Recurrences cont #

Recursion tree method #

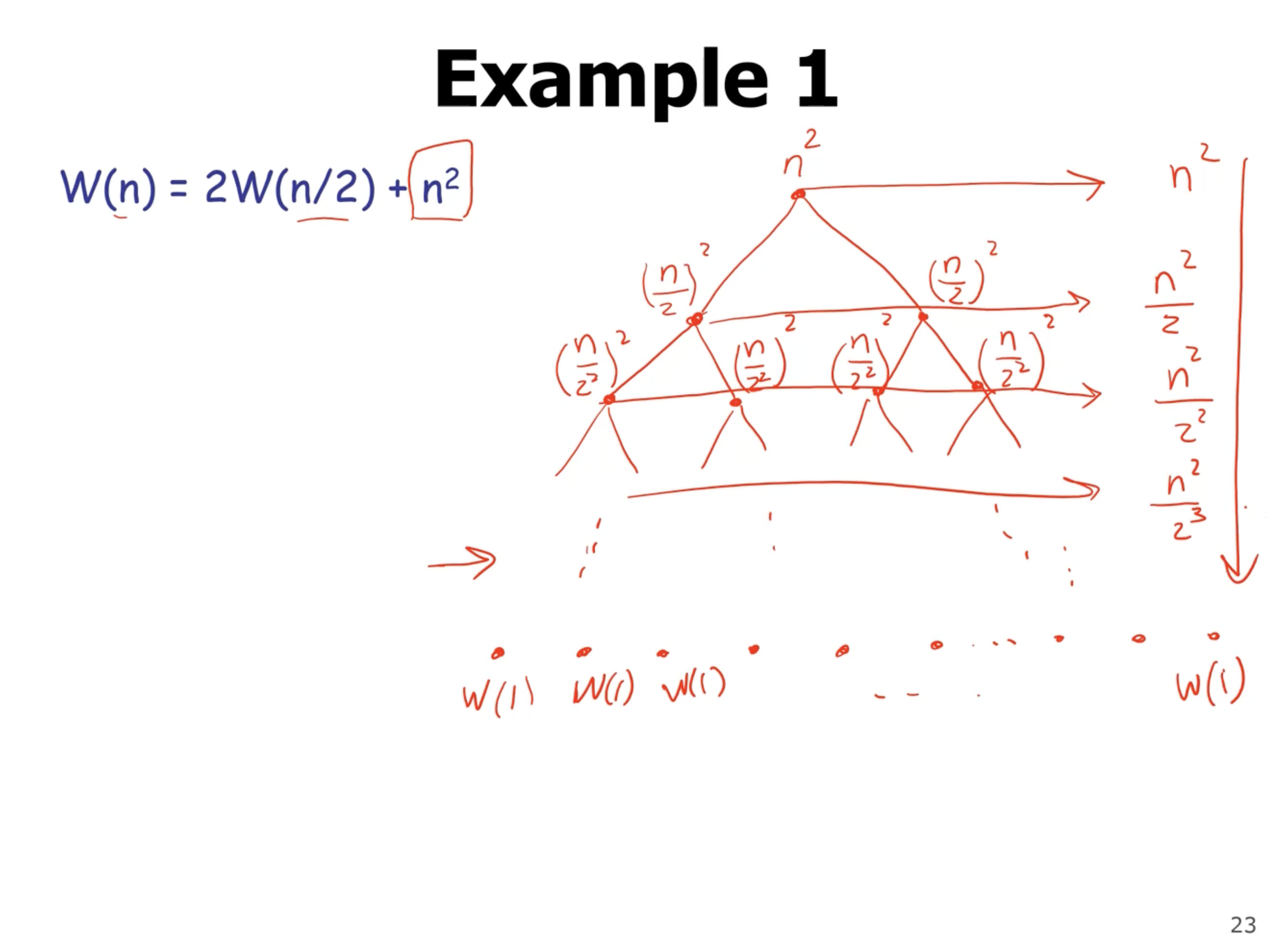

Another method to solve recurrences is to draw a recursion tree, where each node gets a cost. The cost of each node is the additional work done on each recursive call (not recursive call itself).

The leaf nodes are the base cases. The idea is to identify a pattern, and use a known series to evaluate that pattern.

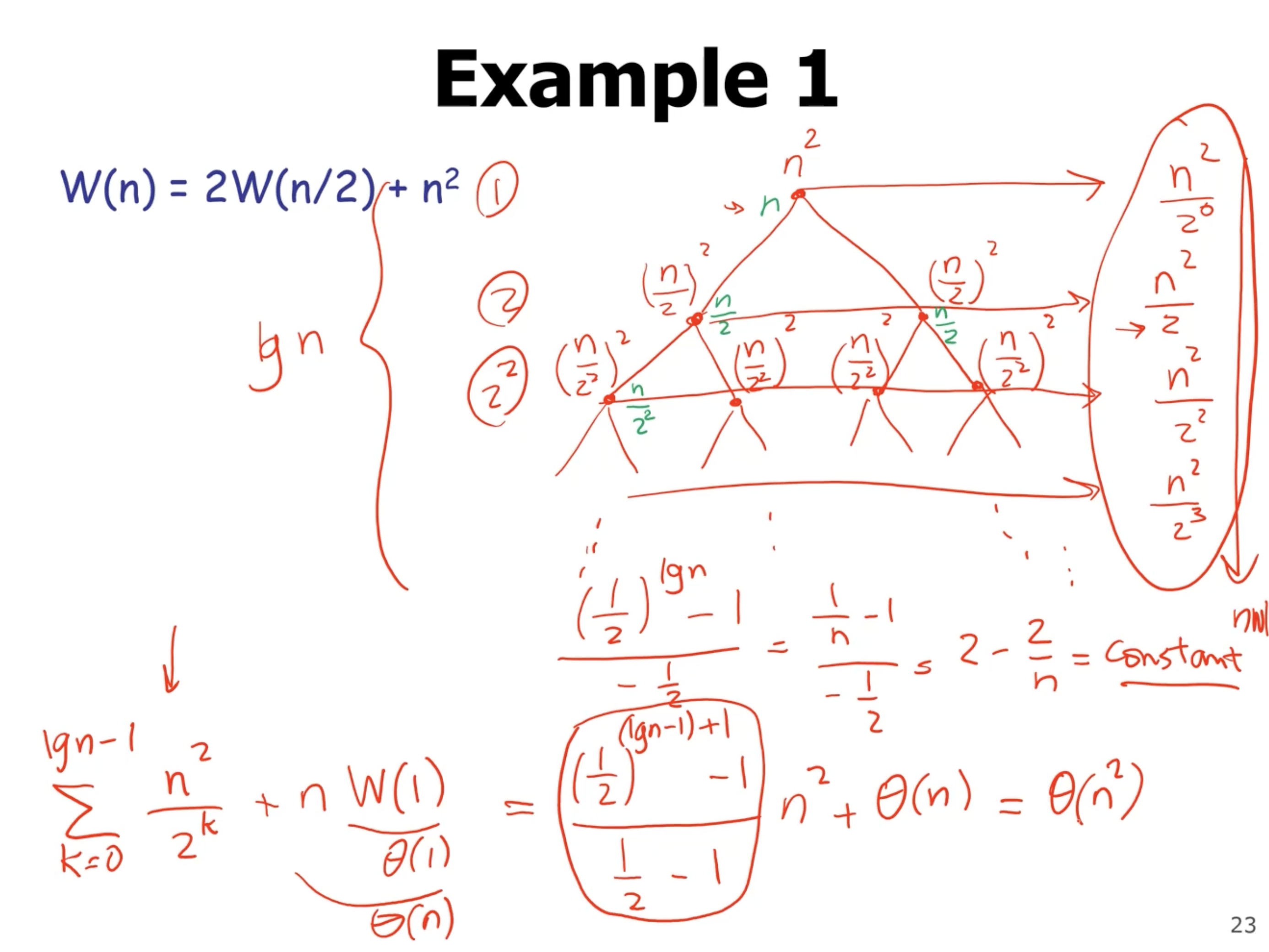

Then, after identifying the sum of each level of the tree, you then sum all the level’s themselves (except the base level, the leaves). Notice that the height of this tree is \( \lg n \) . We can sum all the levels up to the last one (notice that \( k \) goes to \( \lg n \) ). Then, add the cost of the last level (there are \( 2^{\lg n} = n \) leaf nodes). So we can describe this summation like this:

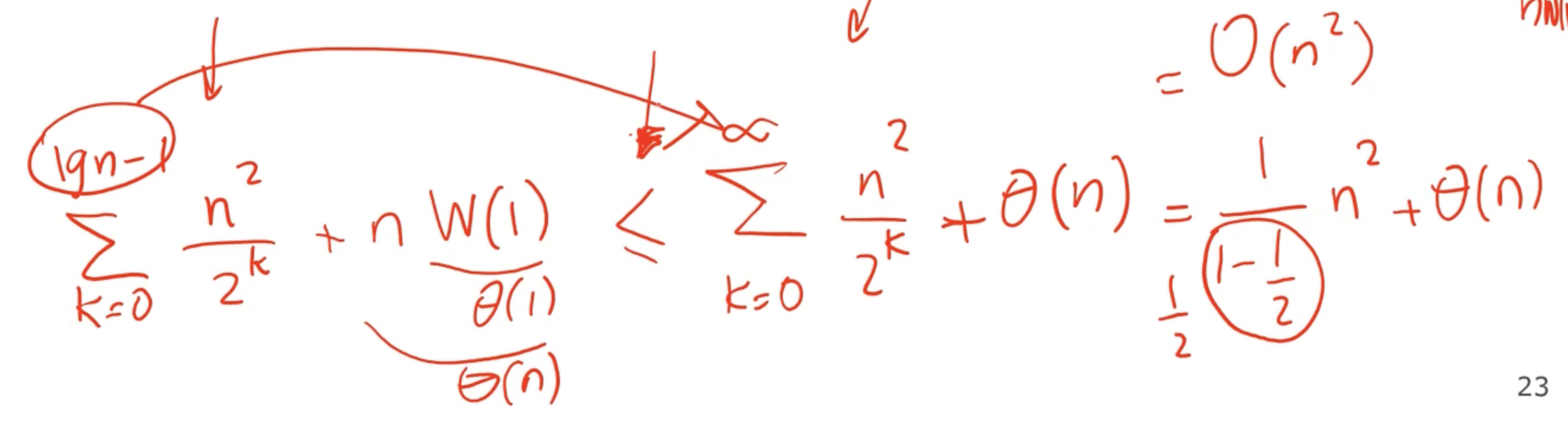

\[\begin{aligned} \sum_{k=1}^{\lg n} \frac{n^2}{2^k} + n W(1) &= \frac{\frac{1}{2}^{(\lg n - 1) + 1} -1}{\frac{1}{2} - 1} n^2 + \Theta(n) \\ &= \left( 2 - \frac{2}{n} \right) n^2 + \Theta(n) \\ &= \Theta(n^2) \end{aligned}\]

Its okay to also let \( n \to \infty \) and get an approximation:

However, don’t make the approximation too loose.

This gives an overall complexity of \( \Theta(n^2) \) .

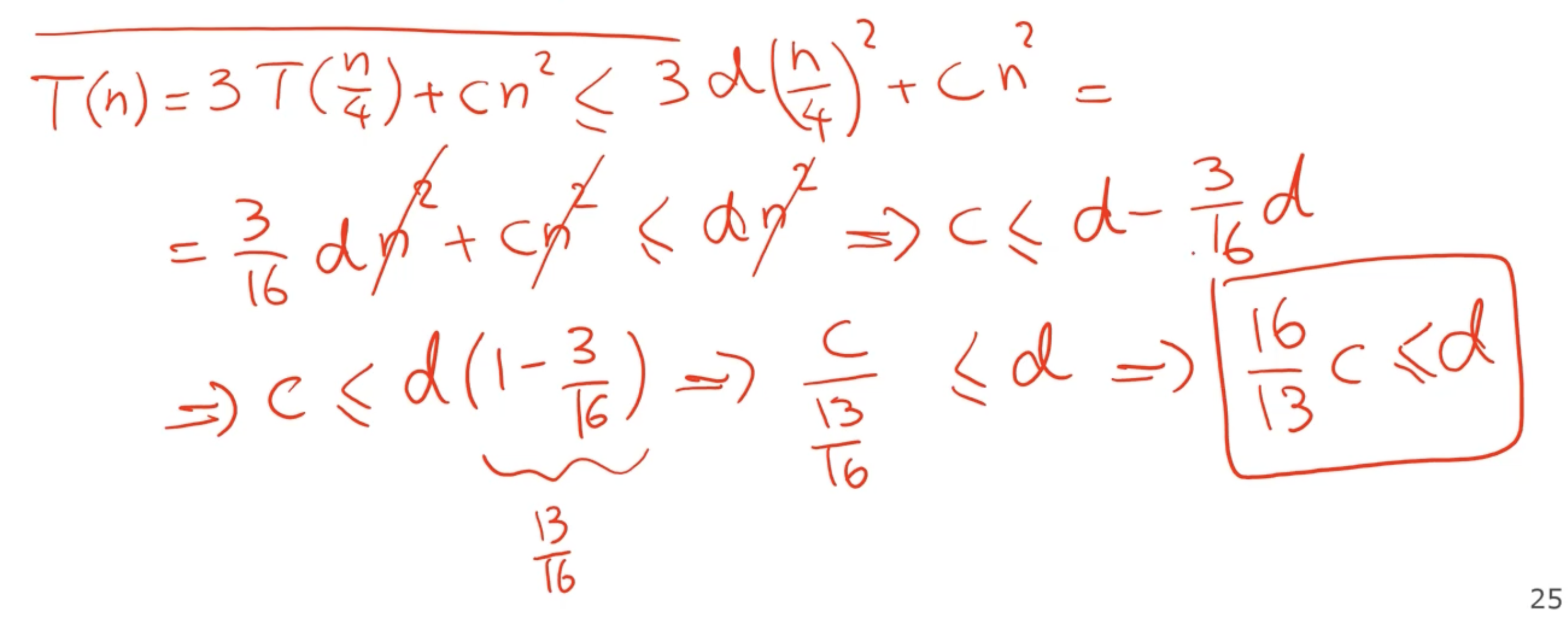

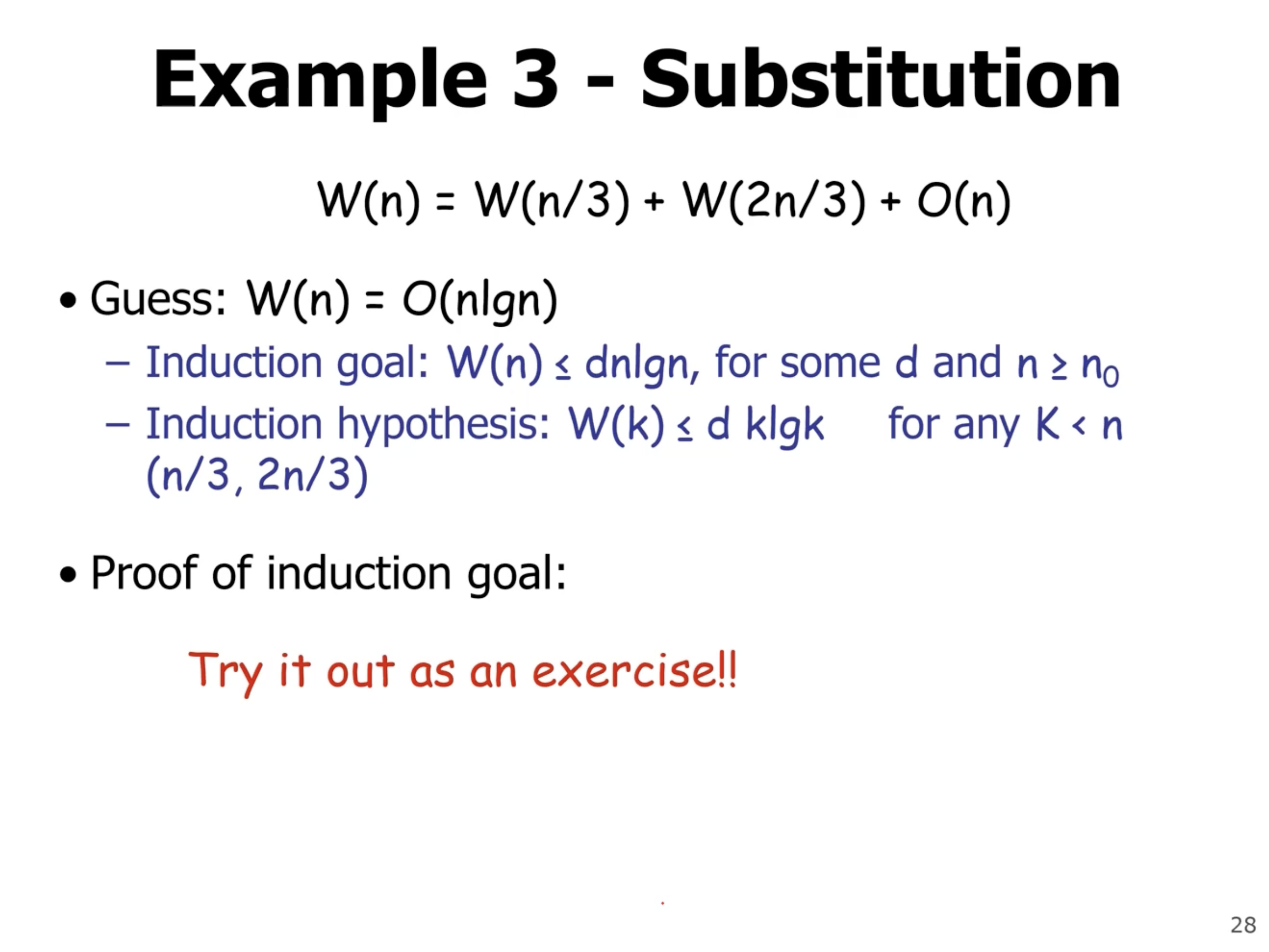

Lets solve this same problem using the substitution method.

Once this is setup, we can solve for \( d \) .

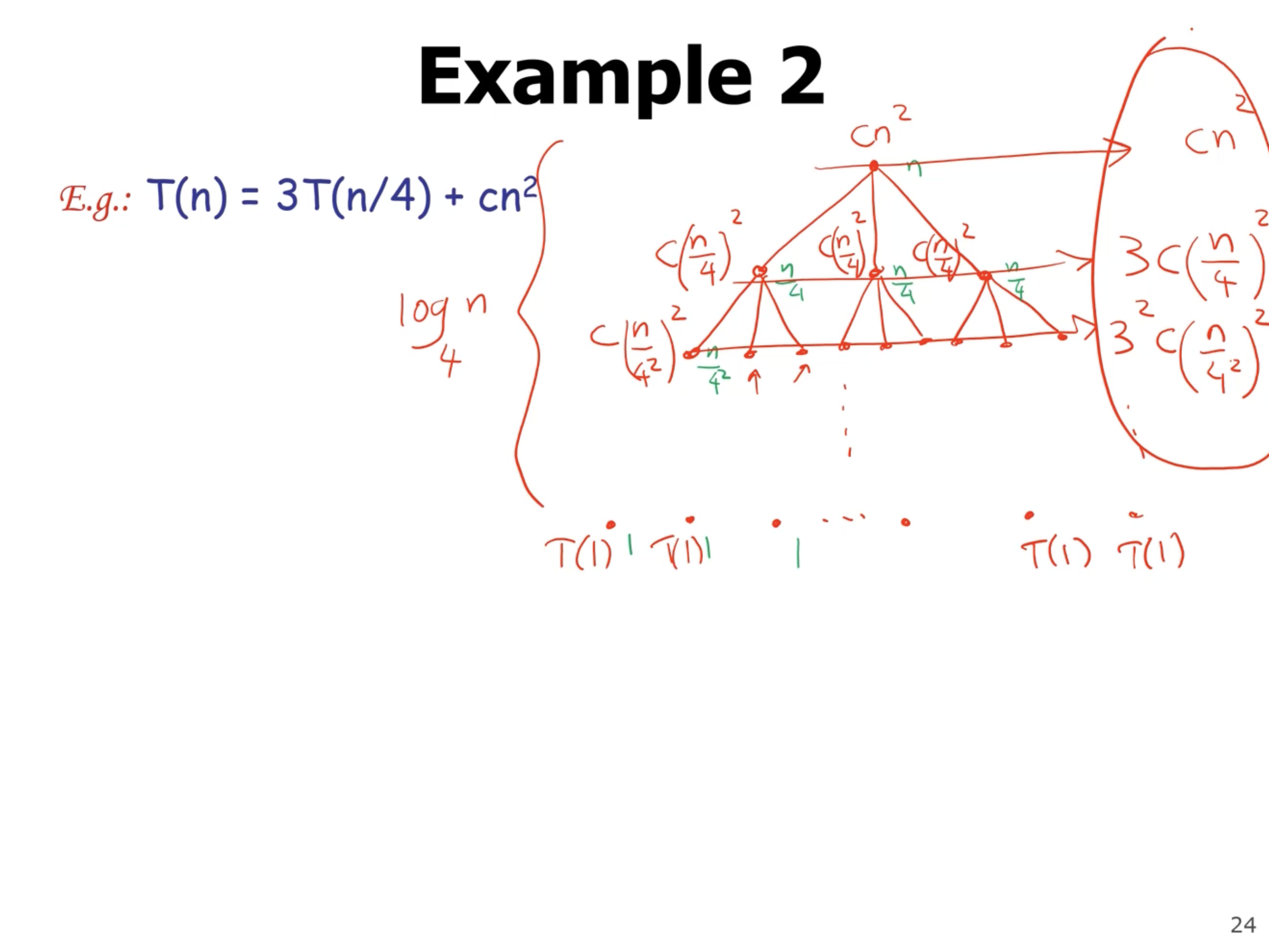

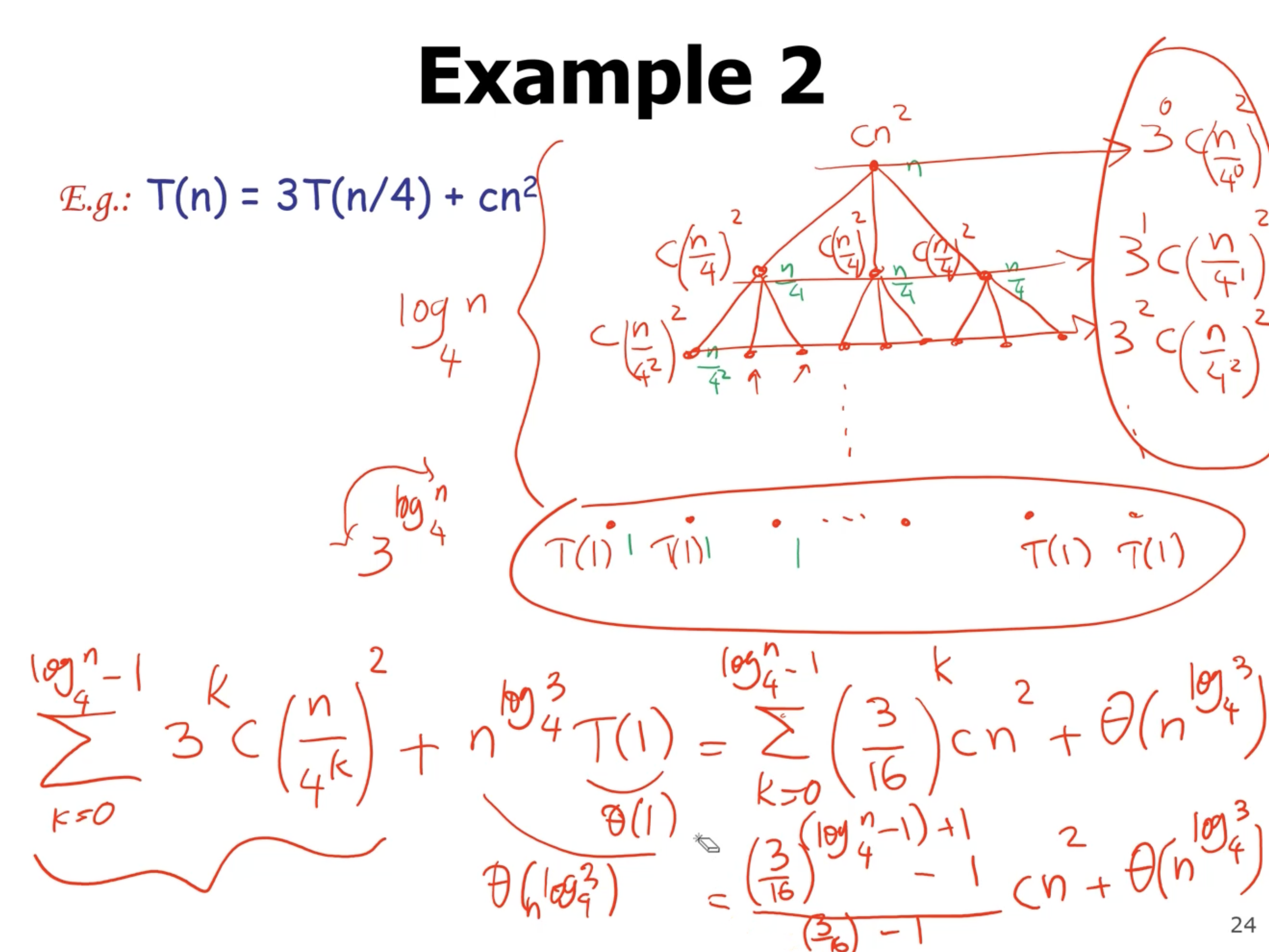

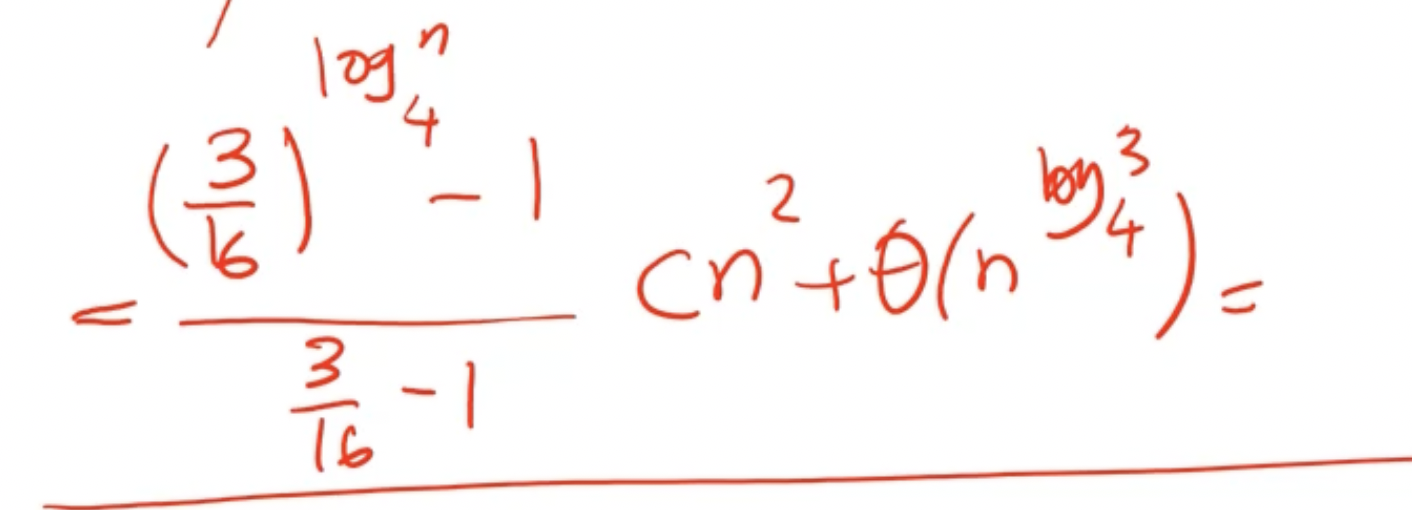

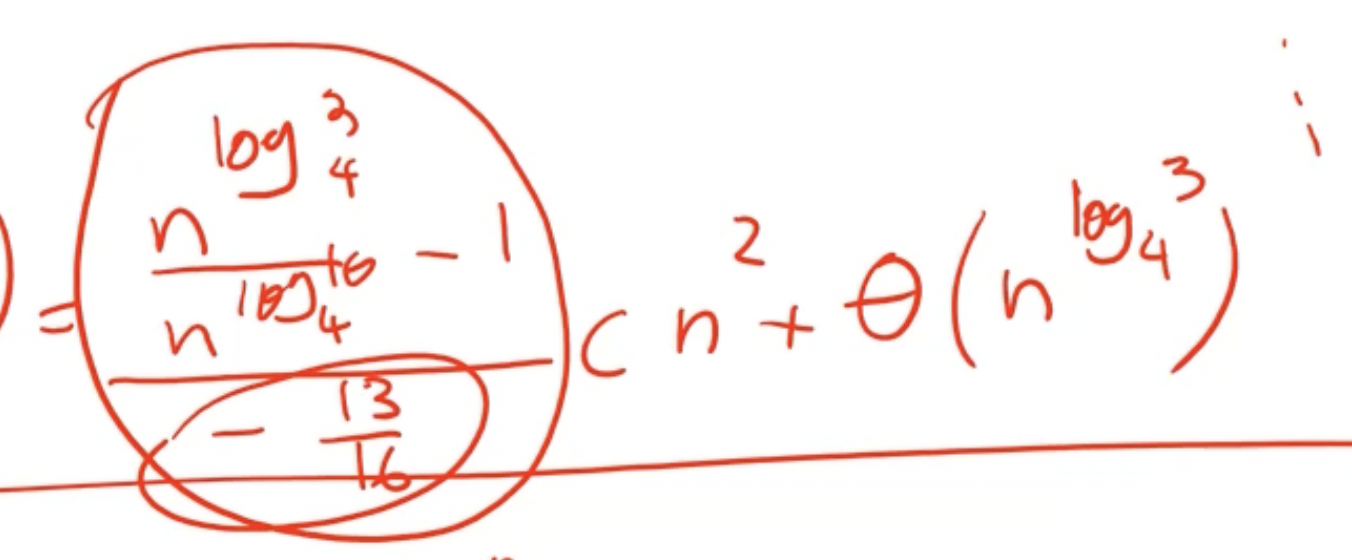

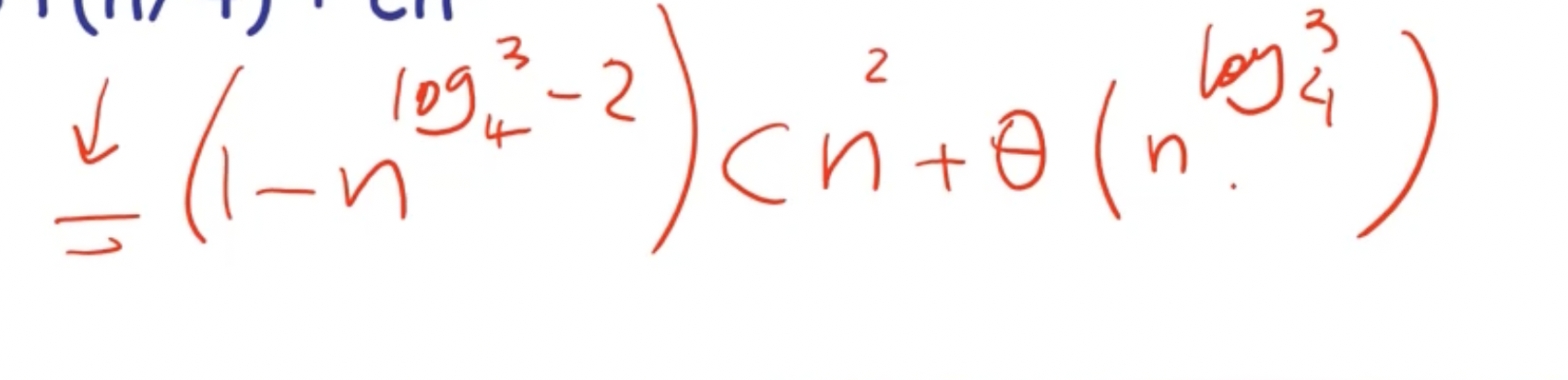

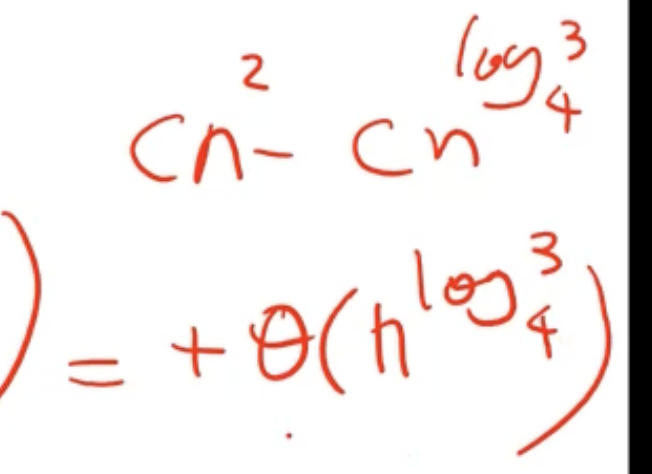

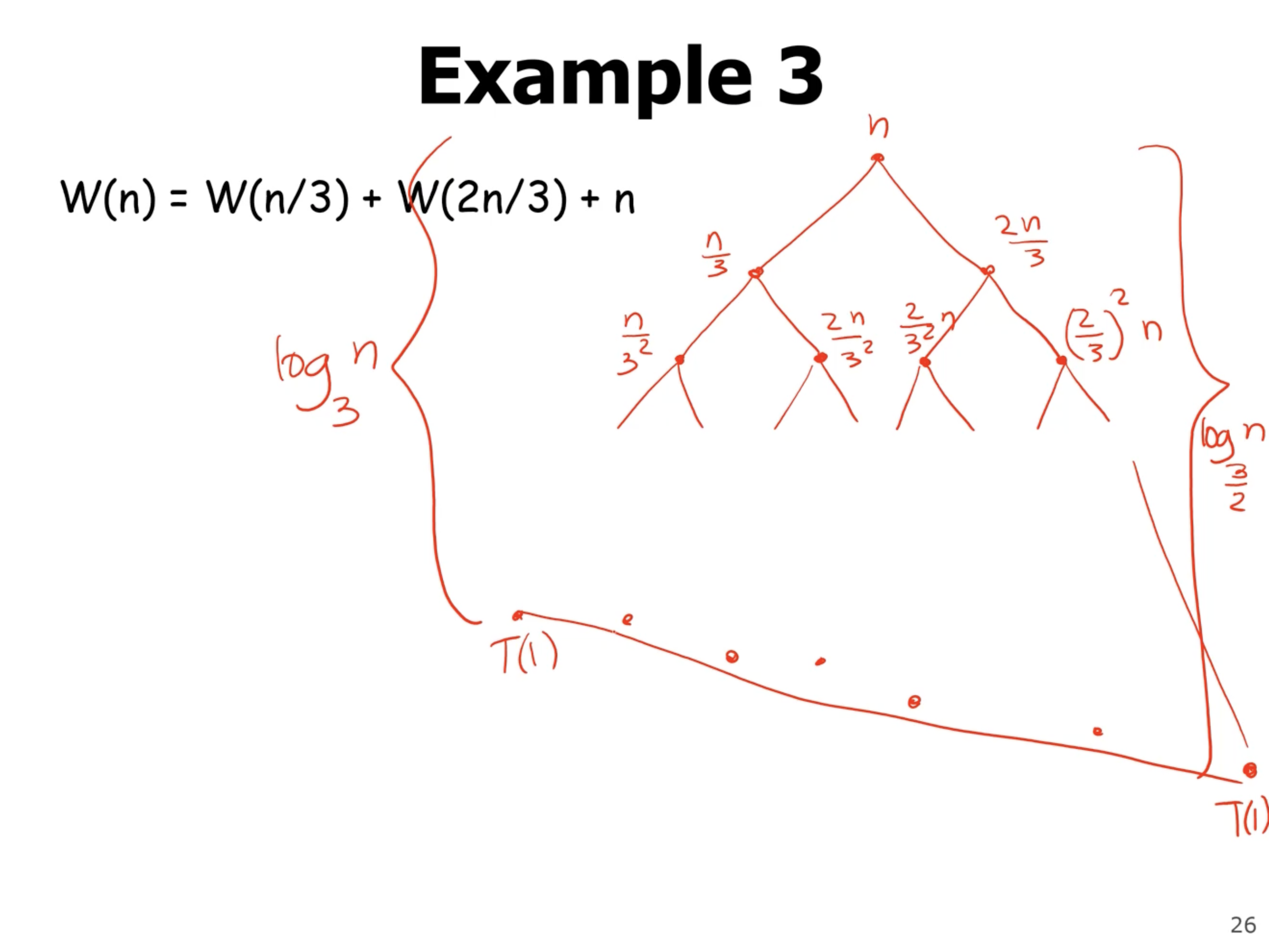

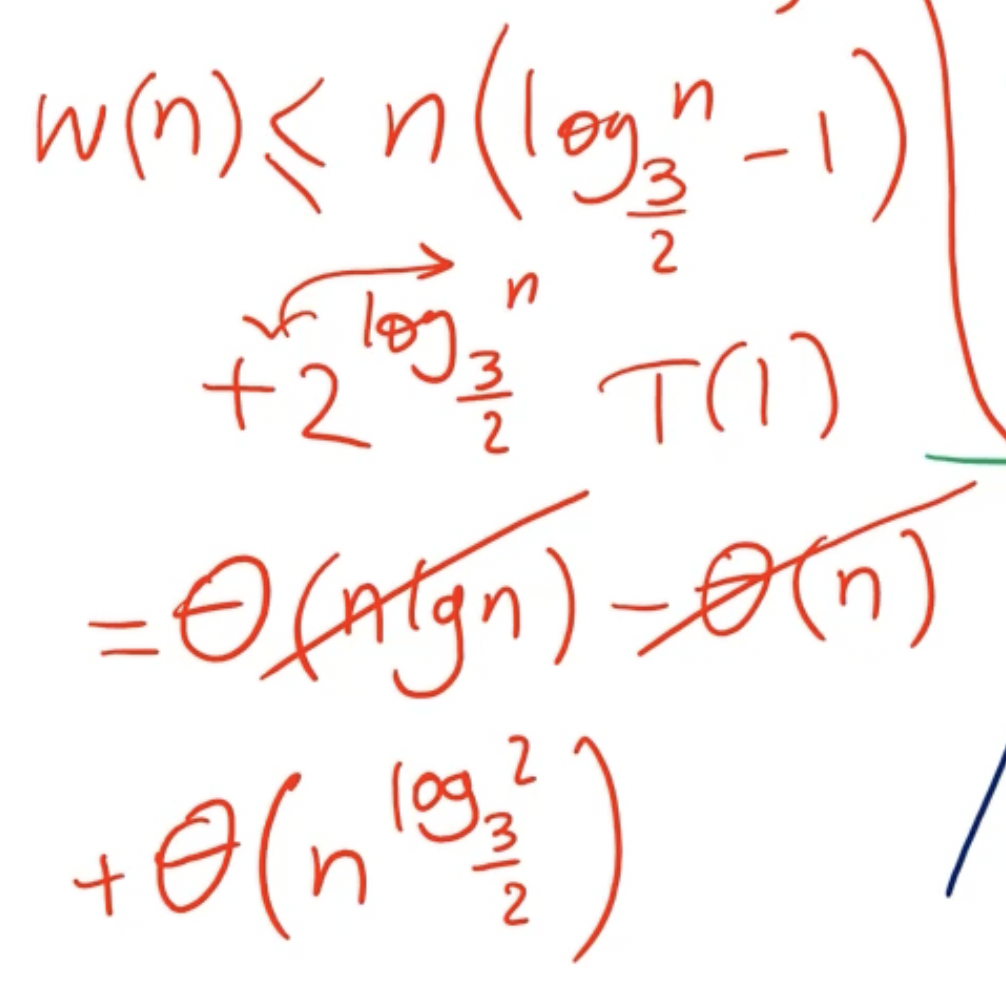

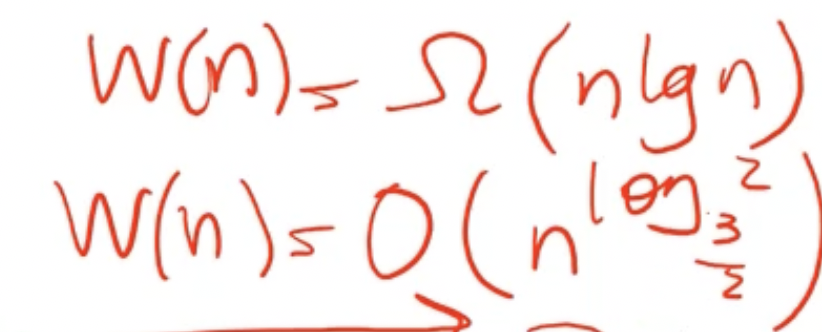

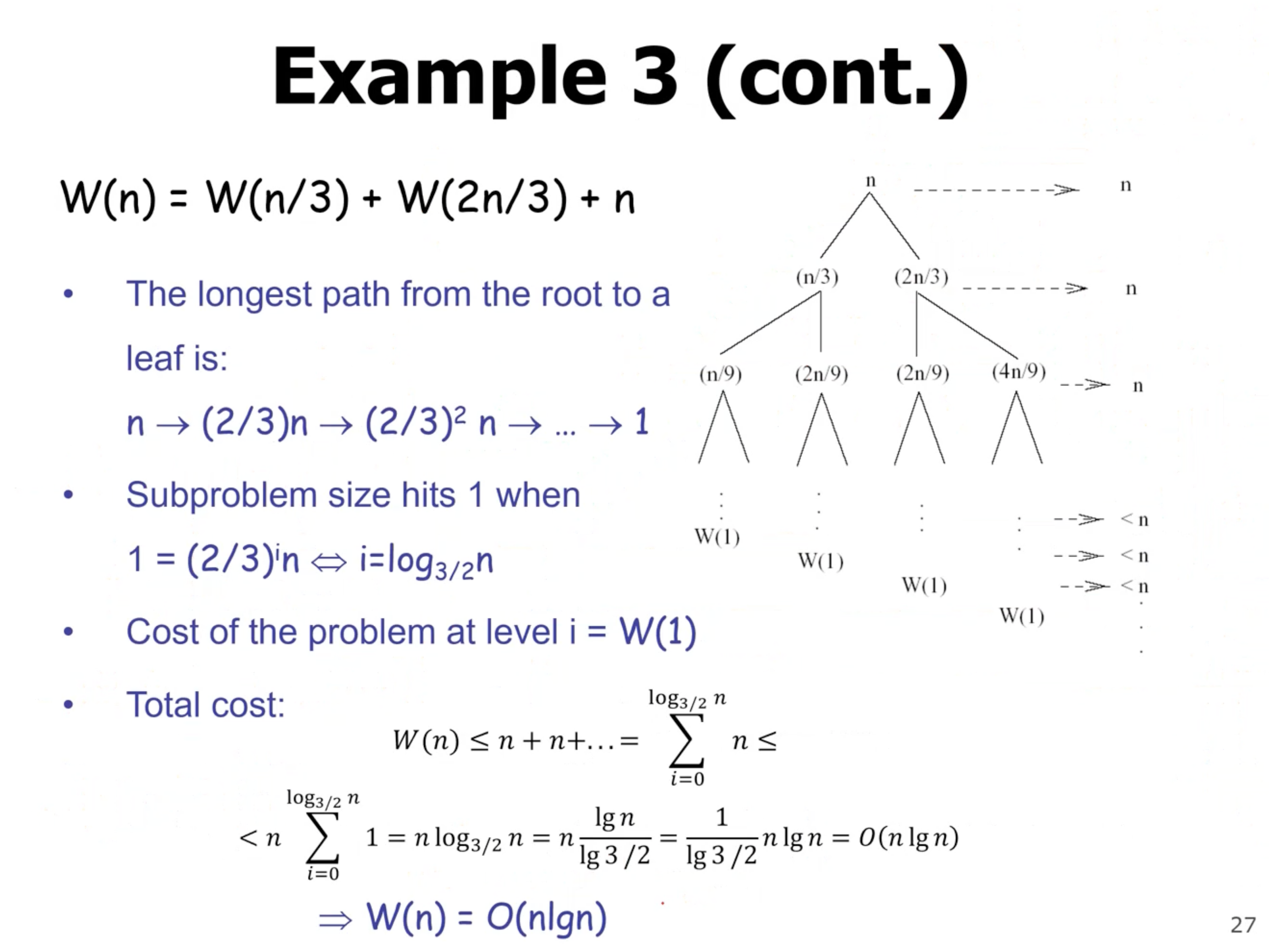

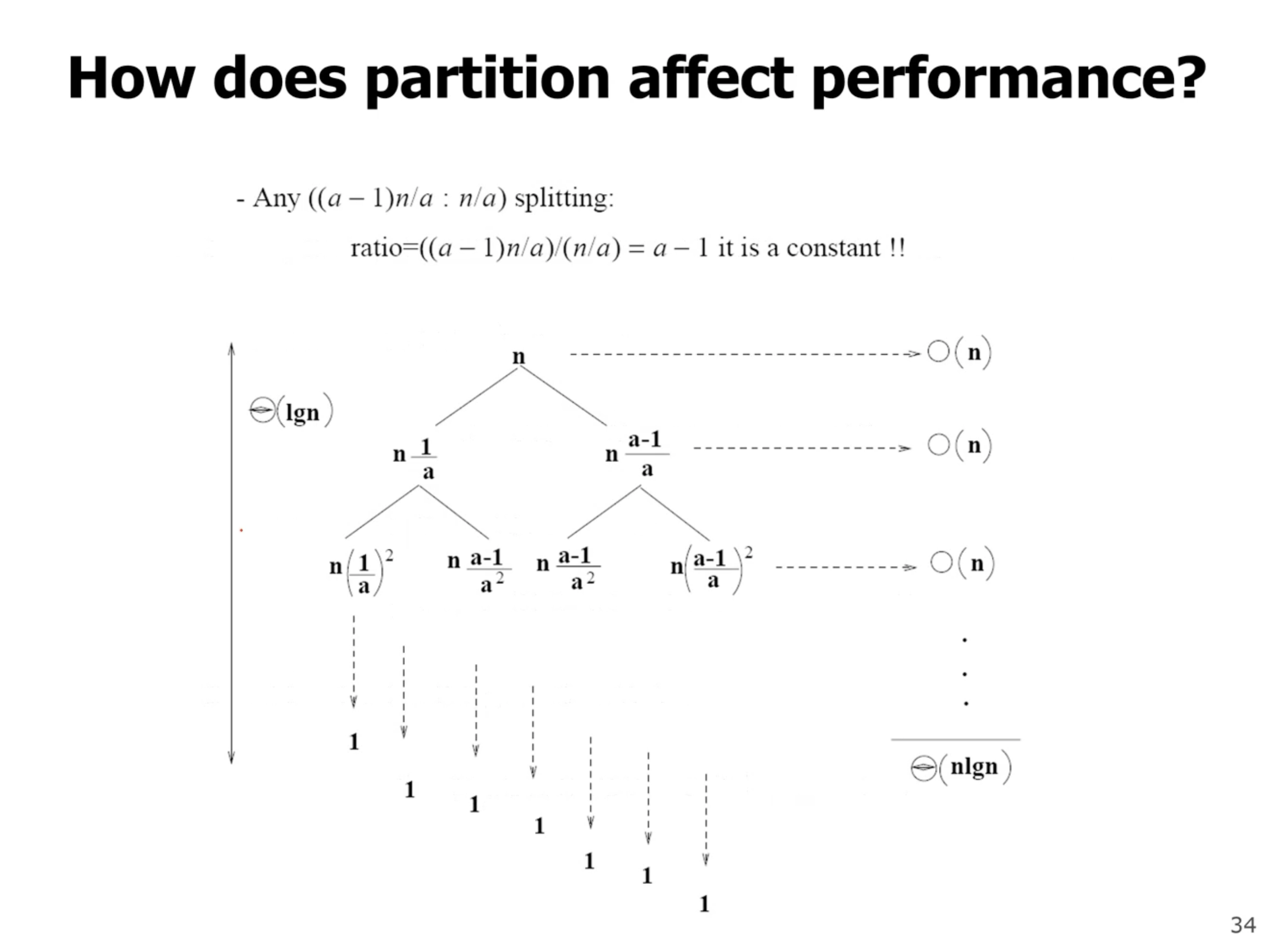

Now, lets try an unbalanced tree:

When we have an unbalanced tree, we need to find the height of the root to leaf nodes that reach the base case the fastest, and the height of the root to leaf nodes that reach the base case the slowest. When we start to sum each level, we can see each level costs \( n \) , until the tree becomes unbalanced. At this point, the cost is \( \leq n \) .

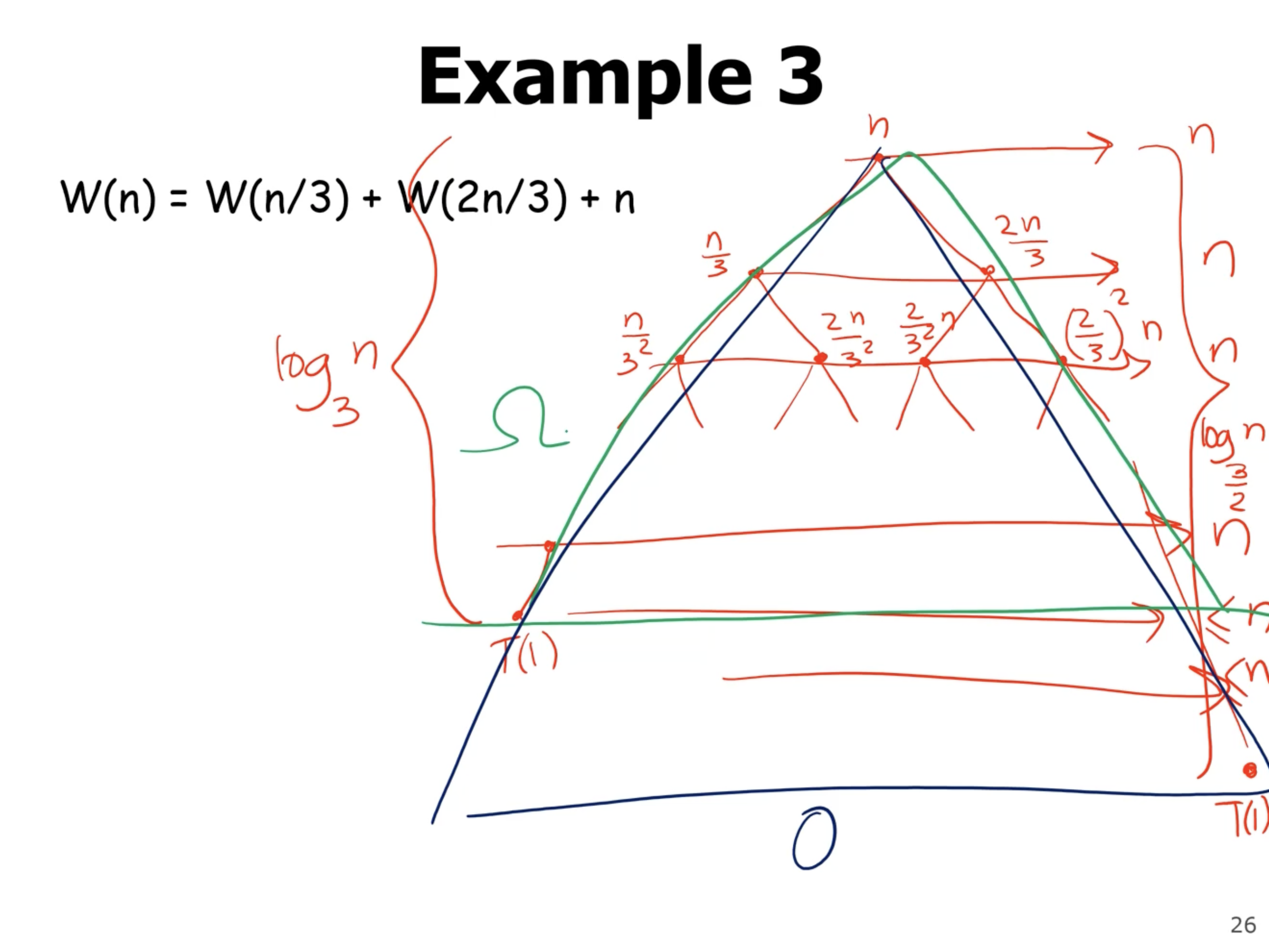

Note: If we assume the cost at each level is in fact \( n \) , then we will find an upper bound for the complexity. If we assume that the tree ends at the shortest path from root to leaf, then we will get the lower bound.

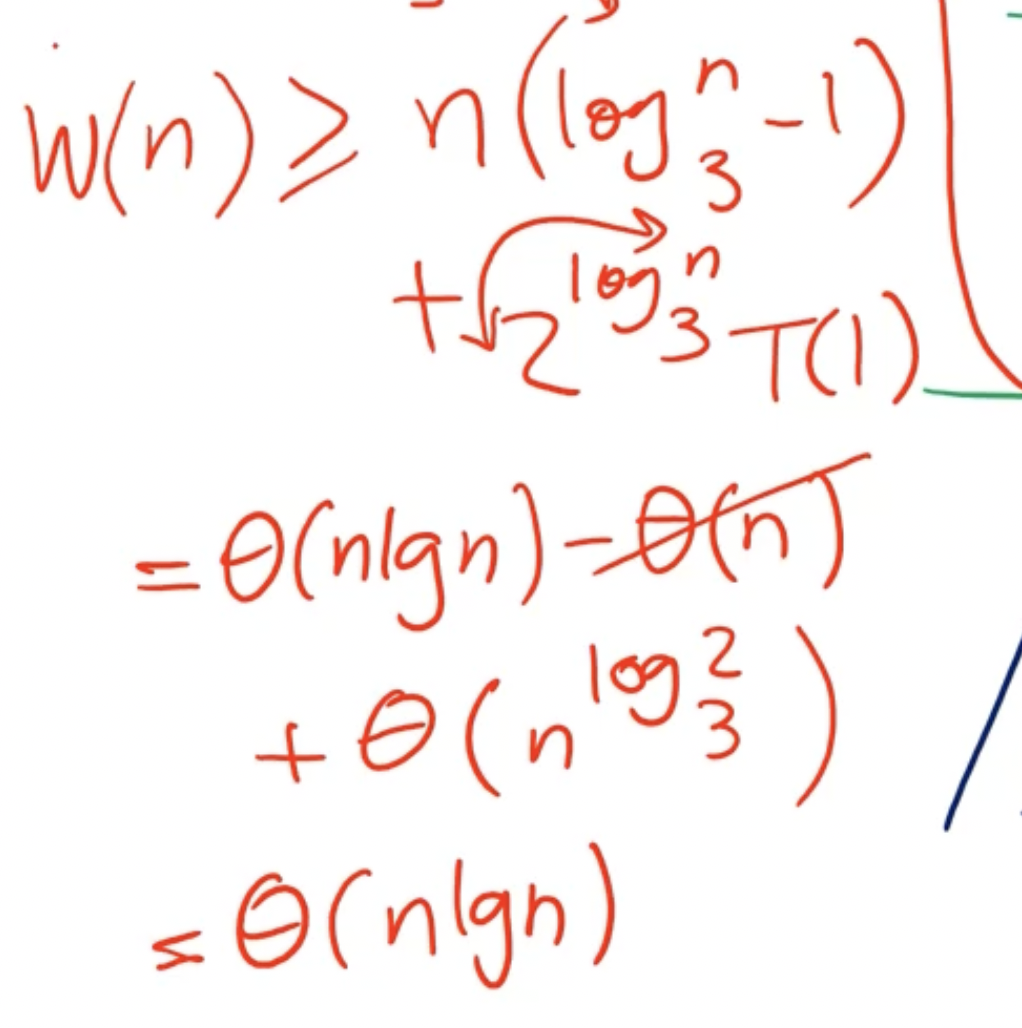

If we find the lower bound and upper bound, and they are the same, then we can say we found the exact bound. So, the lower bound is

Now that we have found a lower bound, lets find the upper bound:

Note: In the term \( n^{\log_\frac{3}{2} 2} \) , since the base in the log is less than the number, it means that the overall value is \( > 1 \) , so the polynomial term dominates the linearithmic term.

Since our lower and upper bounds are not equivalent, we cannot say we have an exact bound (big theta).

We can get a better assumption but not overestimating as much. If we assume that each level costs the same all the way down, then NOT include the leaf node costs, This would give our upper bound as \( O(n \lg n) \) , which matches our lower bound. That means we have an overall complexity of \( \Theta(n \lg n) \) .

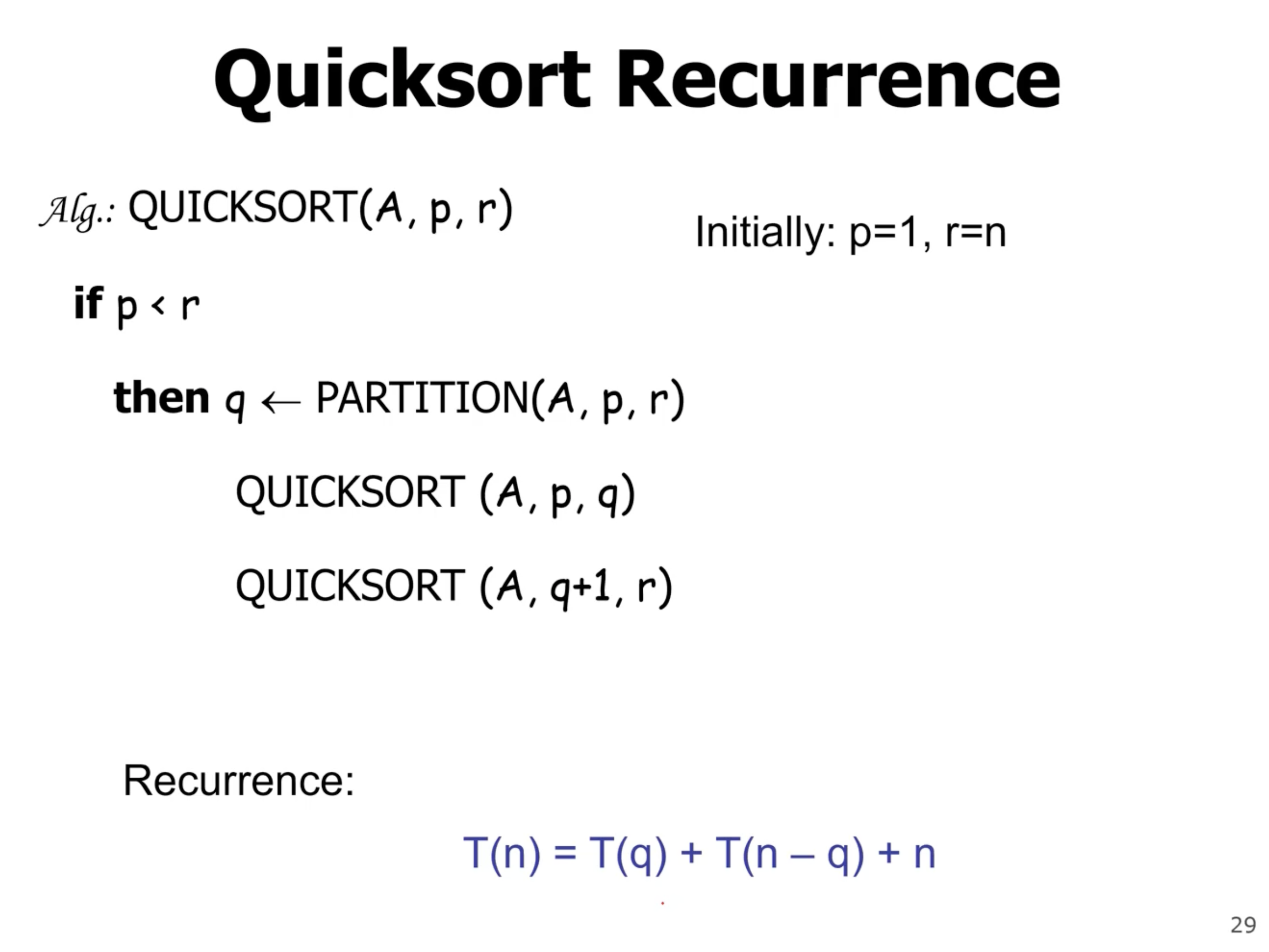

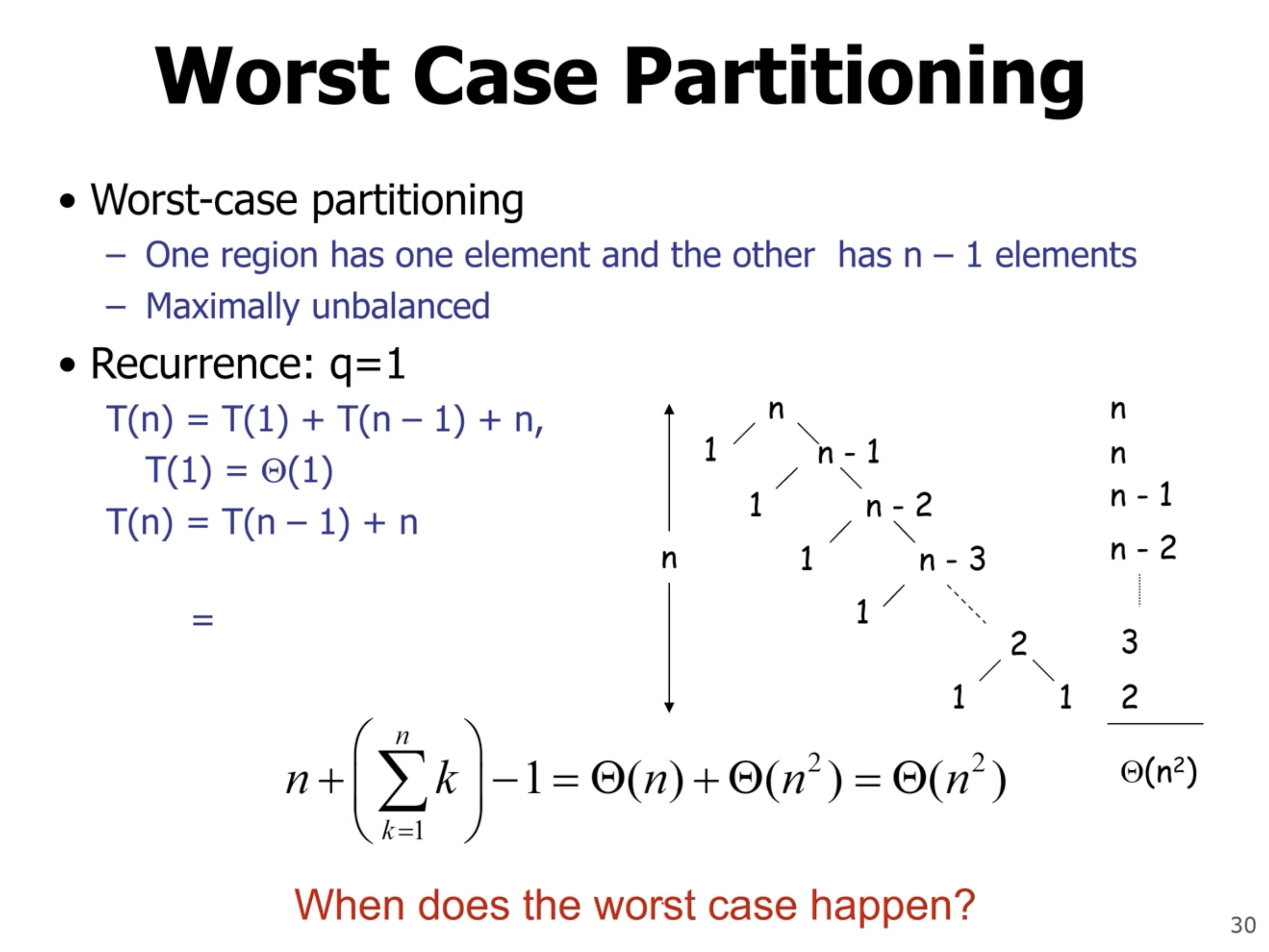

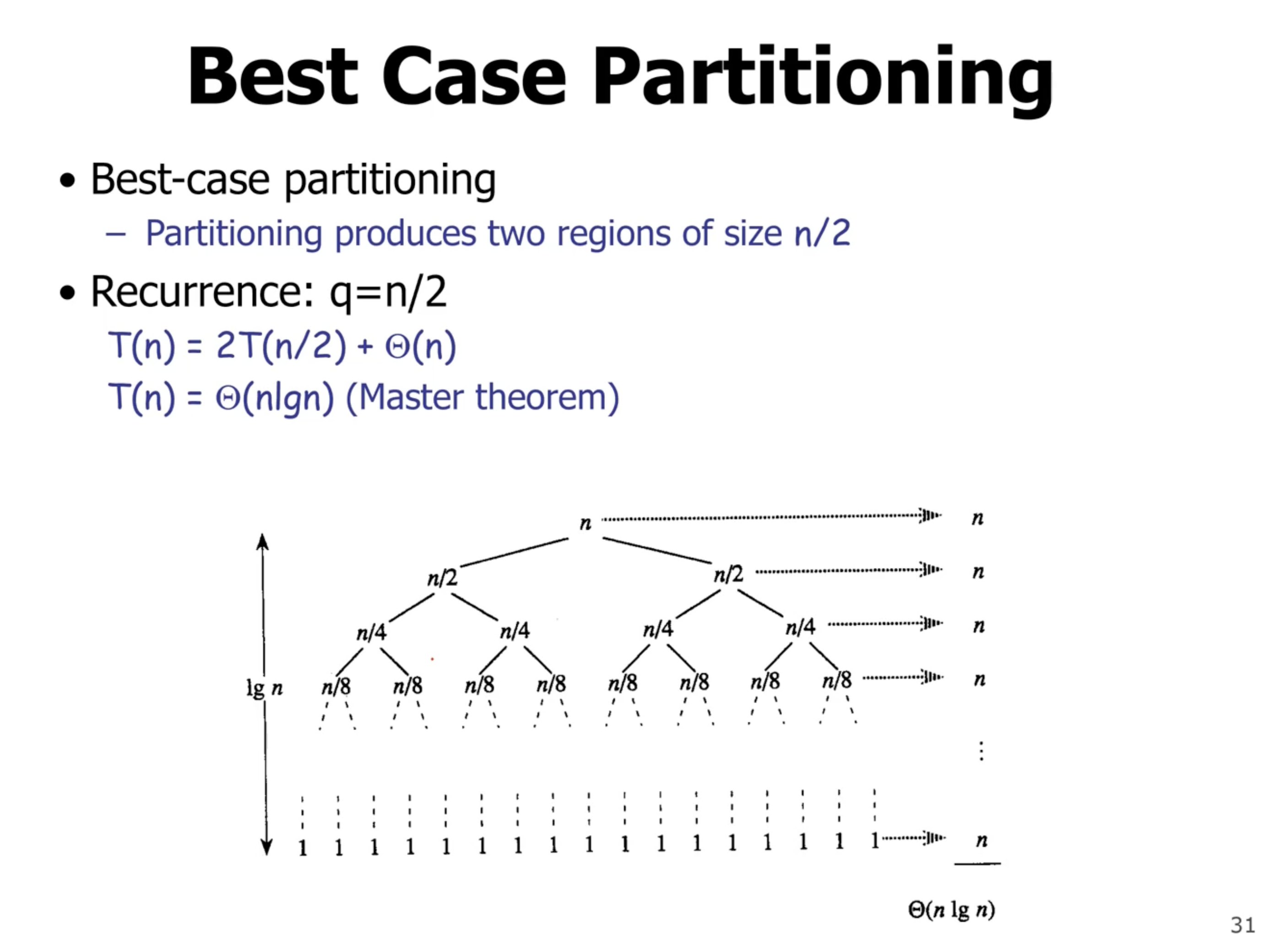

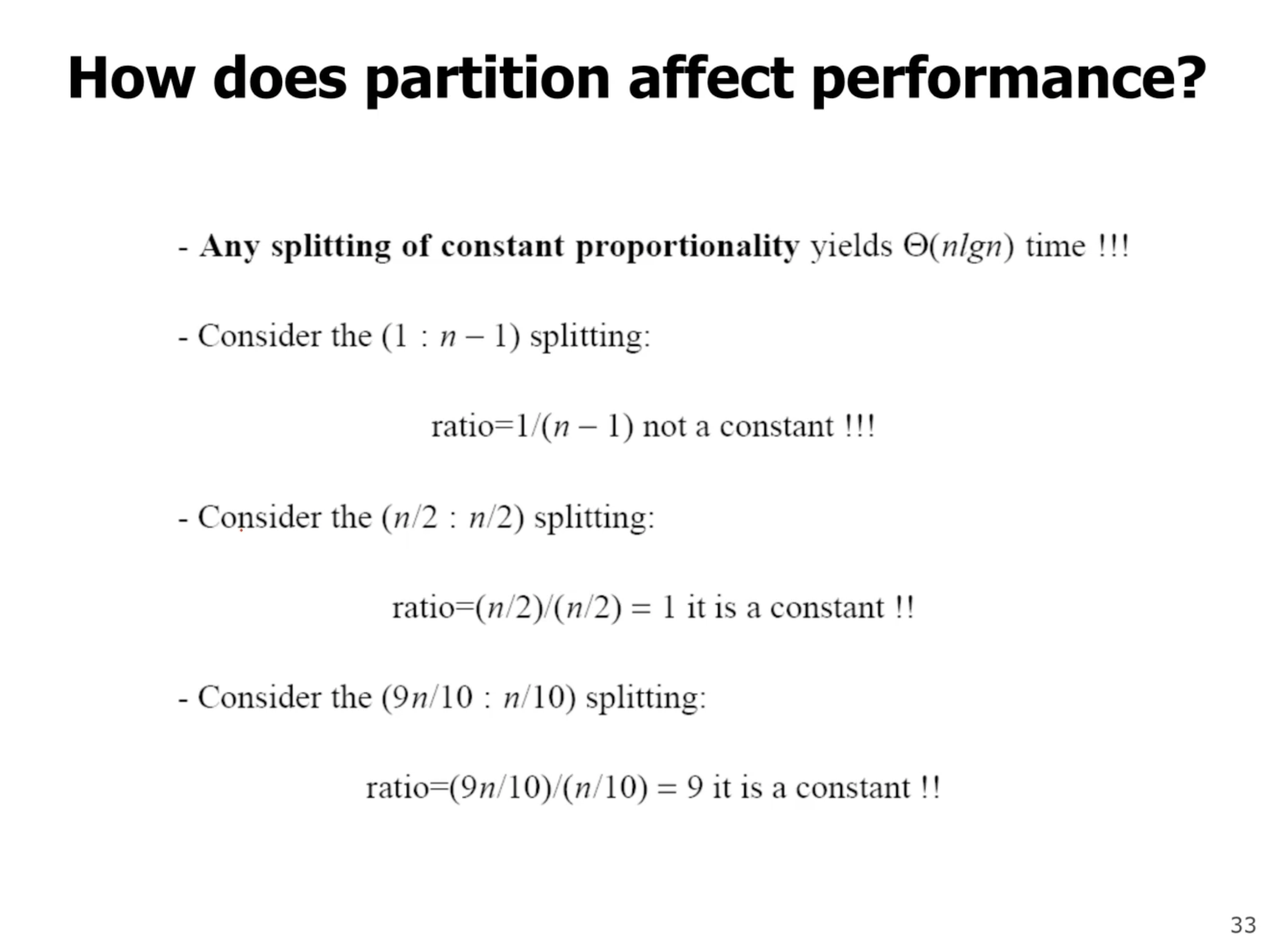

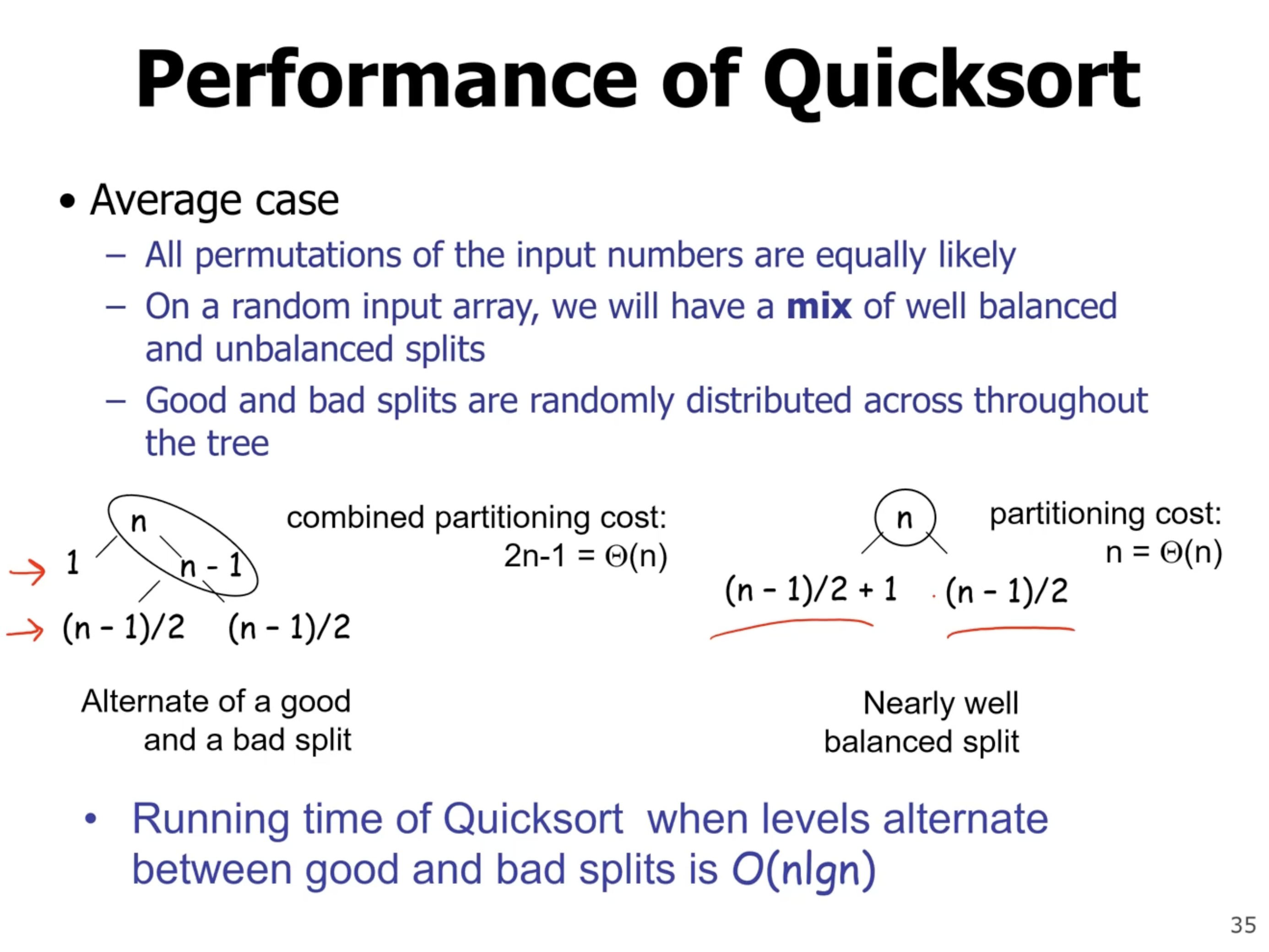

Quicksort recurrence #

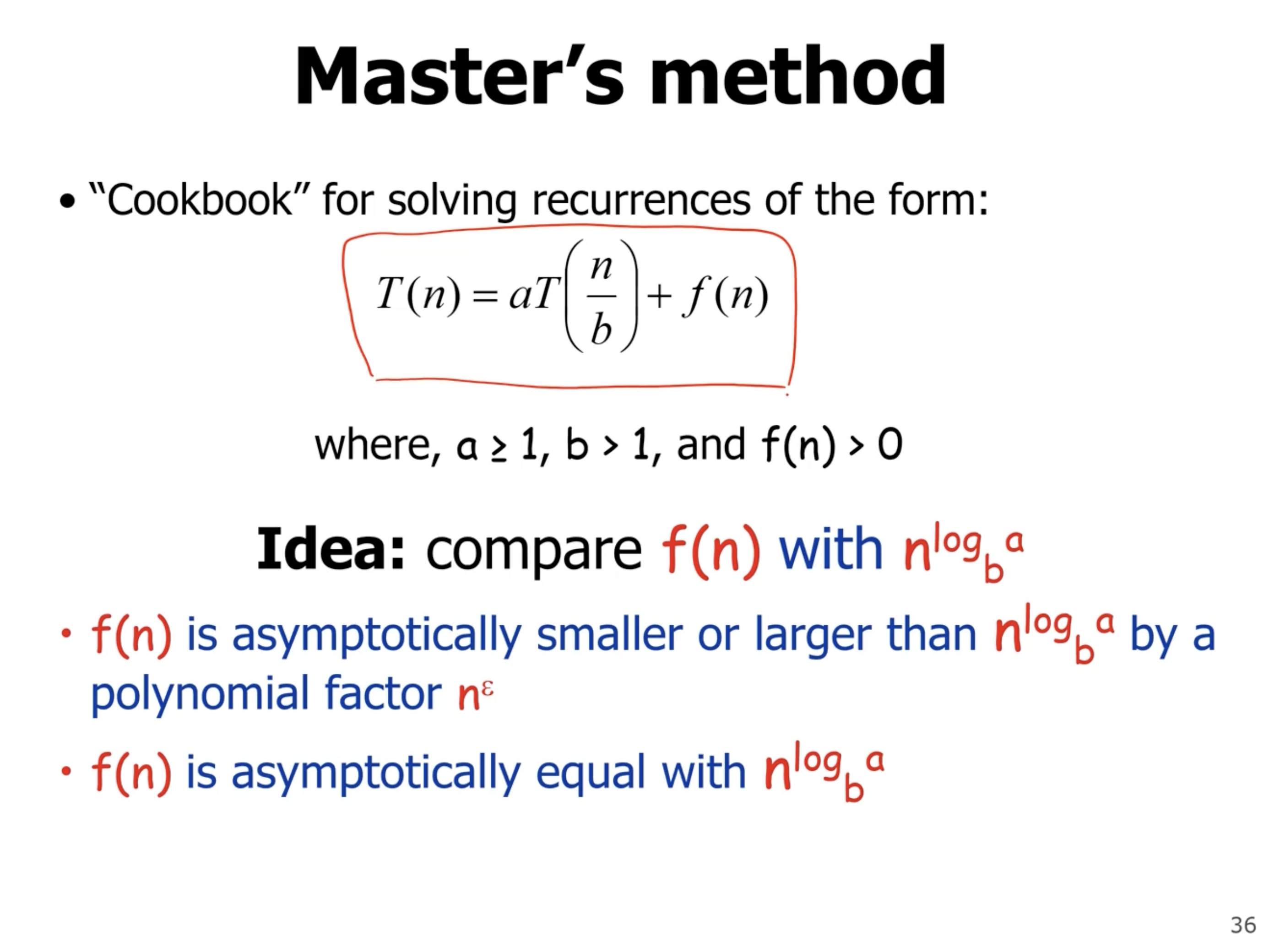

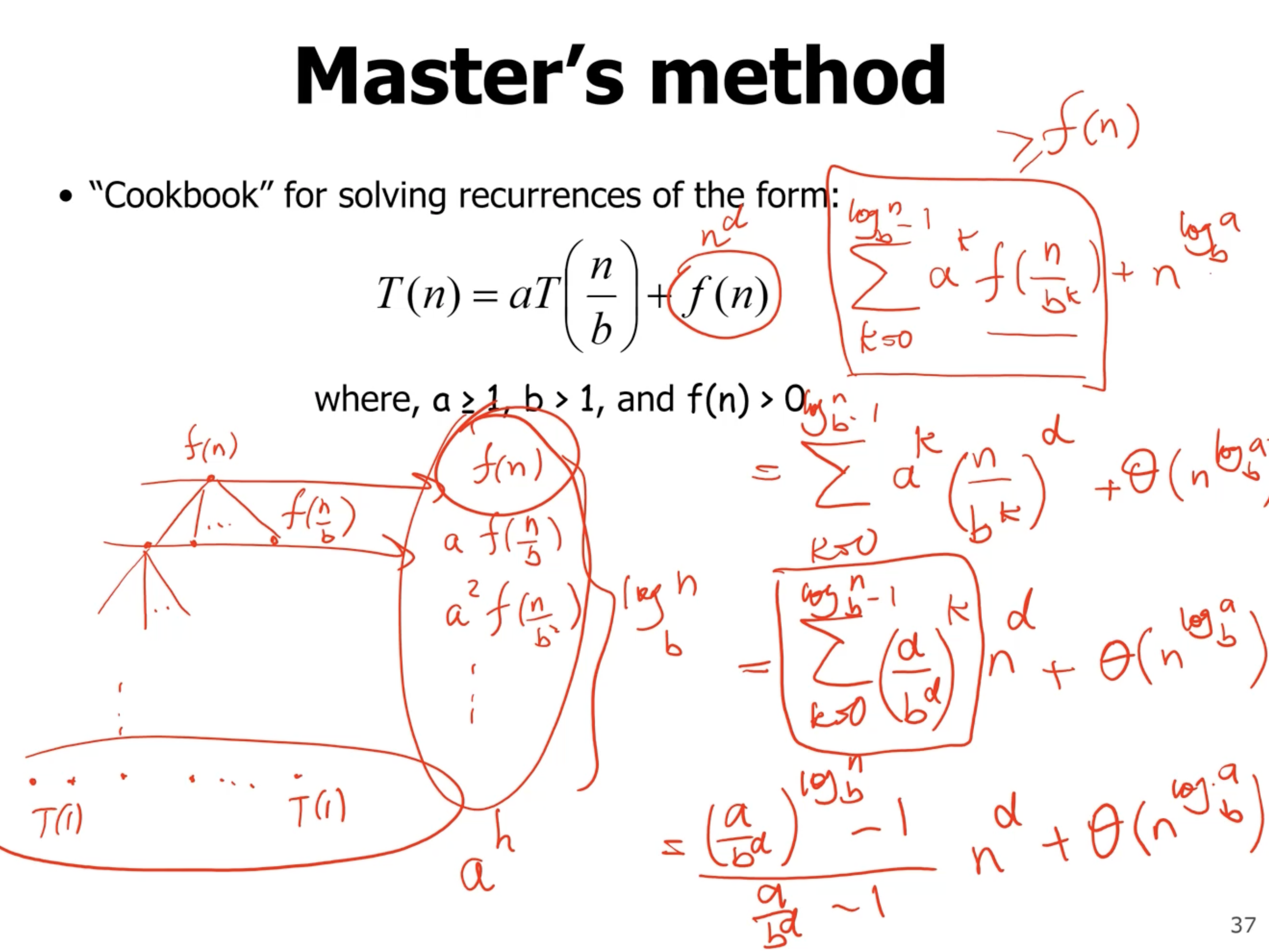

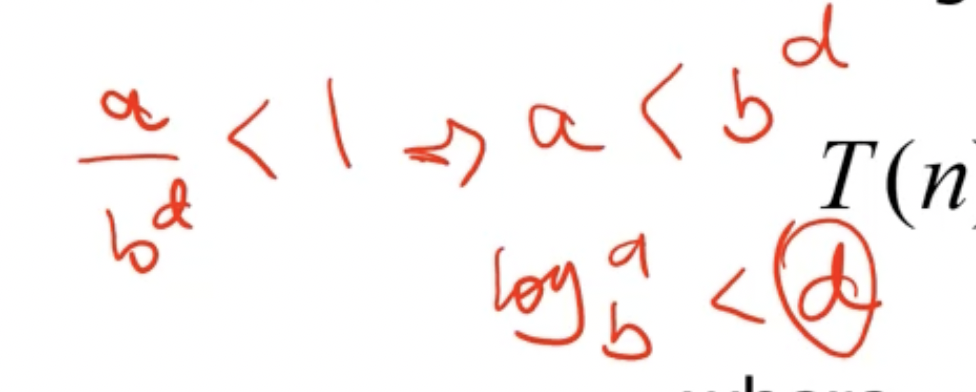

Master’s method #

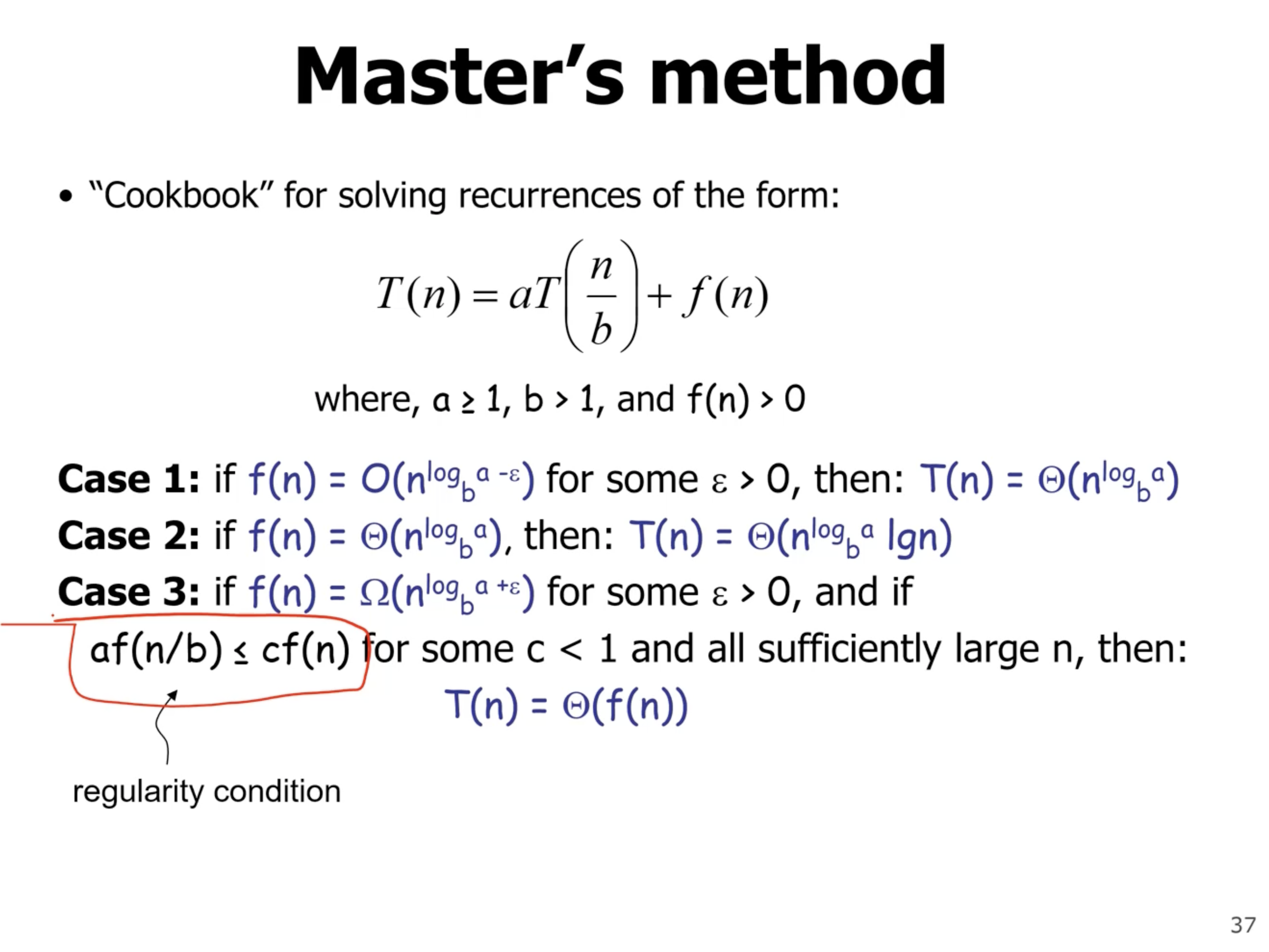

Masters method can be used when recurrences are in this exact form:

Generally, we’ll have 3 cases:

Lets visualize the first case with a recursion tree:

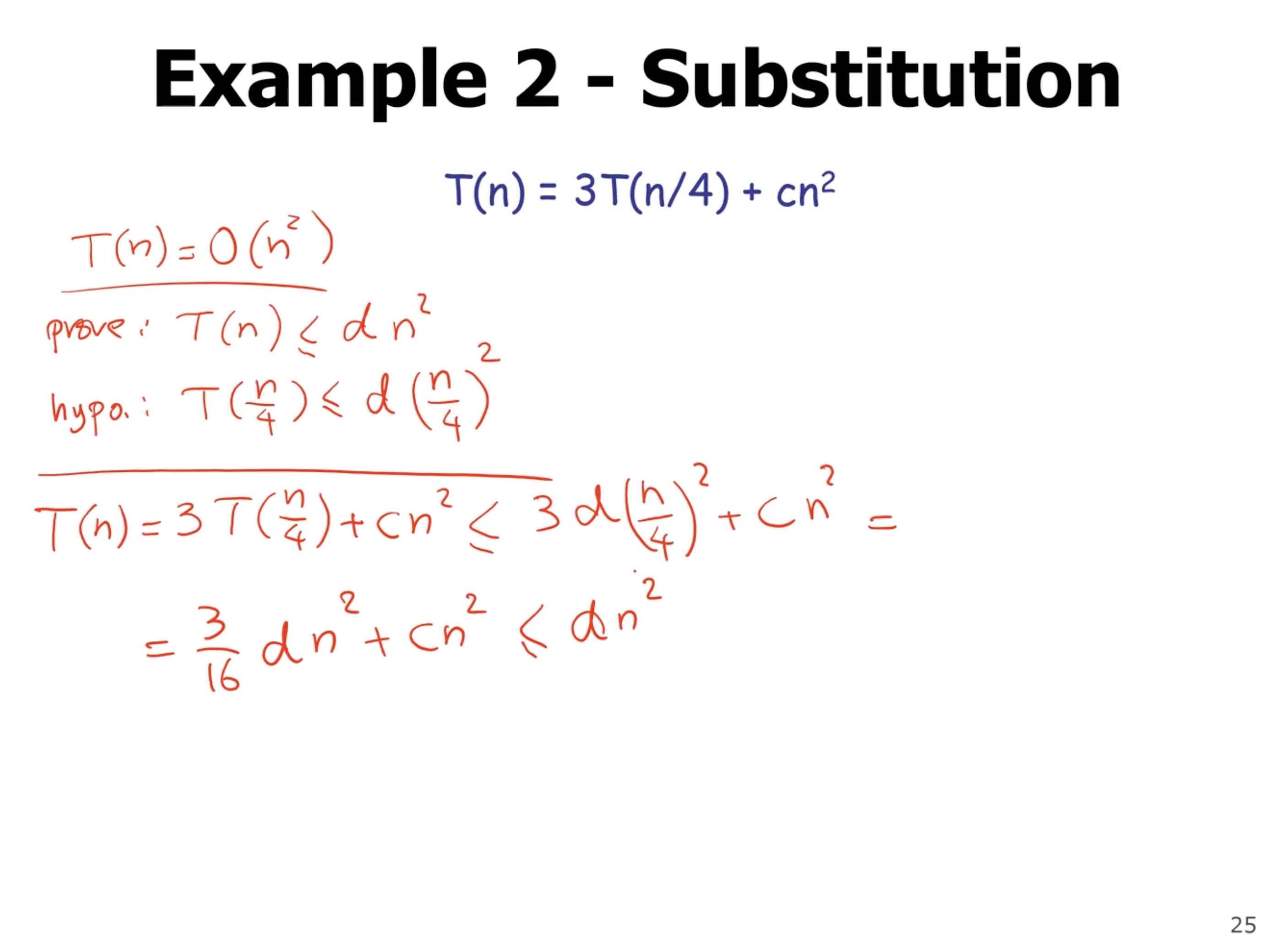

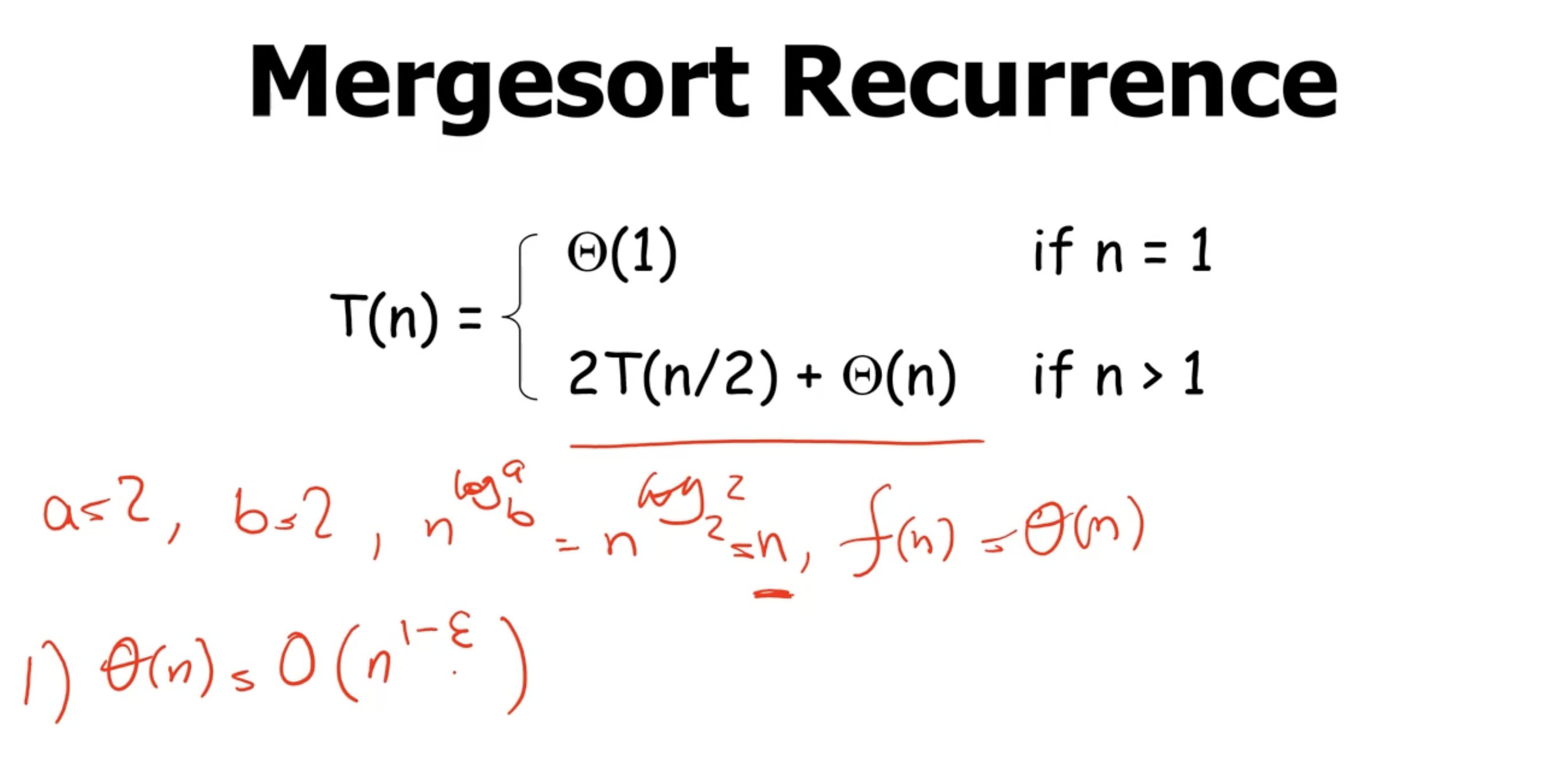

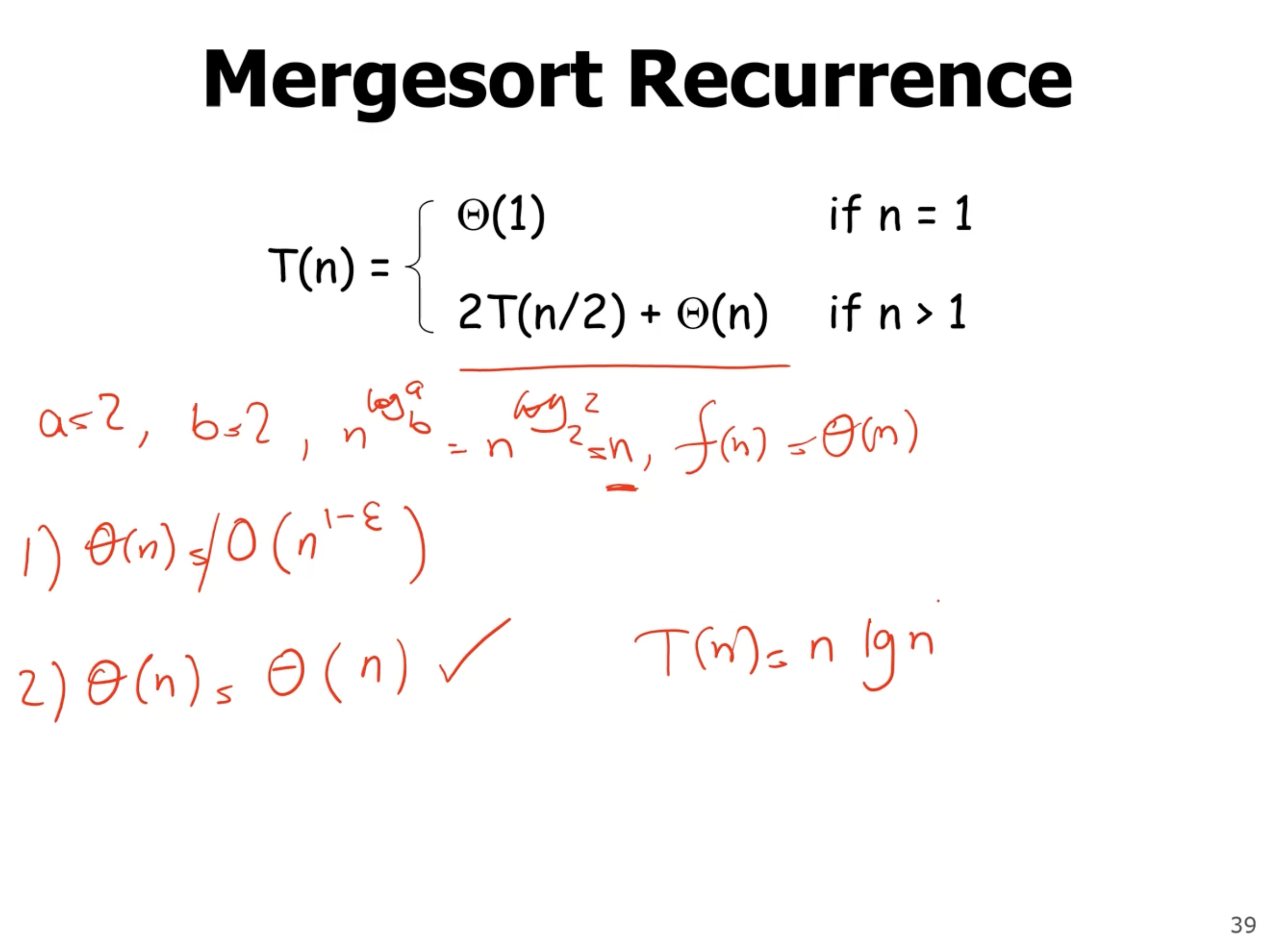

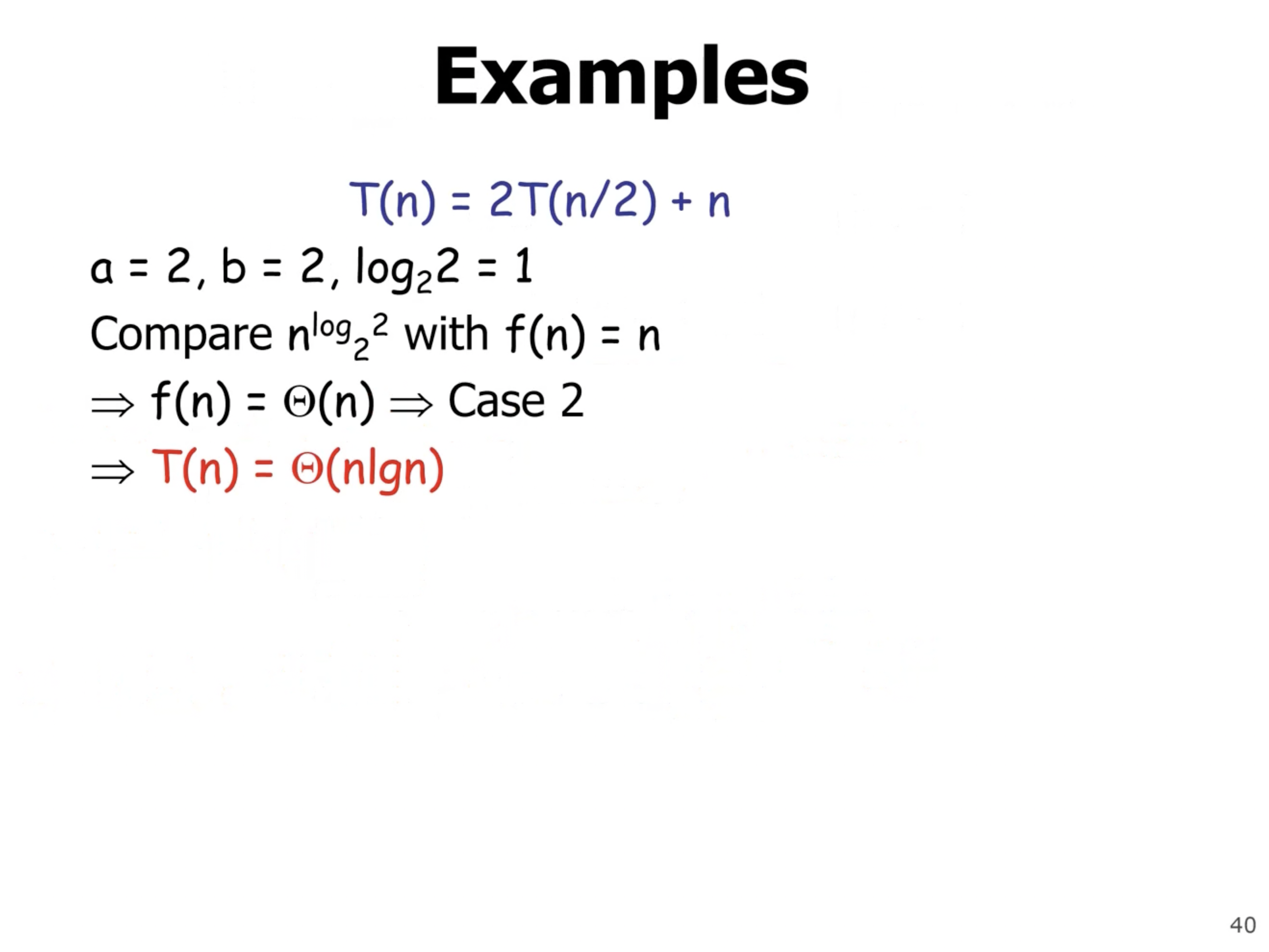

Mergesort recurrence using Master’s method #

So first we identify our variables \( a,b,f(n) \) and go thru the cases.

The first case is false because \( \Theta(n) \not = O(n^{1-\epsilon}) \) . So we check the second case, which is true because \( \Theta(n) = \Theta(n) \) .

So the Master’s method gives us a runtime complexity of \( \Theta(n \lg n) \) , which is the average case runtime of mergesort.

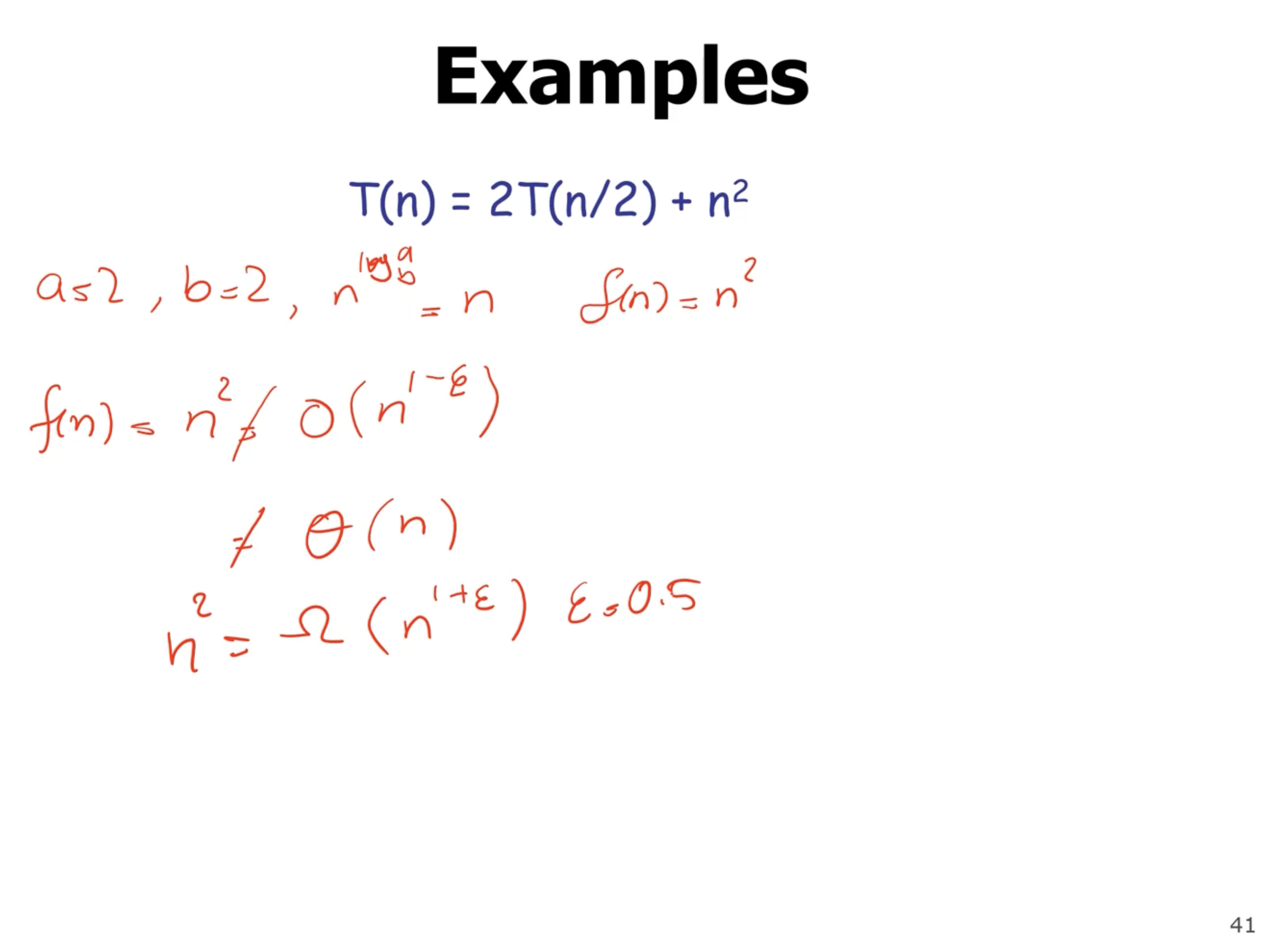

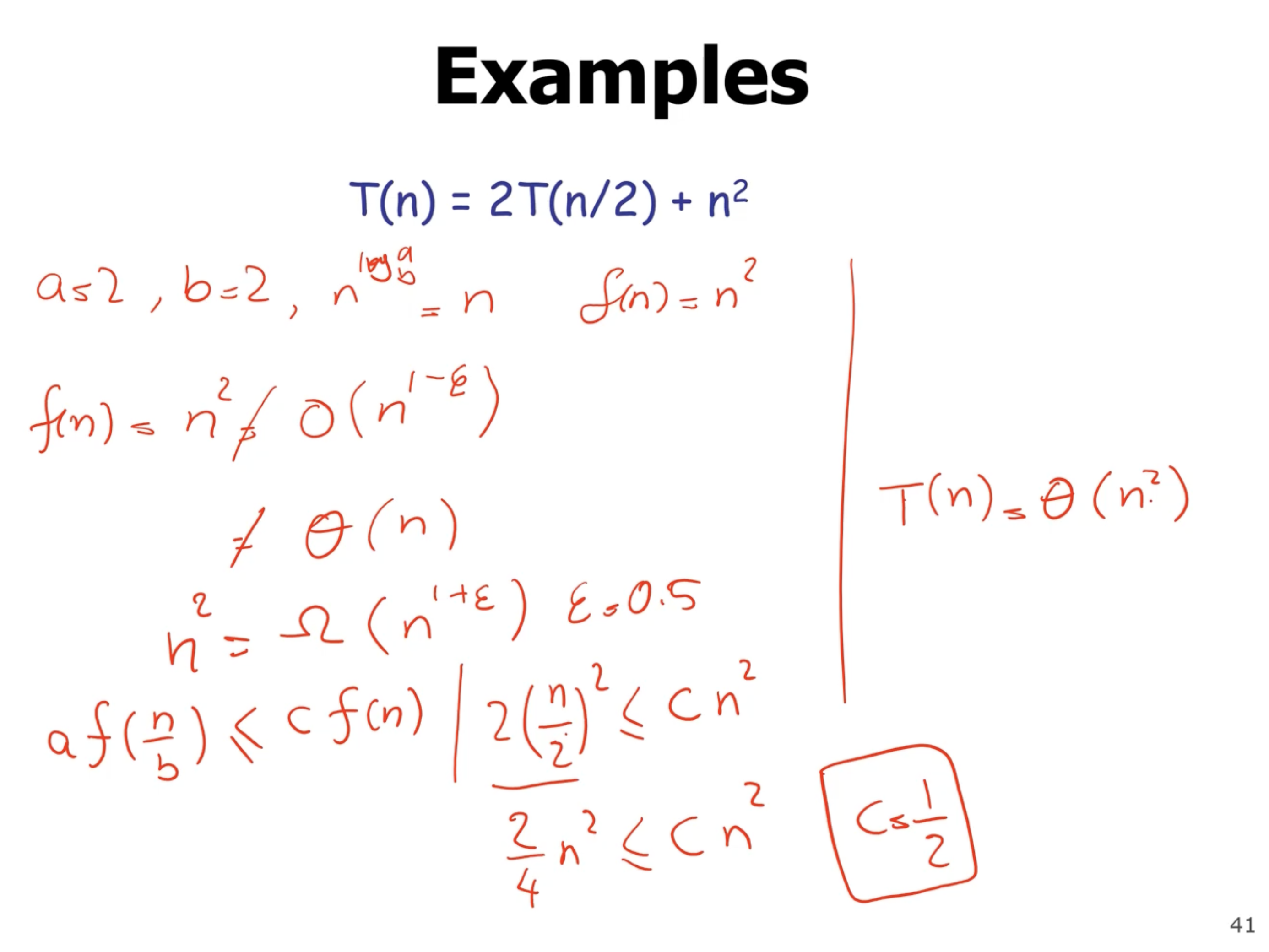

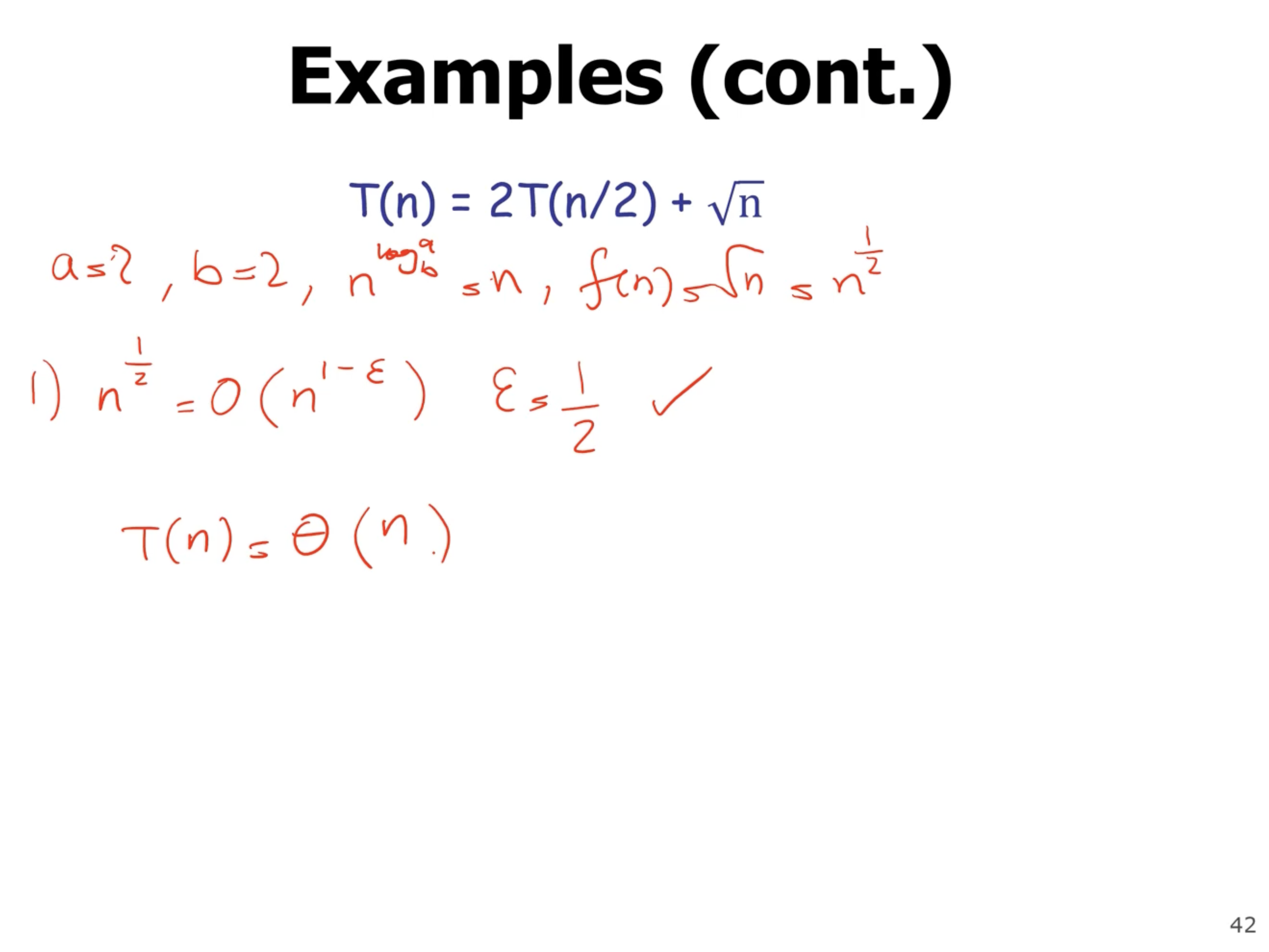

Some more recurrence examples using Master’s method #

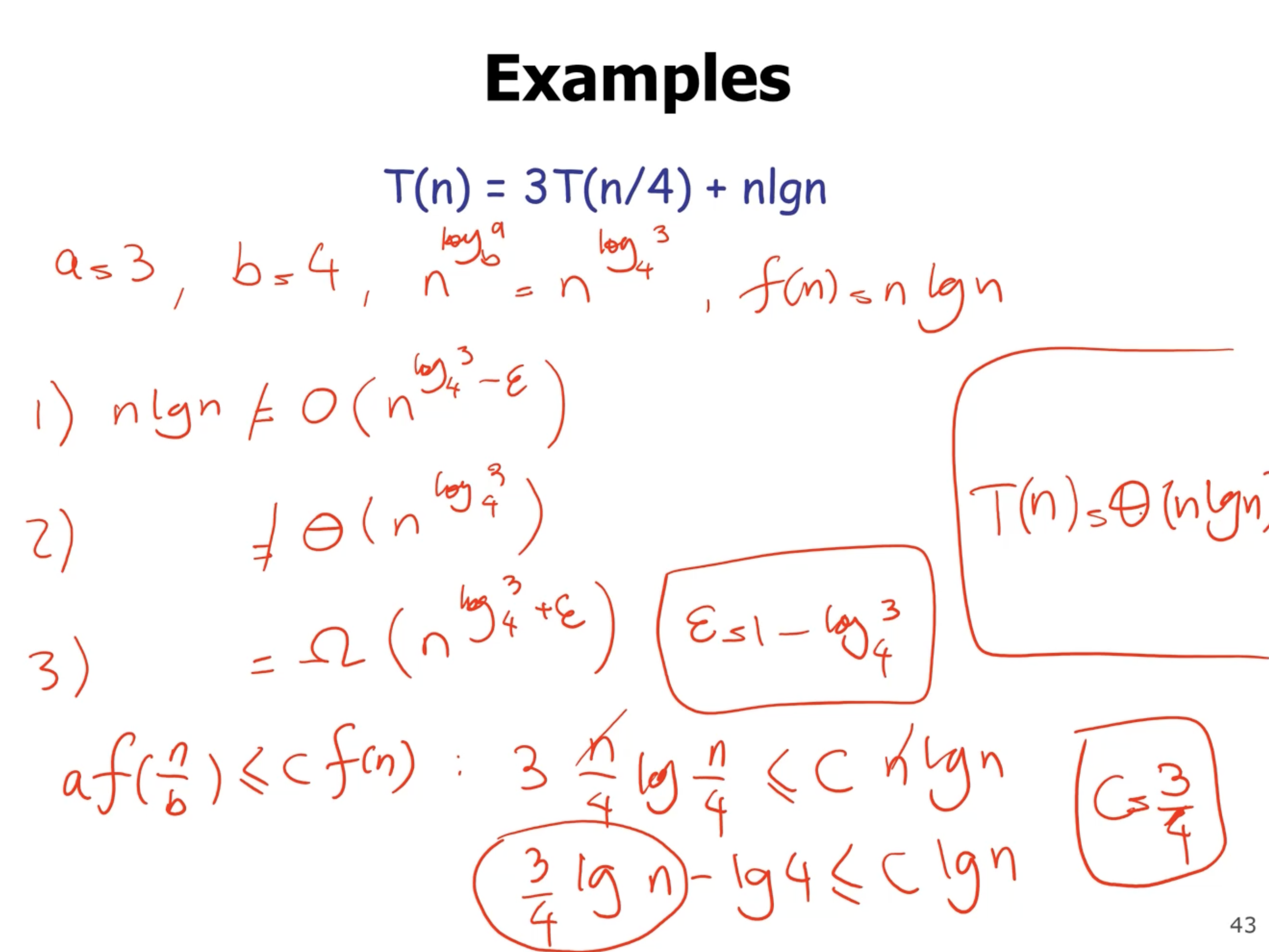

The third case works for this example, and you usually need to find a \( \epsilon \) value between 0 and 1.

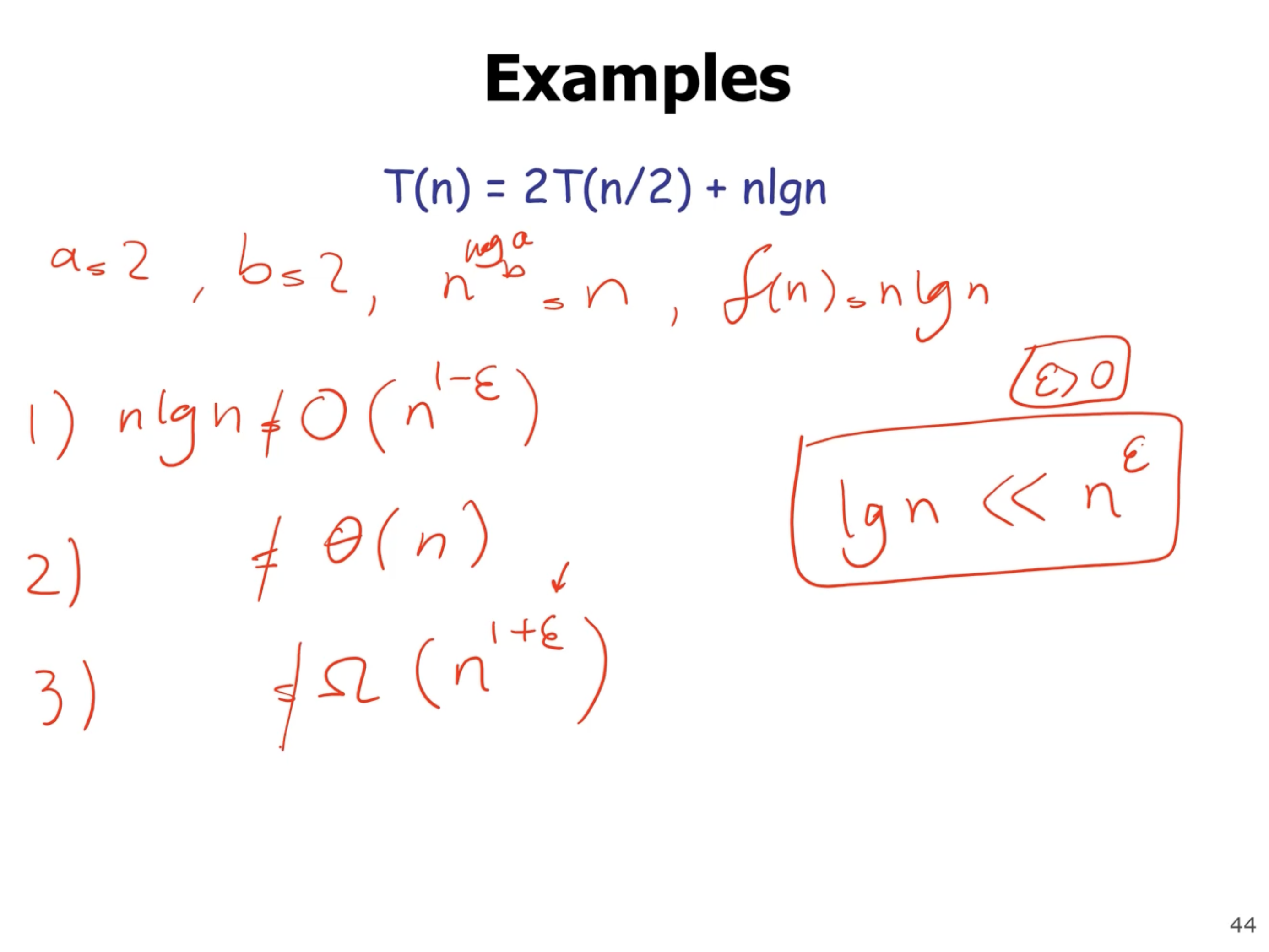

In this example, all 3 cases fail, so another method of solving recurrences it needed besides Master’s method.