Tail recursion and accumulators #

Tail recursion #

Claim: recursive overhead is expensive.

Not always the case.

For example:

We have a function foo(x) that takes a parameter x.

foo(x):

if (x == 0)

return answer

else

// do stuff, then make recursive call

return foo(x - 1)

The value of x is being decremented, and being passed in as the new x in the next call.

Once the base case is returned there isn’t any more work that needs to be done.

So we can rewrite this function mechanically as a loop:

foo(x):

label

if (x == 0)

return answer

else

// do stuff, but instead of return

// we update our variable, and goto label

x = x - 1

goto label

This behaves exactly as the original, in terms of computational steps, but we’ve eliminated the function call so the overhead goes away. This only works if the recursive call is in tail position, which is a recursive call at the very end of the work that has no work to do after the recursive call. So you get the performance of a loop, but with the written style of recursive code.

So lets do the factorial:

fact(x):

if (x == 0)

return 1

else

return x * fact(x - 1)

So we should assume that the compiler should be able to tail call optimize this code. However, there is a multiplication that has to occur after the function call, so it cannot.

So we can fix this by getting rid of the multiplication by x.

If there is multiplication that needs to happen, it has to happen before the recursive call.

We can do this using accumulators.

An example accumulator:

acc = 1

while (x > 0)

acc = acc * x

x = x - 1

return acc

So we can use that same idea to modify our fact function:

fact(x, acc):

if (x == 0)

return acc

else

return fact(x - 1, x * acc)

Now the last function call is in tail position. There is no computation that happens after the recursive call.

Invariant: \(\text{answer} = x! \cdot \text{ accumulator } \)

x |

acc |

|---|---|

| 4 | 1 |

| 3 | 4 |

| 2 | 12 |

| 1 | 24 |

| 0 | 24 |

Proof that this works using C #

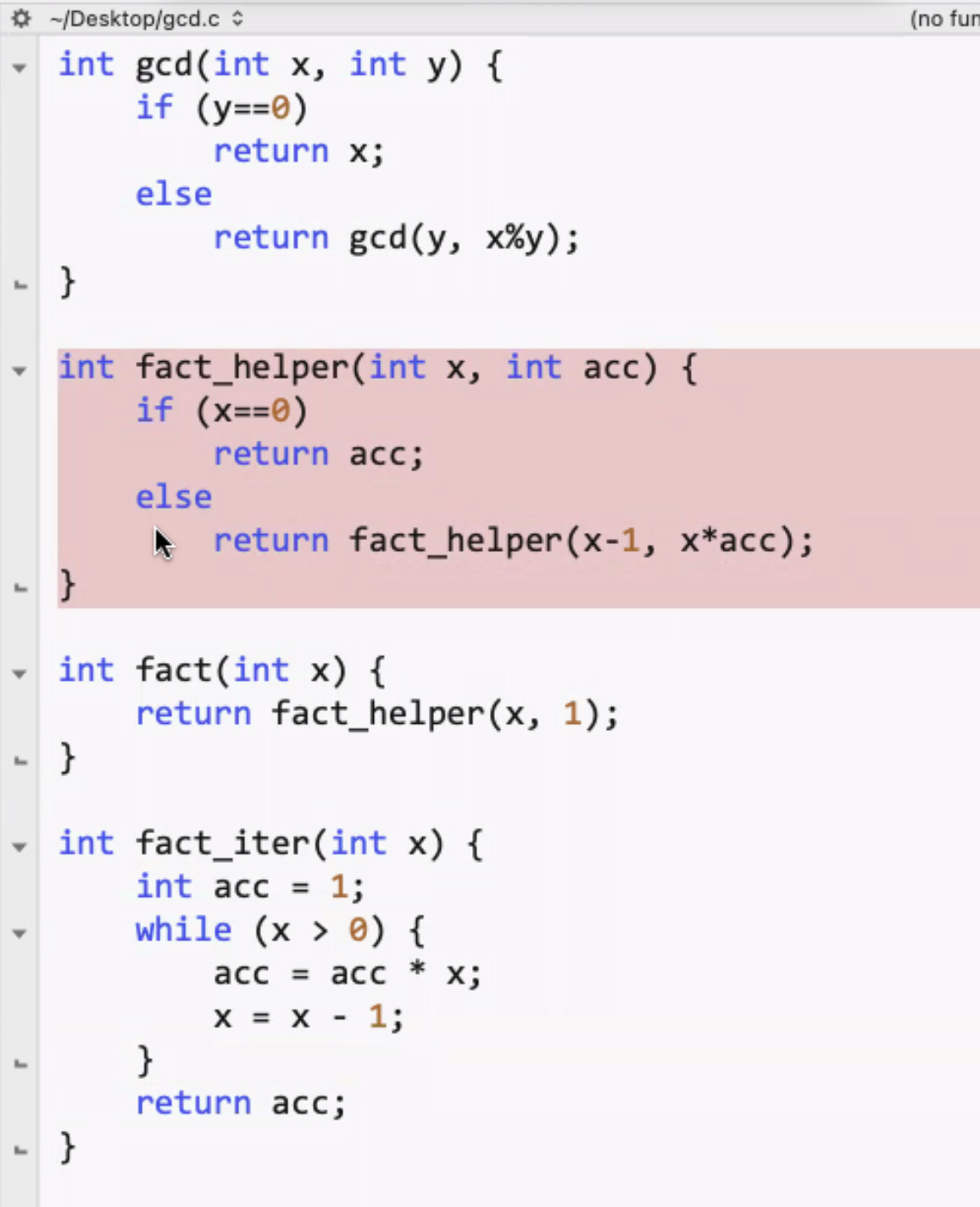

Using C code and looking at its compiled assembly:

gcd.c:

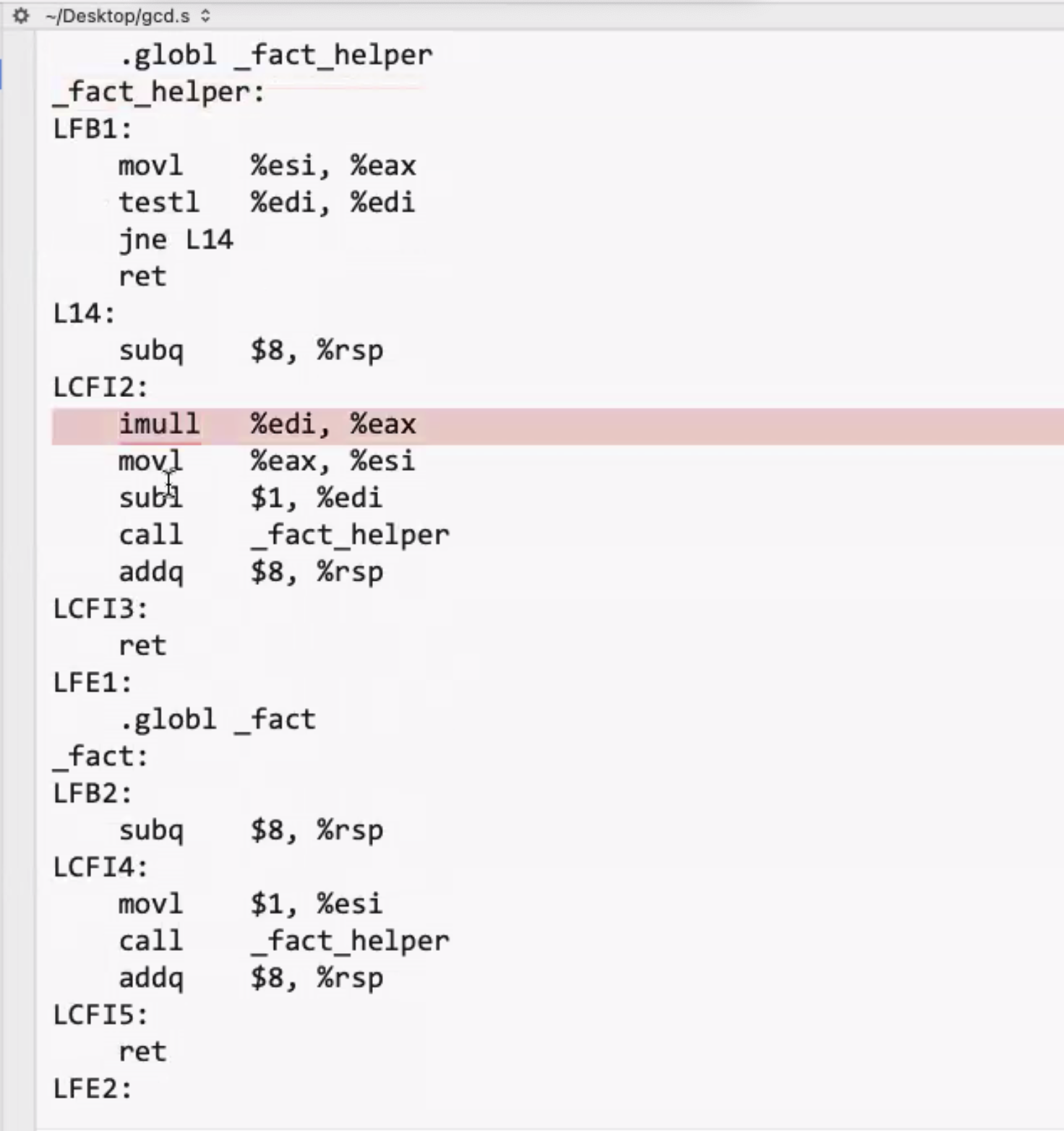

We can compile this with optimization level 1:

gcc -01 gcd.c -S

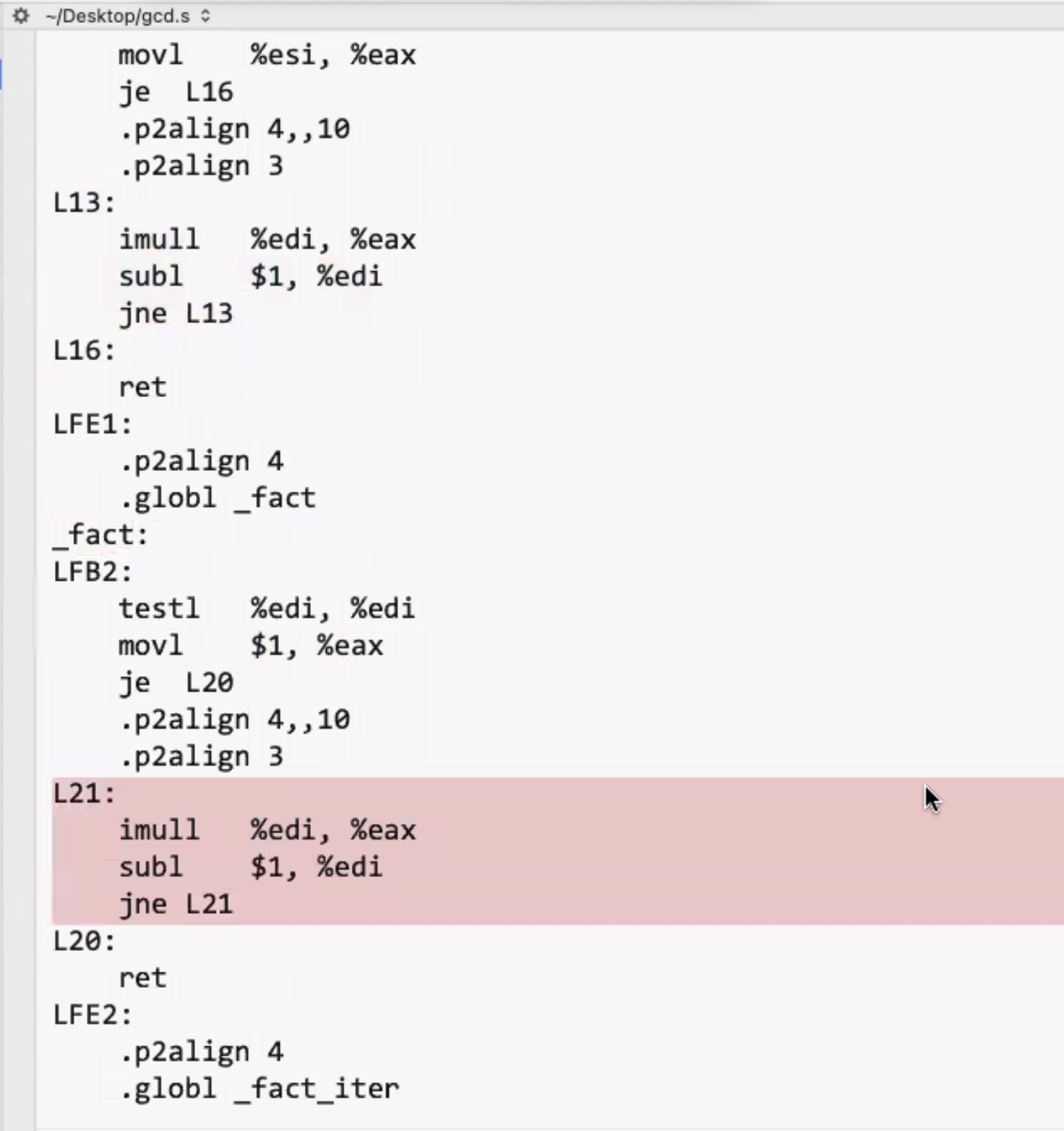

Lets do optimization level 2 (adds tail call optimization):

gcc -01 gcd.c -S2

This is now a tighter loop instead of a recursive call. It also inline calls the helper function to fact:

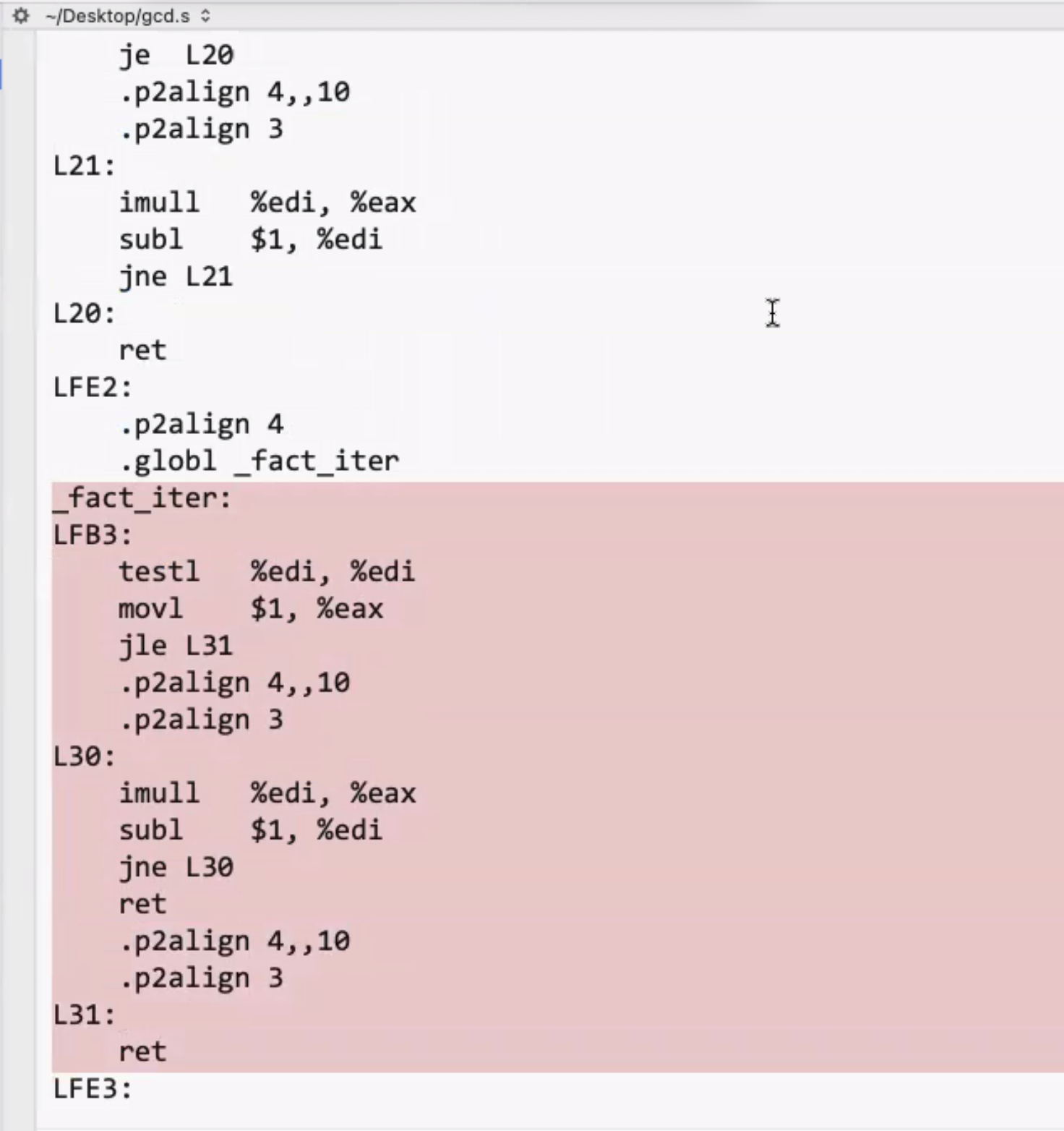

The iterative version is identical to the inline factorial version:

The gcd function is also a tail recursive function.

It could be written iterative however:

int gcd_iter(int x, int y)

{

while (y != 0)

{

int t = y;

y = x % y;

x = t;

}

return x;

}

This is arguably a more complex version, compared to the recursive version. Lets look at the compiled assembly code:

It has a loop, but no recursive calls. The iterative version:

It also has the same length loop, so they are identical, due to the tail call optimization.

Factorial method implementation in Racket #

Here is a tail recursive version.

(define (fact-helper x acc)

(if (= x 0)

acc

(fact-helper (- x 1) (* x acc))))

To test this:

(fact-helper 4 1) ; 24

We can also define a nicer method for the user:

(define (fact x) (fact-helper x 1))

So now we can call it like this:

(fact 4) ; 24