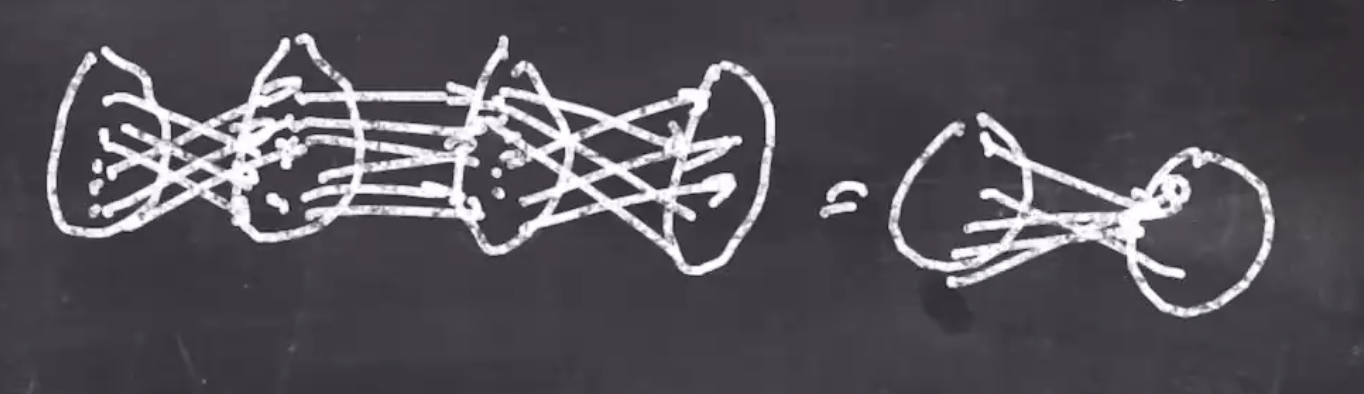

Adding on its own makes a predictable structure, but if we xor after and then rotate we can get a much more confusing structure. By composing these 3 instructions, we can achieve confusion and diffusion.

The composition of multiple instructions can make the output look a lot more random.

Confusion #

An operation has confusion if it has a complex input-output behavior. Hard to model mathmatically and looks somewhat random.

Some cryptanalysis can try to approximate the function using a mathematical function. So the more confusion that a function has, the harder it is to approximate.

Diffusion #

An operation has diffusion if changing an input bit changes output bits in other locations.

For example, if

0101 -> f -> 1111

0111 -> f -> 1001

Changing 1 input bit caused 2 output bits to change.

The diffusion of the simple operations:

add

x = 5 0101

1 0001

x + 1 0110 // 2 bits changed, little diffusion

When using add, carry bits provide a little diffusion.

xor

x = 0 0000

5 0101

x ^ 5 0101 // no diffusion

No diffusion is provided using xor.

rotate

x = 3 0011

x rotl 2 1100 // good diffusion!

x = 2 0010

x rotl 2 1000 // however not a huge change in

// diffusion between different values

Note: Using rotate on different values doesn’t have a huge relative diffusion, however good diffusion can be achieve when changing the input if you also change the rotation amount.

Ideally, if we change 1 bit in our input, we’d like at least half of the output bits to change.

Add/rotate have a little local diffusion. Local diffusion refers to the word being altered.

The characteristics of an algorithm #

Asymmetric cryptoalgorithm #

Usually has

- Composed simple steps, provides local confusion and diffusion

- Rearrangement of parts of the data, to spread the confusion and diffusion

- Loop many times to amplify the confusion and diffusion

perm384

#

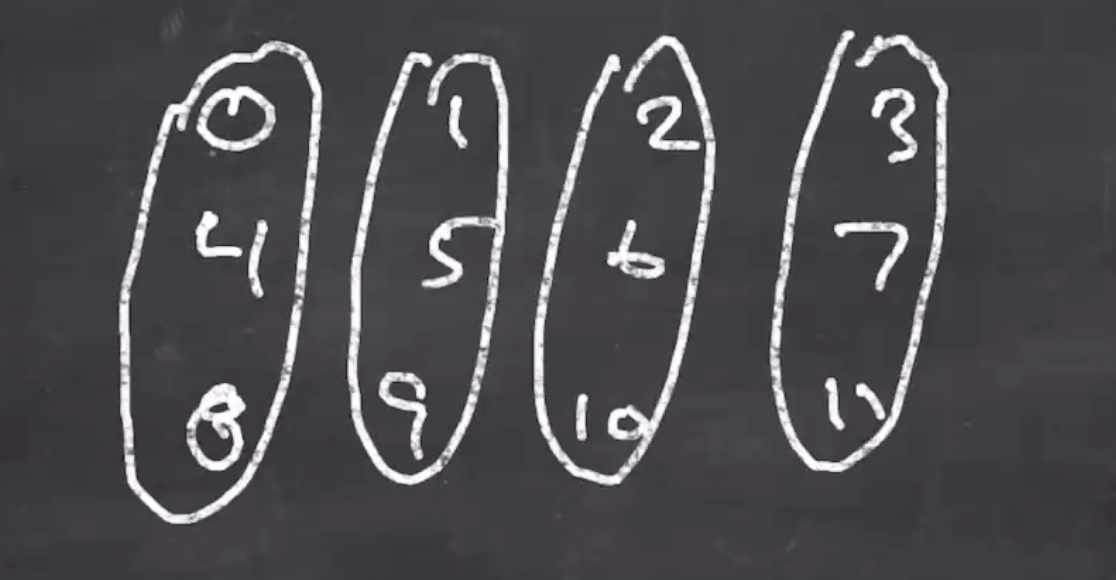

A permutation that scrambles 384 bits. Since its a permutation, its both 1-to-1 and onto, so every 384 bit string maps to another 384 bit string.

It takes 48 bytes, and scrambles them over 24 iterations (which we call rounds).

Heres the pseudo:

perm384(p):

for round = 0 to 23

scramble(p32+0, p32+4, p32+8)

scramble(p32+1, p32+5, p32+9)

scramble(p32+2, p32+6, p32+10)

scramble(p32+3, p32+7, p32+11)

if (round mod 4 == 0) // ie, when round is 0, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20

swap uint32_t values at p32+0 and p32+1

swap uint32_t values at p32+2 and p32+3

xor uint32_t value at p32+0 with (0x79379E00 xor round)

if (round mod 4 == 2) // ie, when round is 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, 22

swap uint32_t values at p32+0 and p32+2

swap uint32_t values at p32+1 and p32+3

Lets visualize the first 4 scrambles:

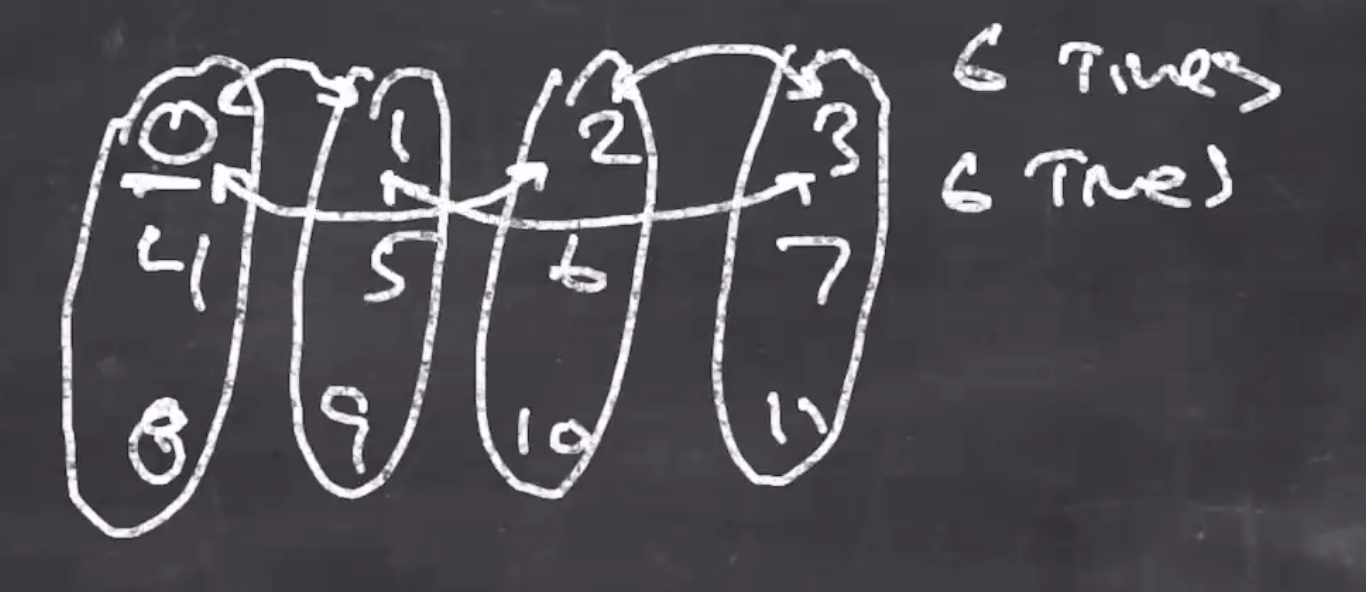

Since we are working with 48 bytes, we have 12 uint32s. This gives us good diffusion among the 3 being scrambled. (If we change a bit in 0, it will change bits in 4 and 8, but nowhere else.) This is the reason why we swap and rotate every once in a while.

This creates a lot more diffusion throughout the 48 bytes. When 0 and 1 are swapped, it propagates and also affects 4,5,8,9.

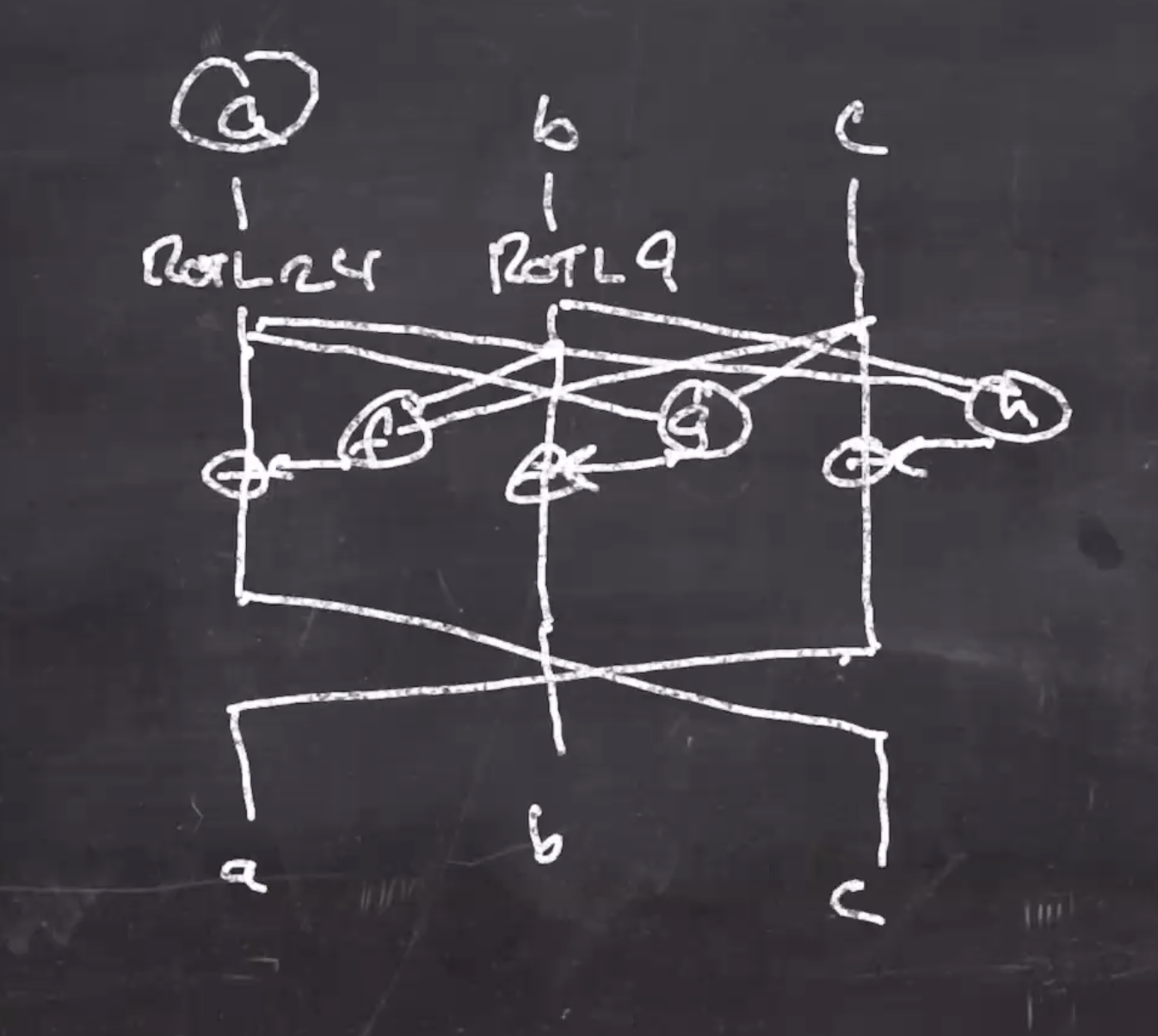

scramble

#

Heres the pseudo for scramble:

scramble(a, b, c):

x = ROTL(a, 24)

y = ROTL(b, 9)

z = c

a = z xor y xor ((x and y) << 3)

b = y xor x xor ((x or z) << 1)

c = x xor (z << 1) xor ((y and z) << 2)

Heres a diagram of scramble where

\( f,g,h \)

are 3-4 bitwise operators:

Analyzing perm384

#

It ends up that perm384 very closely resembles a random function.

Due to Kerckoff’s law, we need to assume that everyone knows the algorithm that perm384 uses.

We want Alice and Bob to be able to send messages back and forth, without Eve extracting any information (or tamper with it).

So how do we do this if everyone knows the details of perm384?

We can answer this question using distinguishing games.

Lets demonstrate that perm384 by itself, is not usable as a random function.

So if we have a black box \( f \) , with

- the first world being

perm384 - the second world being a function

\( g: \{0,1\}^{384} \to \{0,1\}^{384} \)

(a random function with with the same signature as

perm384).

So our algorithm would be:

y = f(<0>_384)

x = perm384(<0>_384)

if x == y:

output "perm384"

else:

output "random permutation"

Note on notation:\[\begin{aligned} \text{advantage} &= P(\text{ guess perm384 } \mid \text{ is perm384 }) - P(\text{ guess perm384 } \mid \text{ is } g) \\ &= 1 - \frac{1}{2^{384}} \\ &\approx 1 \end{aligned}\]<0>_384means 0 represented in 384 bits.<x>_nmeansxrepresented innbits.

With an advantage of effectively 1, the distinguisher wins.

So perm384 is not a good permutation for encryption on its own.

So how do we do better?

Lets choose 2 new worlds and this time we’ll use a key \( k \) :

- world 1:

- let \( k \) be a random 256 bits

- \( f(x) = \text{perm 384}(x \oplus ( k || <0>_{128})) \)

- world 2:

- same as previous

Note on notation: The two vertical bars \(||\) indicate concatenation.

So our algorithm is

y0 = perm384(<0>_384)

y1 = perm384(<1>_384)

x0 = f^-1(y0)

x1 = f^-1(y1)

if (x0 xor x1) == <1>_384:

output "perm384"

else:

output "random permutation"

Note: This is only possible if \(f^{-1}\) is available.

This attack only works in a “chosen ciphertext model”, meaning we have the inverse function available.

In this construction

\[\begin{aligned} \text{advantage} \approx 1 \end{aligned}\]One last time:

If we have 2 worlds

- world 1

- let \( k \) be a random 256 bits

- \( f(x) = (k || <0>_{128}) \oplus \text{ perm384 }(x \oplus (k || <0>_{128})) \)

- world 2

- same as previous

So we’re xoring the output with the key \( k \) to protect the inverse.

In this construction

\[\begin{aligned} \text{advantage} \approx 0 \end{aligned}\]