Block cipher encryption mode examples #

For these examples, consider

- \( E: \{0,1\}^6 \to \{0,1\}^6 \)

- \( E(x) = \text{ROTL } (x,2) \)

- If needed

- \( \text{nonce} = 101 \)

- \( \text{IV} = 110111 \)

- Counters start at

<1> 10*padding

Encrypt the following

0000 1111 0000 1111

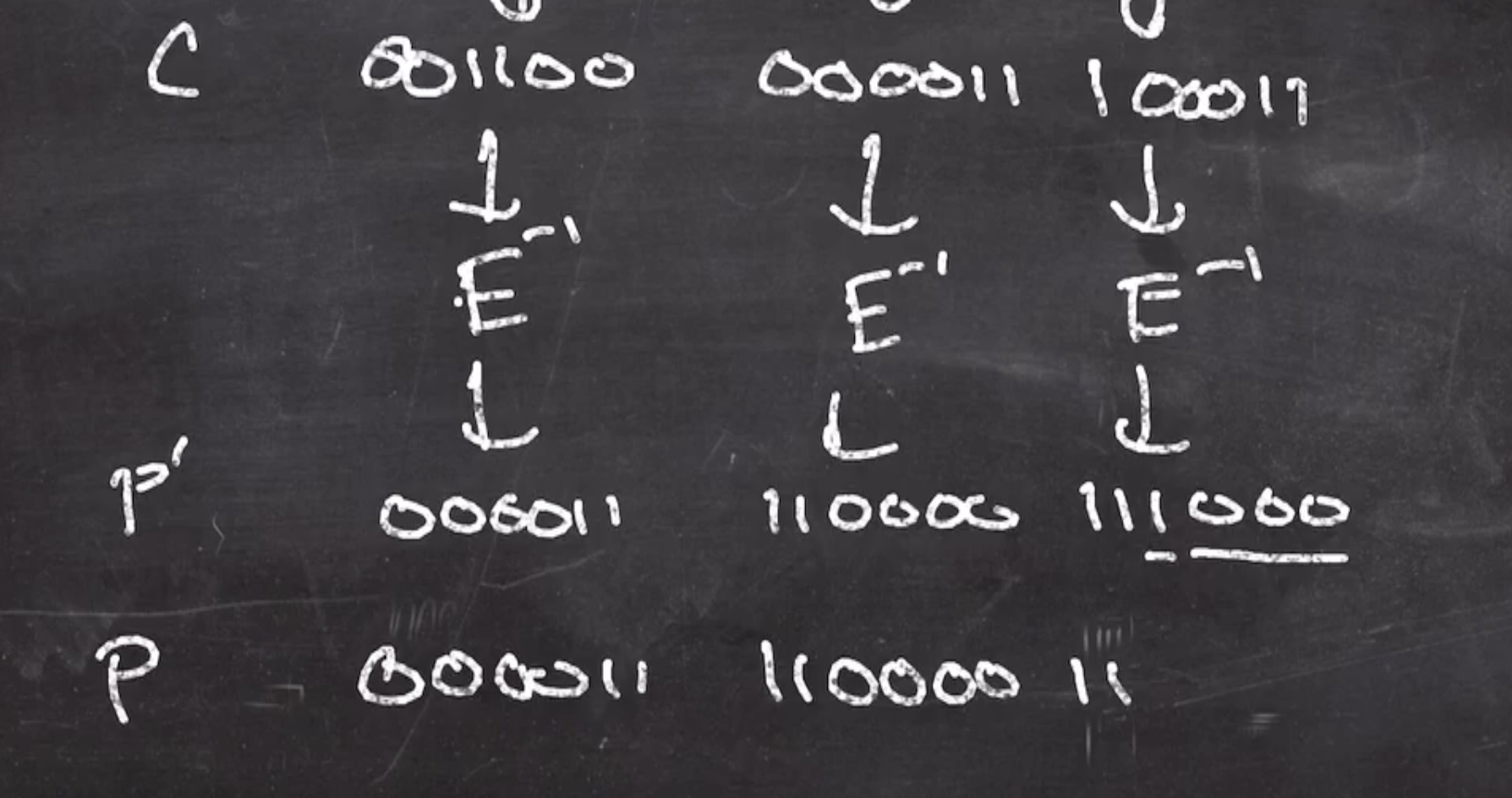

ECB #

Since we are using block sizes of 6 bits, we are encrypting

plaintext

000011 110000 11

So the first thing we have to do is pad the rightmost block.

padded plaintext

000011 110000 111000

Then we can send each block through \( E \)

ciphertext

001100 000011 100011

To decrypt, we have to use the inverse of \( E \) , ie rotate right by 2, then we depad

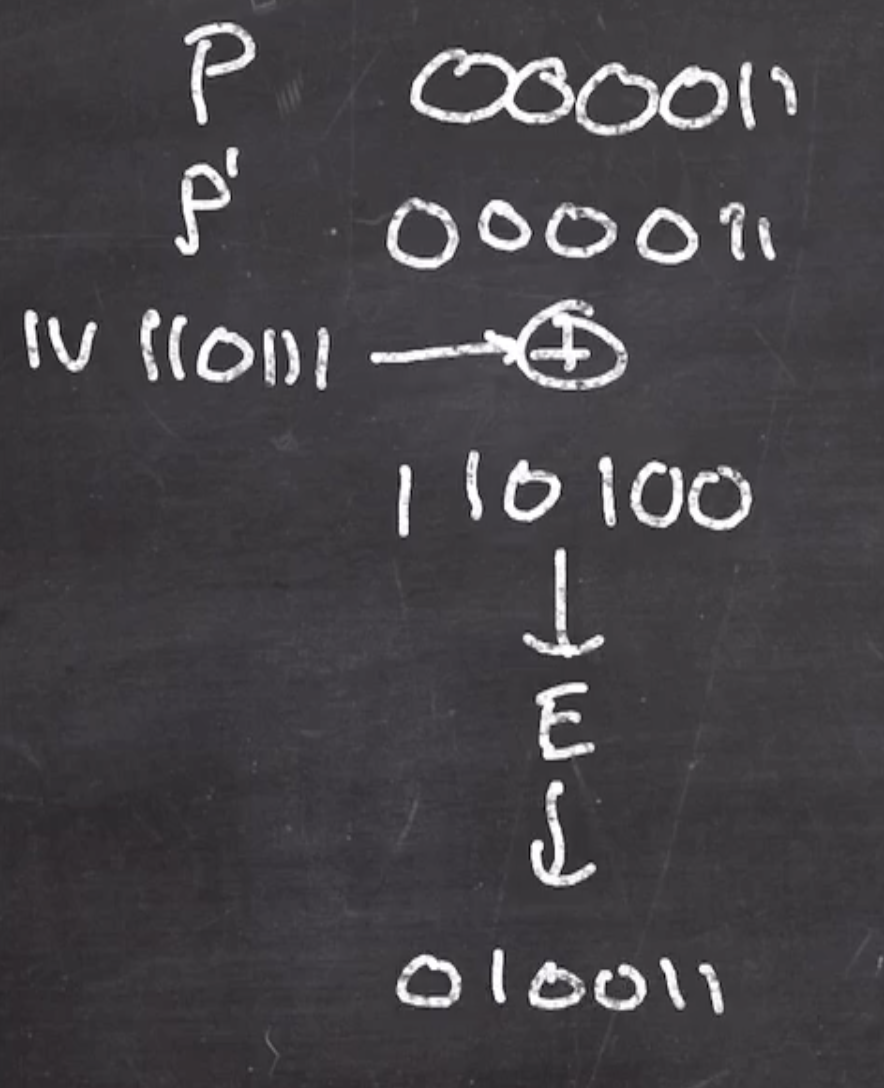

CBC #

We also need to pad our plaintext for CBC mode, so

plaintext

000011 110000 11

padded plaintext

000011 110000 111000

We will use \( IV = 110111 \)

So the first operation is to xor the first padded plaintext with the \( IV \) , then put through \( E \) ,

That value is now the new xor for the next block, and the process continues

Note when doing these types of problems on a quiz: Any error when calculating these xors will propagate through the rest of the ciphertext.

This gives us the ciphertext

ciphertext

010011 001110 011011

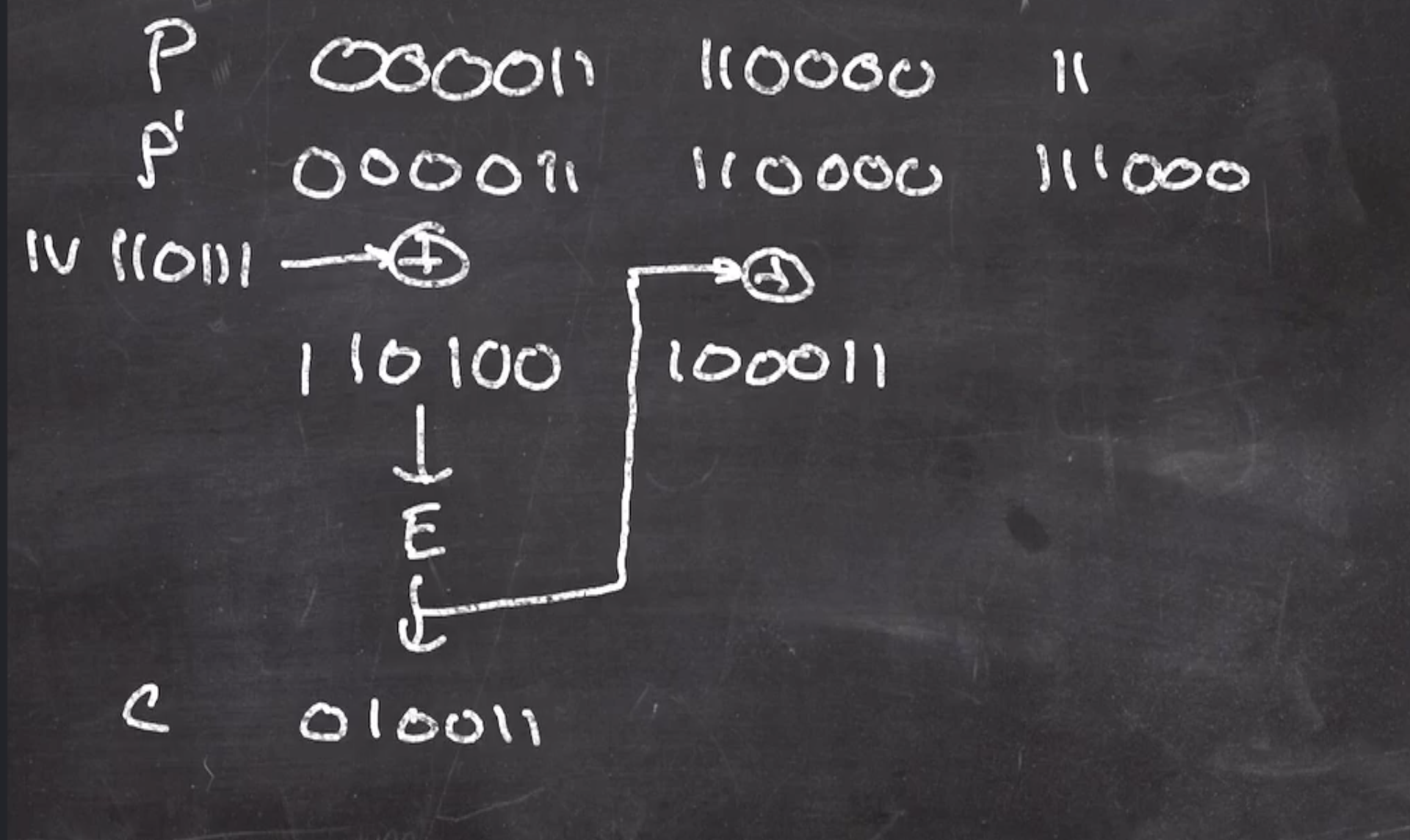

For decryption:

- We would receive the ciphertext, and

- The previous given variables/functions

We can reverse the arrows in our diagram to visualize it,

Note: The arrows from block \( n - 1 \) that is xor’d with block \( n \)’s arrow is not inverted. The reason is because xor is its own inverse.

Also, note that

- \( E^{-1} = \text{ROTR } (x, 2) \) , and

- We still need to know \( IV \)

We can start with the first block

and continue the process

Finally, we unpad by

- Strippping trailing zeros, and

- strip rightmost one

Note on CBC: While encryption is done serially, decryption can be done in parallel. Some hardware allows for multiple invocations of the permutation at the same time.

CTR #

Recall that counter mode is a stream cipher. It generates a stream of bits that is xor’d with the plaintext to obtain cipher (and opposite for decrypt).

It does not need padding. The goal is to produce at least as many bits as the message to be encrypted. So we will generate 3 CTR blocks to be enough for our message length of 18 bits

Our \( \text{nonce} = 101 \) , and our counter starts at 1.

So our 3 blocks look like this, where each block is the nonce concatenated with the counter:

101001 101010 101011

Every single block will be a different value, but we must never repeat a nonce for 2 different plaintexts.

We can then put our blocks through \( E \)

to produce our key stream. Then we xor our key stream with our plaintext

\[\begin{aligned} \text{ciphertext} = \text{plaintext } \oplus \text{ key stream} \end{aligned}\]

but we only use the amount of bits we need out of the key stream.

Note: When we send a message using CTR mode, we send both the nonce and the ciphertext.

Decryption:

\[\begin{aligned} \text{plaintext} = \text{ciphertext } \oplus \text{ key stream} \end{aligned}\]A benefit to CTR is that decryption uses the same process as encryption. Generate the keystream again using the same process, then xor the ciphertext to obtain the plaintext.

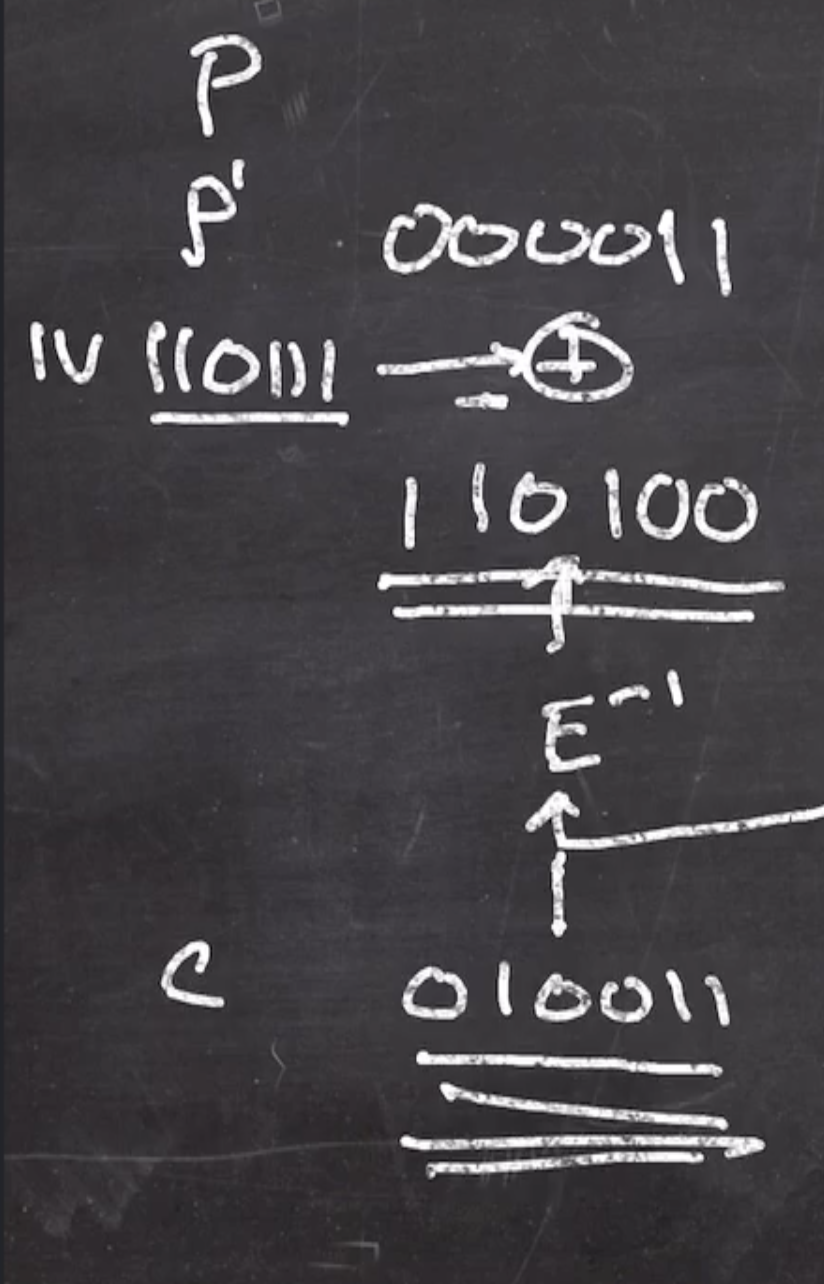

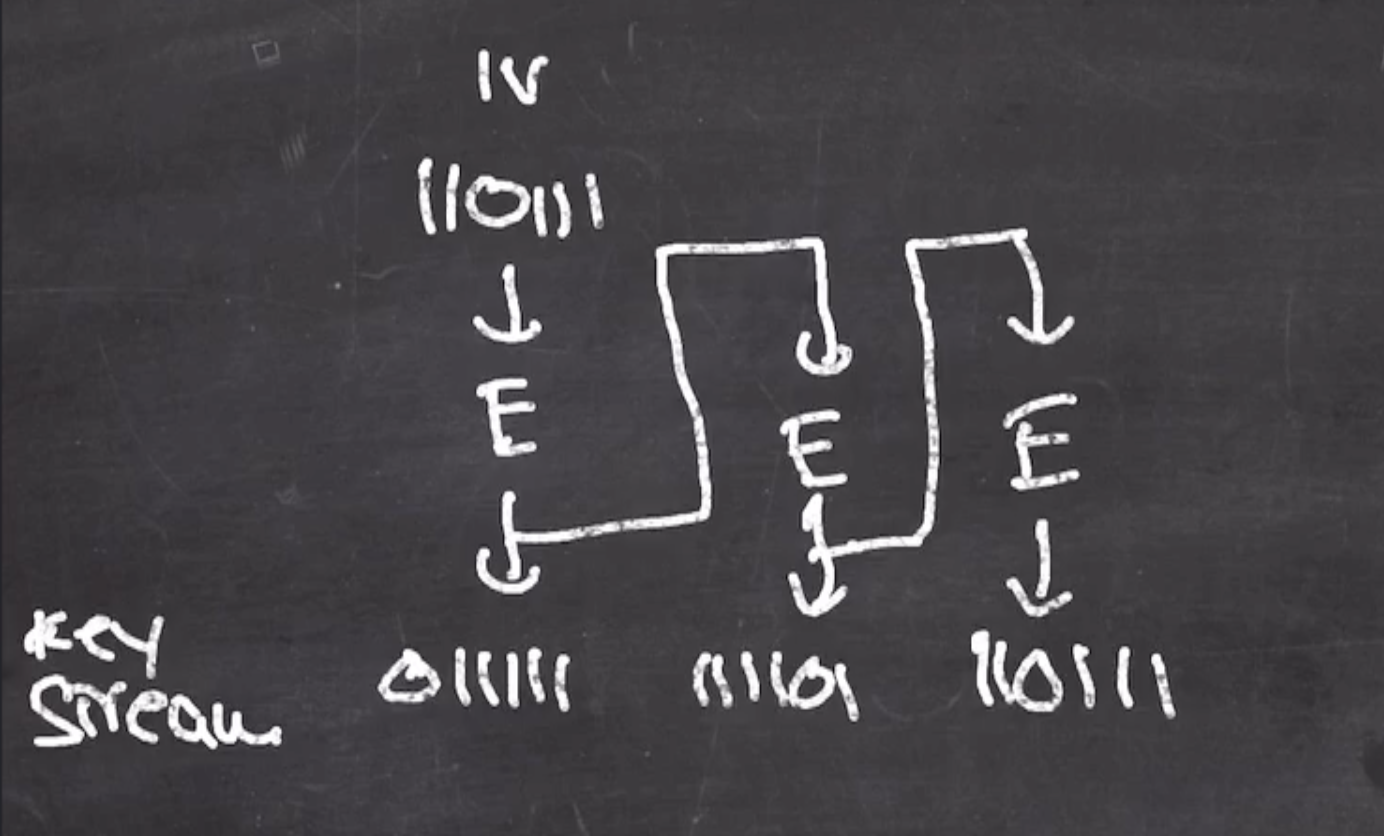

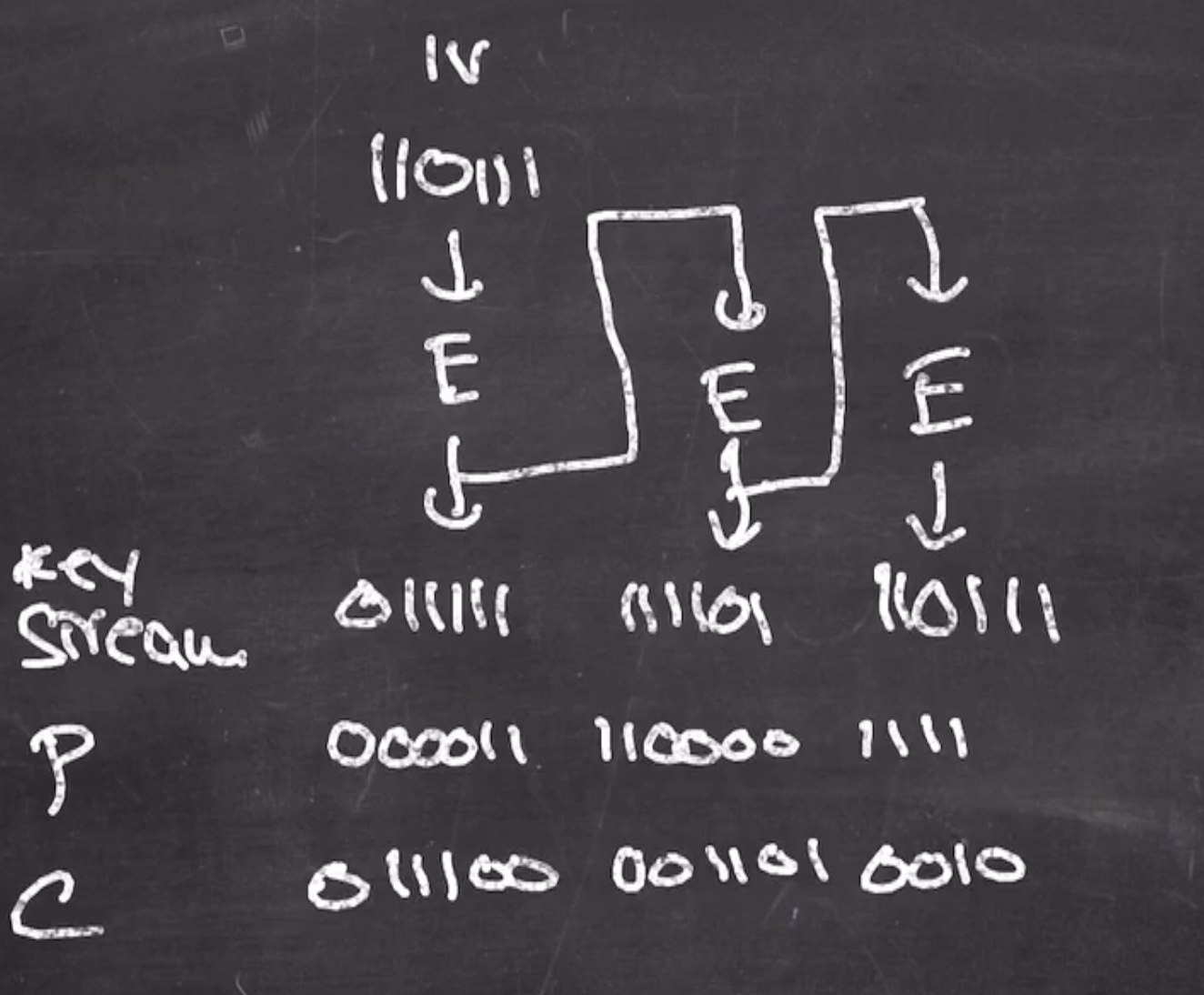

OFB #

Output feedback mode is also a stream cipher.

Recall

- Our initialization vector \( \text{IV} = 110111 \)

This goes through permutation \( E \) and generates the first block of the key stream.

The output block is then fed back into the next block

This process continues until you have enough bits of key stream to xor with your plaintext

Because its a stream cipher,

- To encrypt we can xor plaintext with the key stream to obtain the ciphertext. \[\begin{aligned} \text{ciphertext} = \text{plaintext } \oplus \text{ key stream} \end{aligned}\]

- To decrypt we can xor the ciphertext with the key stream to obtain the plaintext. \[\begin{aligned} \text{plaintext} = \text{ciphertext } \oplus \text{ key stream} \end{aligned}\]

AES #

AES is the standard block cipher used for symmetric encryption.

Recall, a block cipher is intended to resemble a random permutation. If we have a distinguisher with 2 worlds,

- a random world

- a block cipher with a random key

it should be hard to distinguish between the two worlds (this is how cryptographer’s can prove the strength of a block cipher).

File: Ch 4 slides

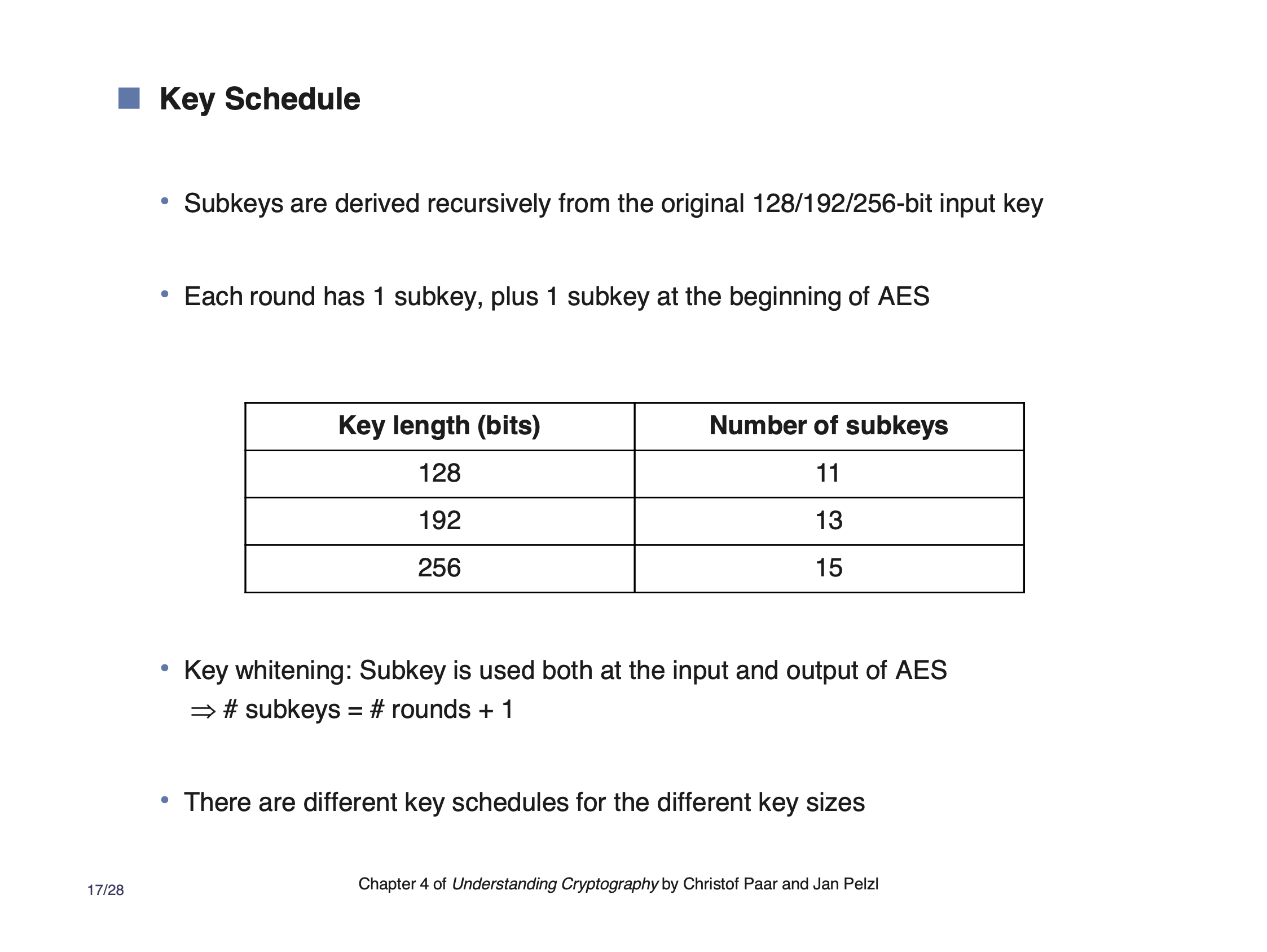

Since one iteration doesn’t give enough security, there are at least 10 rounds (depending on key size) to acquire as much confusion and diffusion as possible. Each round could be thought of as a weak block cipher, as if 10 weak block ciphers are composed. As we compose more and more ciphers, they become more and more random looking.

Structure #

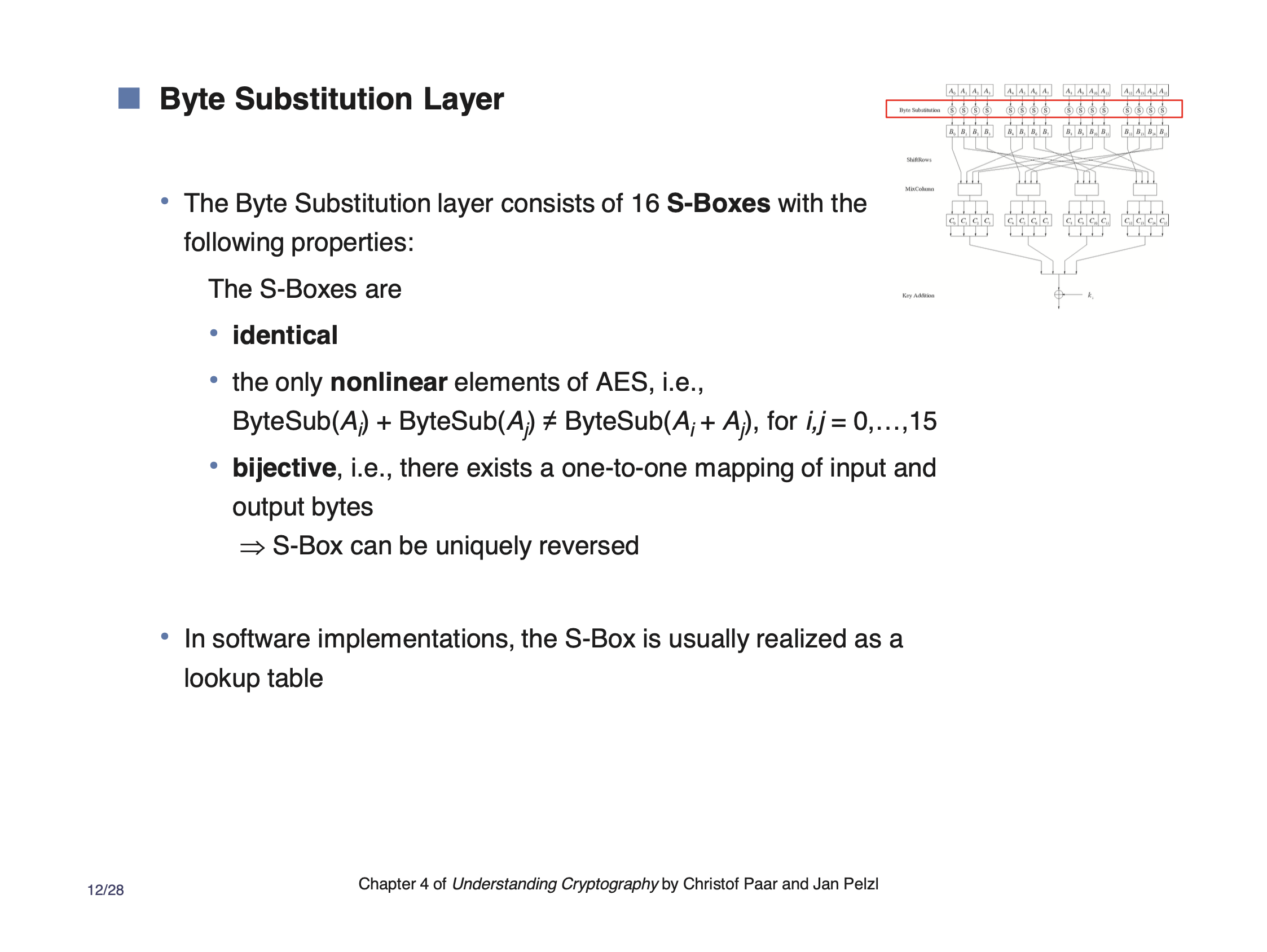

ByteSubstitution #

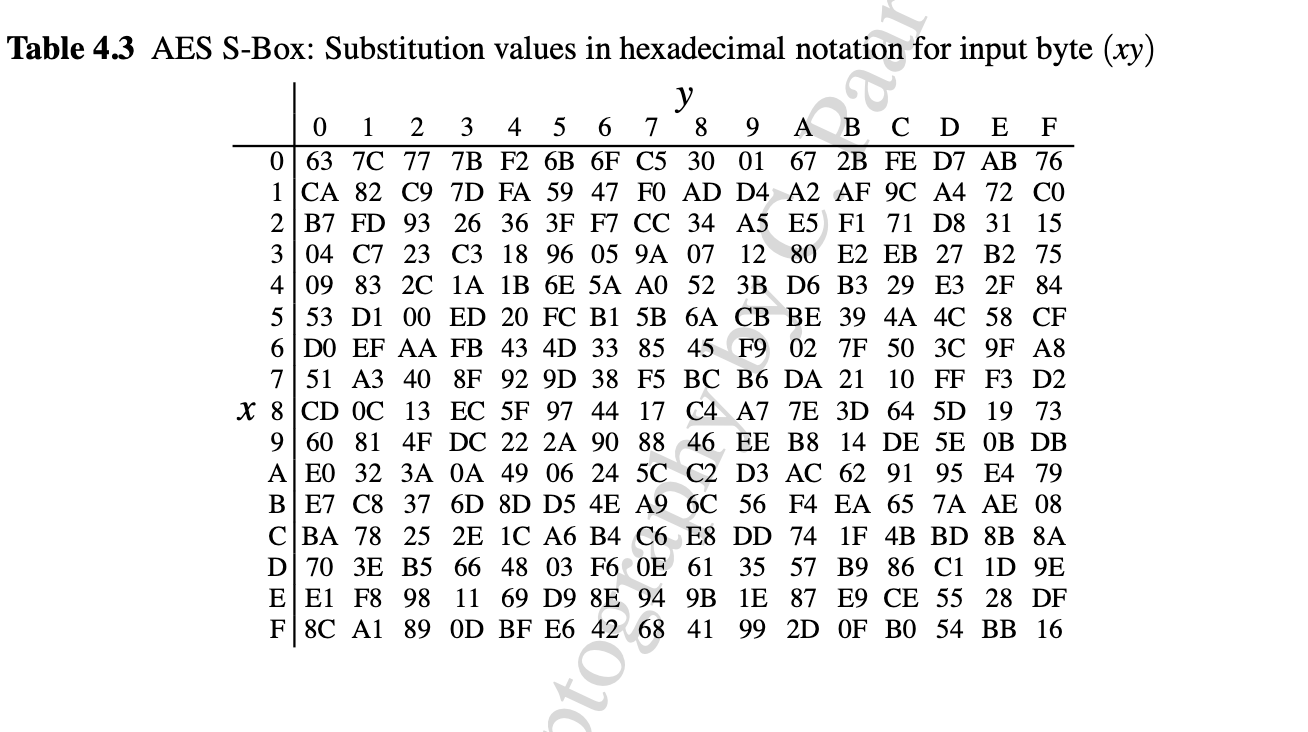

ByteSubstitution can be thought of as a 1 byte random permutation. Also called a S-Box (substitution box). This is the non-linear step, which is important because of the strength acquired from alternating between different mathematical structures. This adds confusion.

The ByteSubstitution is a Galois Field \( GF(2^8) \) ,

\[\begin{aligned} \text{ByteSubstitution } (x) = x^{-1} \cdot C_1 + C_2 \end{aligned}\]This is implemented as a look-up table.

ShiftRows #

ShiftRows rearranges the order of the data elements. Each group of 4 bytes is scattered across the range of the next layer. They each maintain their respective position, but they are scattered. This adds diffusion.

MixColumns #

MixColumns is another source of diffusion. It uses a cipher to scramble the 4 input bytes and which adds a smaller amount of local diffusion.

This is basically a system of equations.

If you had an input \( B = \text{0x03} \)

\[\begin{aligned} \text{0x02} \cdot B &= 00000010 \cdot 00000011 \\ &= x (x + 1) \\ &= x^2 + x \\ &= 00000110 \end{aligned}\]This leads to compact notation.

If we have 4 bytes coming into our MixColumns

We can find our output like by using the matrix multiplication,

We can use a \( GF(256) \) calculation to obtain the value

\[\begin{aligned} w &= 2A + 3B + C + D \\ &= (x)(x^2 + 1) + (x + 1)(x^4) + (x^4 + 1) + (x^2 + x) \\ &= (x^3 + x) + (x^5 + x^4) + (x^4 + 1) + (x^2 + x) \\ &= x^5 + 2x^4 + x^3 + x^2 + 2x + x^0 \\ &\text{mod coefficient by 2} \\ &= x^5 + x^3 + x^2 + x^0 \\ &= \text{0b}00101101 \\ &= \text{0x2D} \end{aligned}\]Key addition layer #

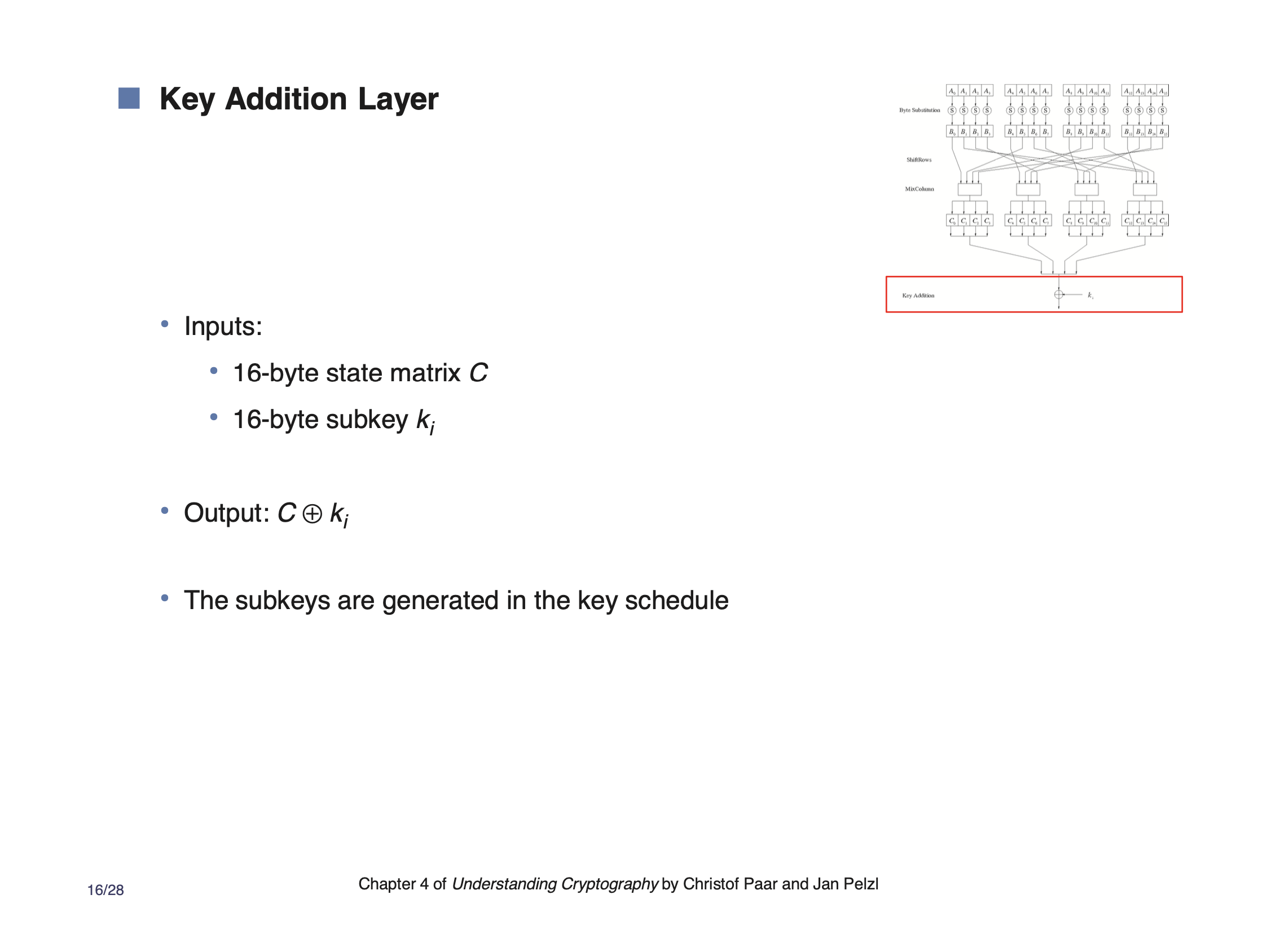

Note that the first key is xor’d directly with the plaintext. After that, the round key is generated using the last key using a simple transformation.

\( g \) is defined in this slide,

Usually, the 11 round keys are generated and kept in memory so its available each time the block cipher is used.

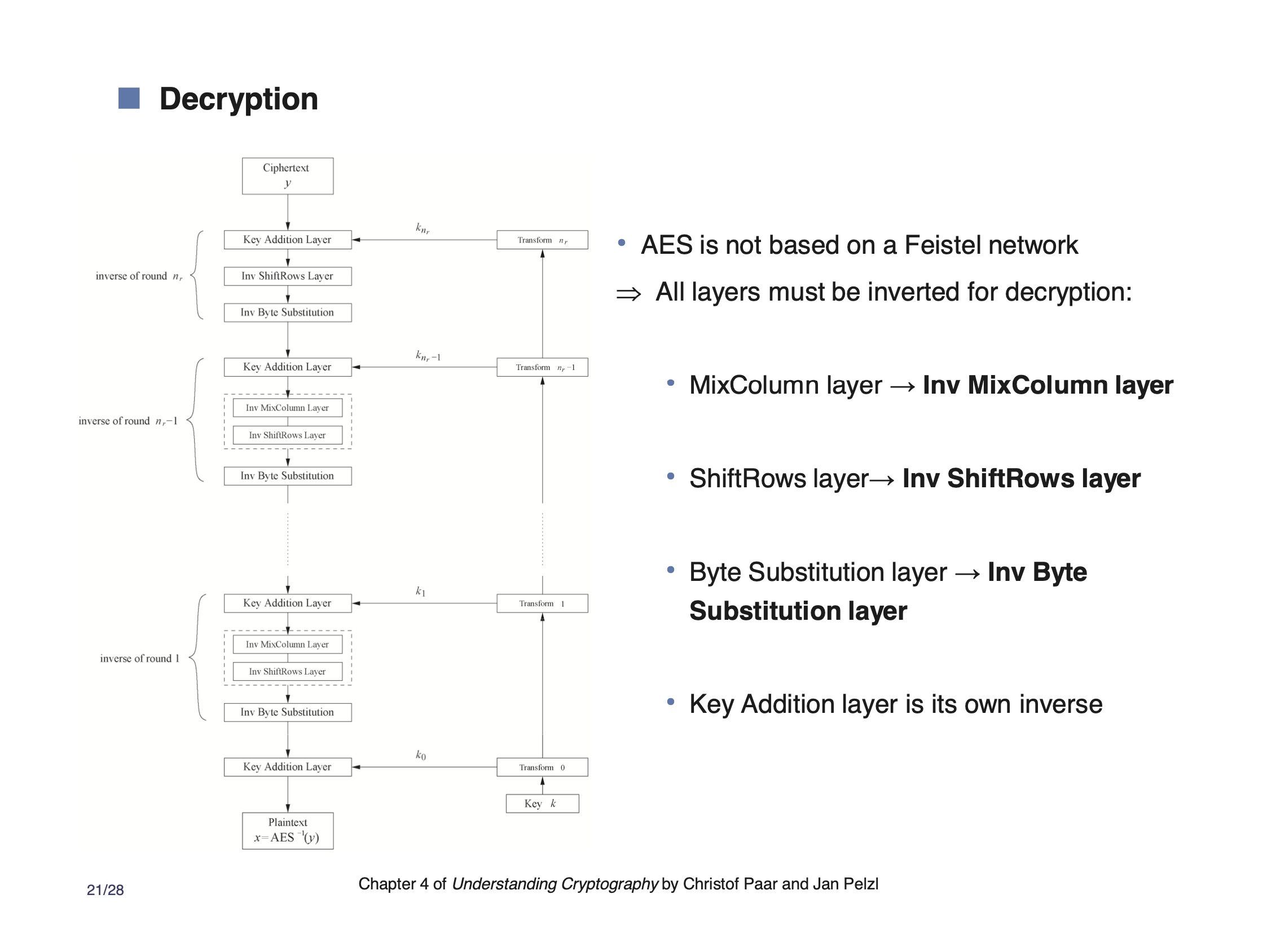

Decryption #

Introduction to SSE programming #

File: Intro to SSE pdf

We will stick to the original 16 byte wide registers for these examples.

mem 000102030405060708090a0b0c0d0e0f

reg 0f0e0d0c0b0a09080706050403020100 // intel does little-endian

SSE instructions can be told how to split up the register. For example if we split by 4

reg 0f0e0d0c 0b0a0908 07060504 03020100

There are a bunch of instructions that you can use on these elements.

Tips when programming with SSE #

See intrinsics in above pdf

When programming with SSE, we will be using compiler intrinsics. These intrinsic functions compile into 1 single assembly instruction.

Link: Intrinsics documentation, use SSE2

Since we don’t have an intrinsic rotate instruction in SSE2, we need to do the split rotate and or the result to achieve the rotation.

Some SSE example code #

Consider,

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <immintrin.h>

#include <time.h>

// accumulator function

uint32_t sum(uint32_t * buf, int n)

{

uint32_t res = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++)

{

res = res + buf[i];

}

return res;

}

int main(int argc, char * argv[])

{

// allocate 4 million bytes

uint32_t * buf = malloc(1000000 * 4);

// read timer

clock_t t = clock();

// sum all elements

uint32_t total = sum(buf, 1000000);

// get elapsed time

t = clock() - t;

printf("%u\n", (unsigned) t);

}

When this runs it outputs

4790

which is different on each run, because it is measuring the amount of ticks it takes to complete the calculation. (They are averaging around 3000).

Lets see if we can do better using SSE instructions. Instead of reading each element individually, lets read them in groups of 4.

We can modify our sum function to use SSE instructions, we’ll call it sum_sse:

uint32_t sum_sse(uint32_t * buf, int n)

{

uint32_t res_arr[4];

__m128i res = _mm_setzero_si128(); // 0 0 0 0

for (int i = 0; i + 4 < n; i = i + 4)

{

// load current element

__m128i temp = _mm_loadu_si128((__m128i *)(buf + i));

// add to sum

res = _mm_add_epi32(res, temp);

}

// store res into memory

_mm_storeu_si128((__m128i *) res_arr, res);

// return sum of 4 elements

return res_arr[0] + res_arr[1] + res_arr[2] + res_arr[3];

}

When we run this we get an average output time of around 1500, so while this was harder to write, it is a lot faster.

Note: To sum the 4 values in our

resvalue, we could do something like this:1 2 3 4 0 1 2 3 shift right 1 3 5 7 sum last 2 0 0 1 3 shift right twice 1 3 6 10 sum last 2 10 our answerHowever, we just write

resback to memory and then sum the result of that.

Introduction to SSL programming #

While SSL was introduced for securing network connections, we aren’t going to use it in that way. We will be using the open source toolkit because it contains implementations of almost everything we’re learning in the class.

To tell what version of openssl we’re on:

openssl version

- Docs: OpenSSL documentation

- Wiki: OpenSSL wiki

- Source: OpenSSL crypto source code

We will be using the EVP authenticated encryption and decryption.

We will be using the evp.h header file.

So lets write something using some openssl code to make sure our environment is working, in a file called test.c:

#include <openssl/evp.h>

int main()

{

// make a call to some kind of openssl function

EVP_aes_128_ctr();

return 0;

}

We can compile with, linking the crypto lib

gcc -lcrypto test.c

An OpenSSL encryption example #

Lets encrypt something, note

- OpenSSL uses contexts, whatever the encryption mode needs is in the context.

We allocate them in the stack, ie

EVP_CIPHER_CTX *ctx;- init this with

EVP_CIPHER_CTX_new()

- init this with

- We aren’t handling errors robustly here, for brevity

- In order to stay in our cryptographic model, our key should be random bytes. However for brevity we are using a simple key.

- To specify what block cipher and mode of operation, we call

EVP_EncryptInit_exand pass it- a pointer to our context

- specifier for what block cipher / mode

- an

ENGINE *, we will always putNULL. This value is if you have a special implementation of your mode of operation. - a pointer to the key, 16 bytes long

- a pointer to the initialization vector, we’ll use our nonce when we create

iv

EVP_EncryptUpdate’s name including the word “update” indicates that it does not encrypt all the data at once.EVP_EncryptFinalis called to finalize the encryption- if there is anything in the buffer, it would pad/encrypt/write, needs a pointer to where to continue writing bytes should there be any in the buffer

EVP_CIPHER_CTX_freeis used to clean up allocated memory- securely releases memory

#include <stdio.h>

#include <openssl/evp.h>

int main()

{

/* ENCRYPTION */

// plaintext

char pt[44] = "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog";

char pt2[44];

// ciphertext

char ct[44];

// key (should be random)

unsigned char key[16] = {1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,0,1,2,3,4,5,6};

// nonce || counter

unsigned char iv[16] = {1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1};

// our cipher context

EVP_CIPHER_CTX * ctx;

ctx = EVP_CPHER_CTX_new();

EVP_EncryptInit_ex(ctx, EVP_aes_128_ctr(), NULL, key, iv);

// do the encryption

int len; // how many bytes written

int ciphertext_len;

EVP_EncryptUpdate(ctx, ct, &len, pt, 44);

ciphertext_len = ciphertext_len + len;

// finalize, then free context

EVP_EncryptFinal(ctx, ct + ciphertext_len, &len);

ciphertext_len = ciphertext_len + len;

EVP_CIPHER_CTX_free(ctx);

/* DECRYPTION */

// reset counter block

iv[15] = 1;

// reinit context

EVP_DecryptInit_ex(ctx, EVP_aes_128_ctr(), NULL, key, iv);

// do the decryption

len = 0;

int plaintext_len;

EVP_DecryptUpdate(ctx, pt2, &len, ct, 44);

plaintext_len = plaintext_len + len;

// finalize, then free context

EVP_DecryptFinal_ex(ctx, pt2 + plaintext_len, &len);

plaintext_len = plaintext_len + len;

EVP_CIPHER_CTX_free(ctx);

// lets check if it worked

printf("%s\n", pt2);

}

gcc -lcrypto test.c

./a.out

The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog