Deadlocks cont. #

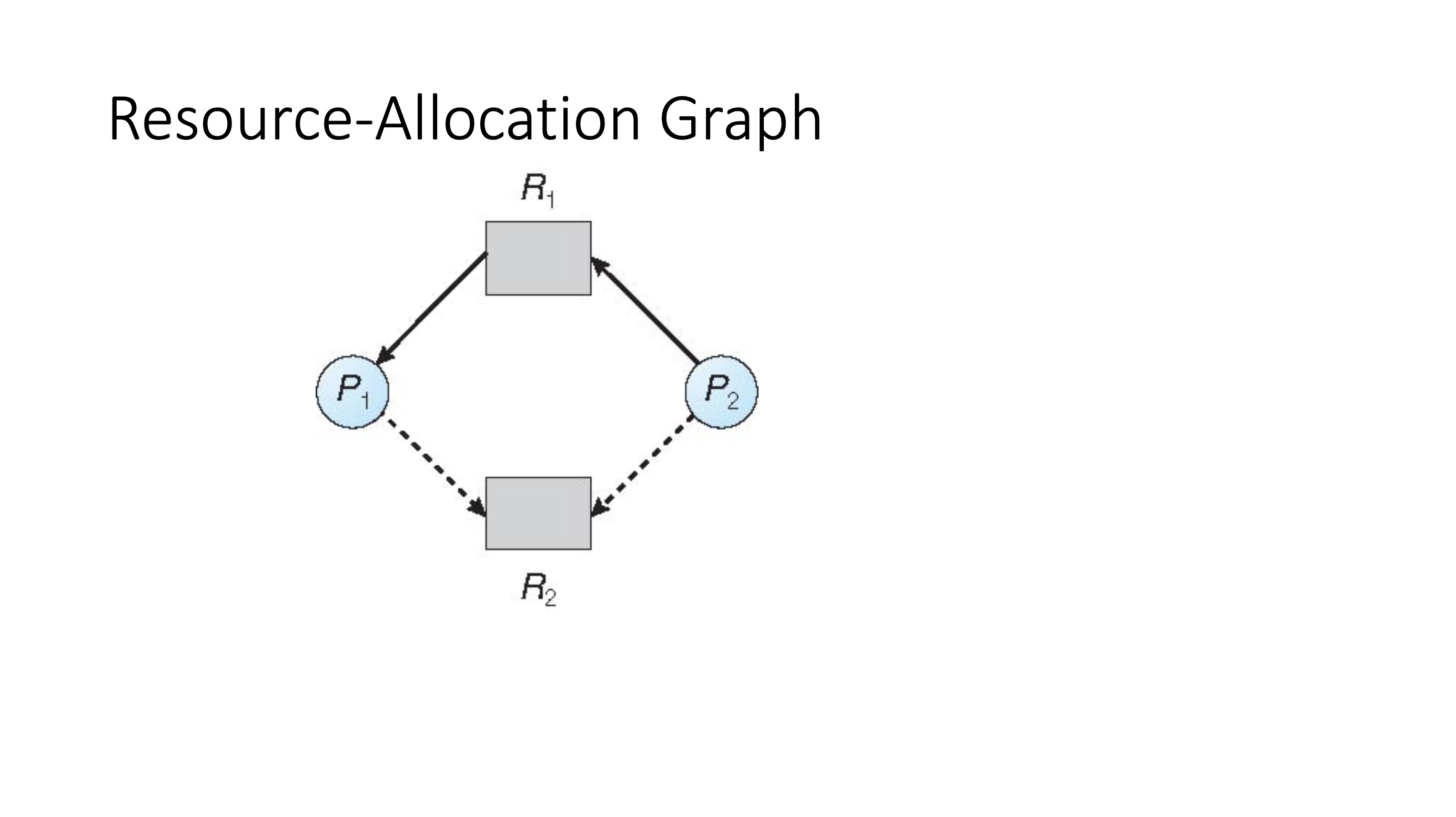

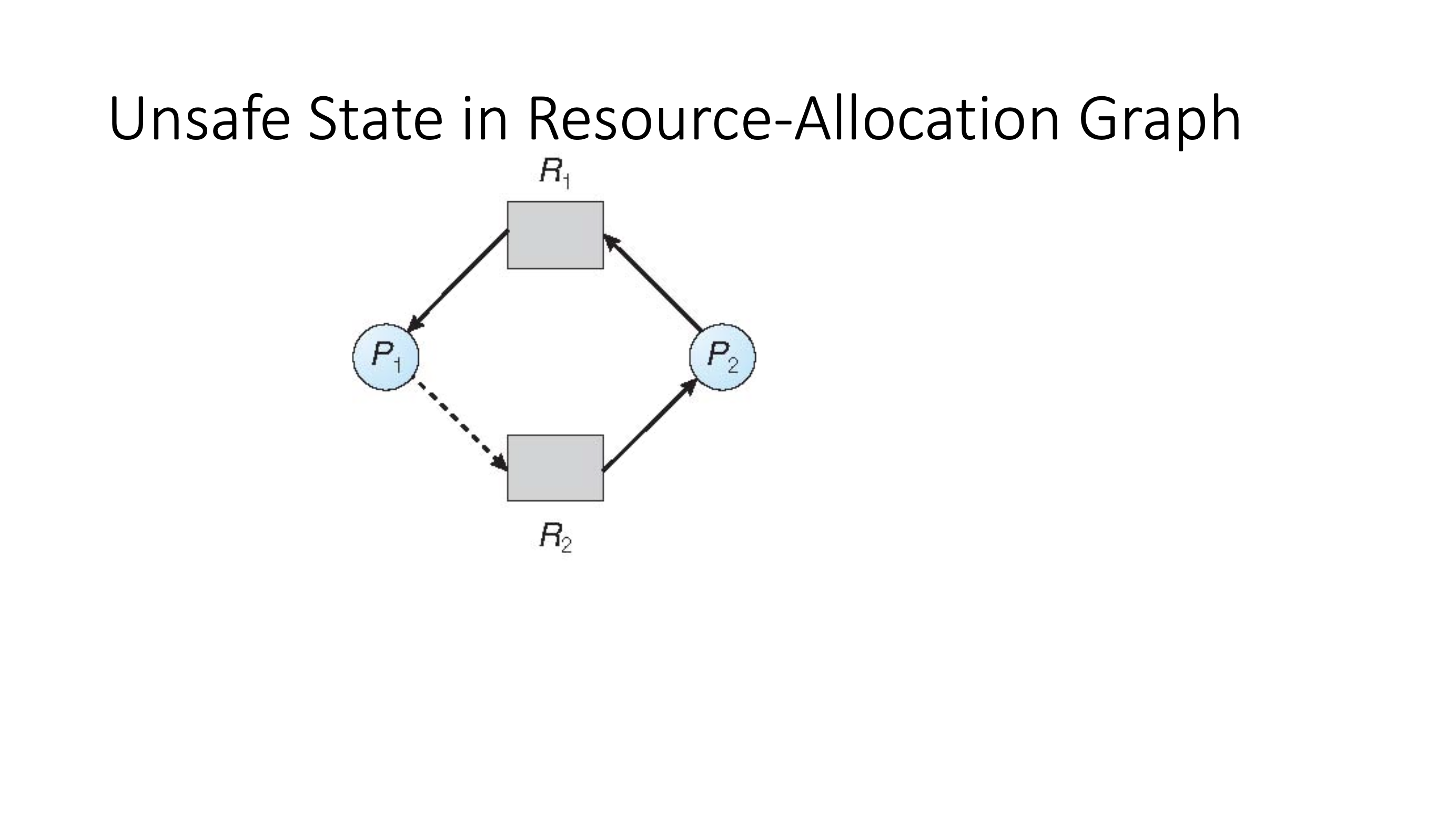

Resource allocation graph cont. #

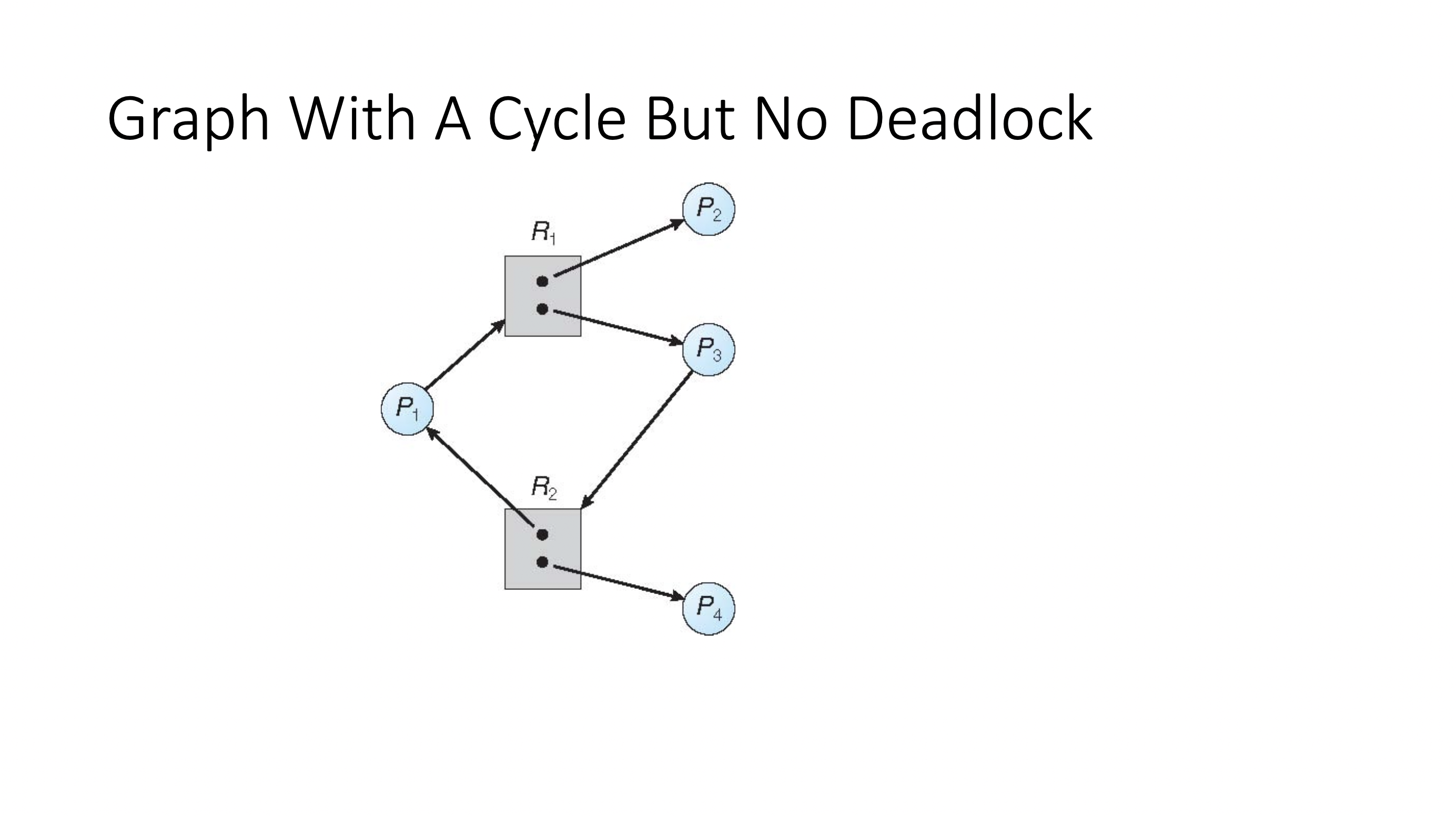

\( P_2 \) and \( P_4 \) have the ability to exit, so the resources they hold will be allocated elsewhere. No deadlock.

We can use a depth first search to look for cycles, to detect the possibility of deadlock.

Methods for handling deadlocks #

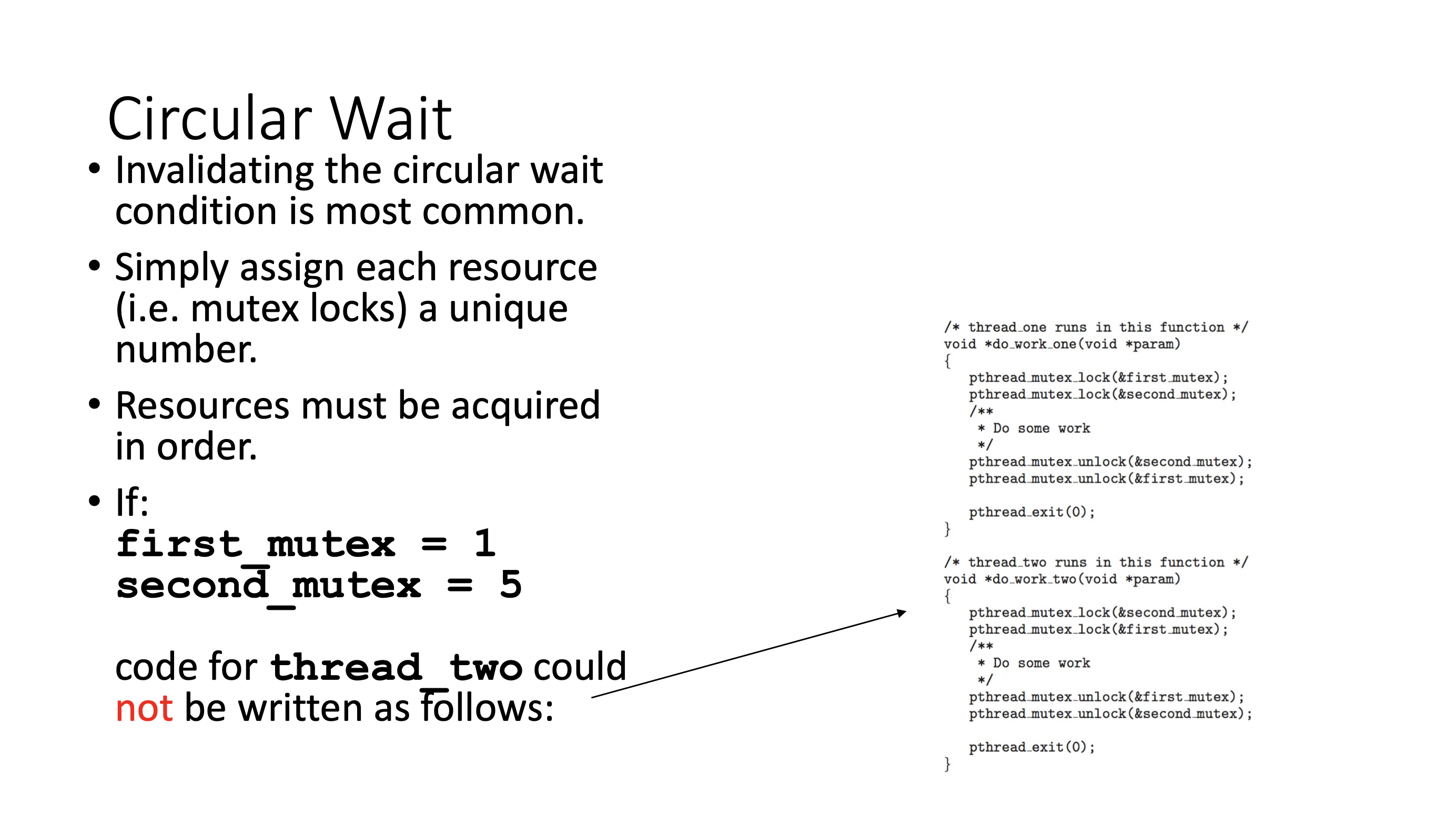

- to impose total order: if we have multiple resources, force process requests for resources in an increasing order of enumeration

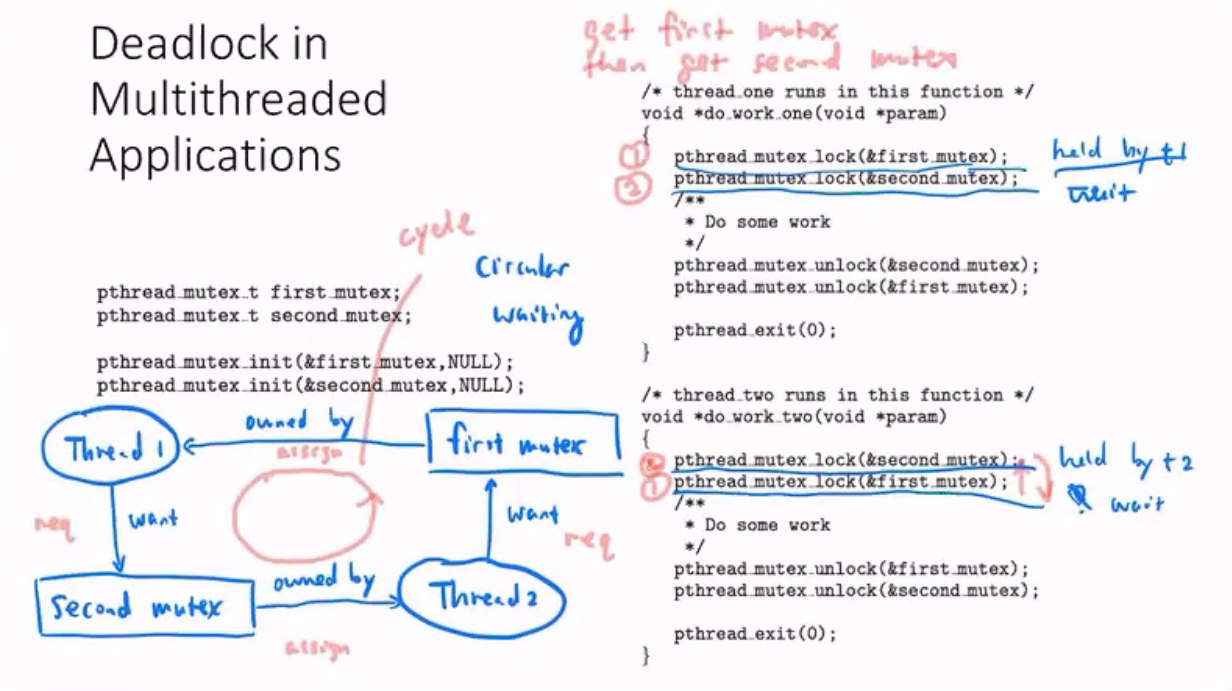

So, from the example before, if we swap the order in which each thread obtains lock (so they request the locks in the same order), we eliminate the deadlock:

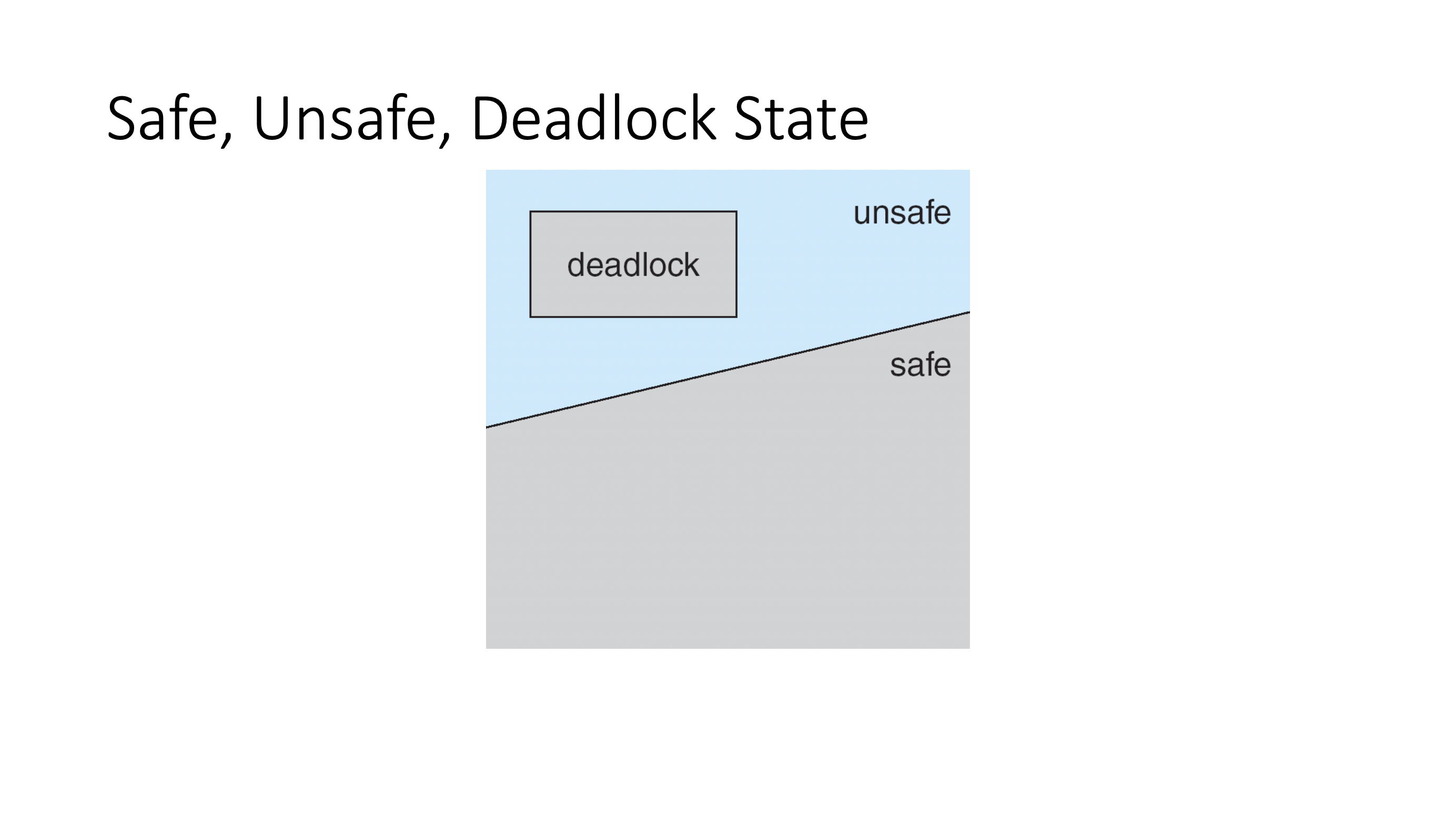

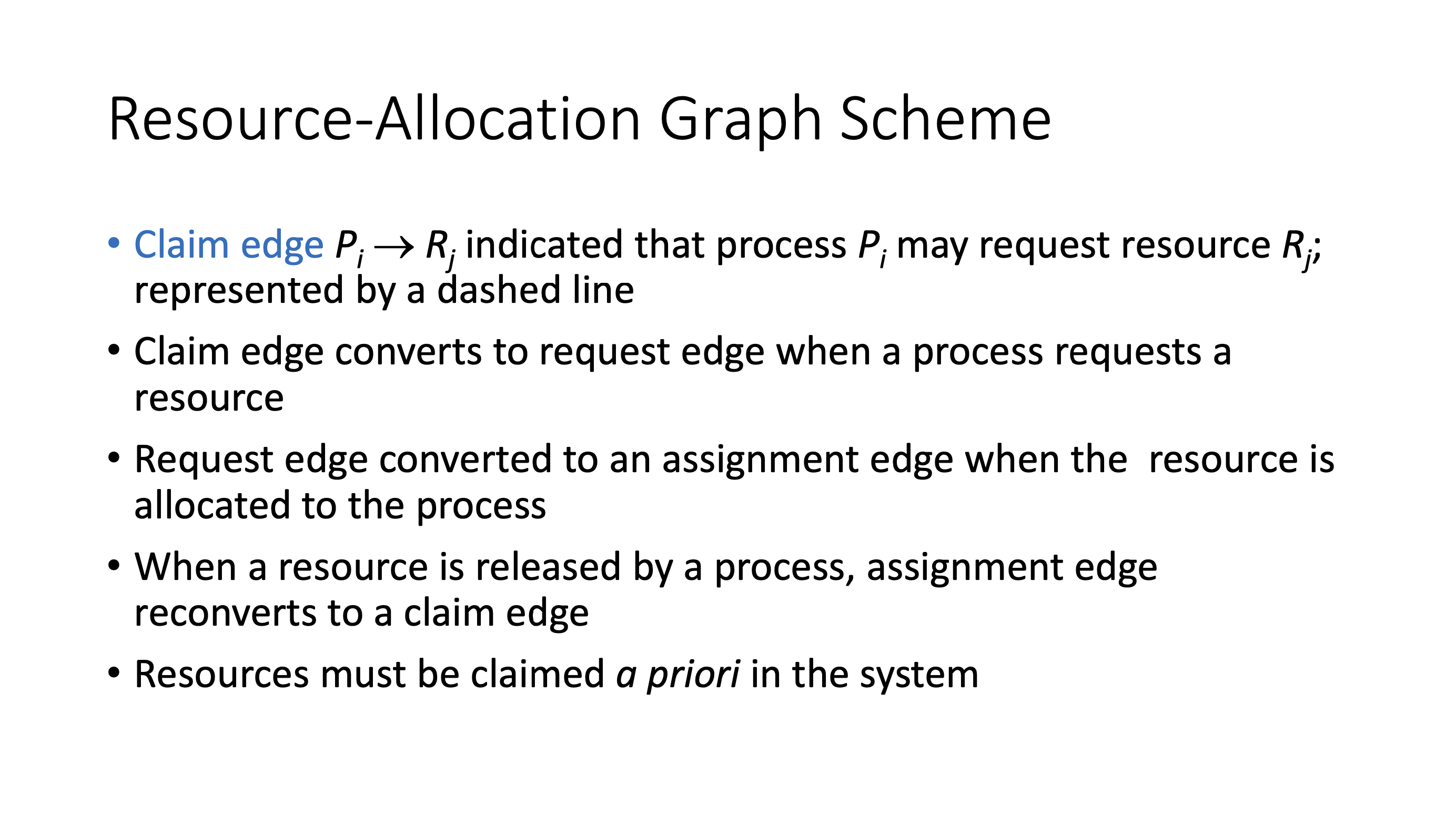

Deadlock avoidance #

- dotted lines indicate future requests, so we can detect cycles

Banker’s algorithm #

Another algorithm from Dijkstra. The banker’s algorithm can be used where there are multiple instances of a resource type.

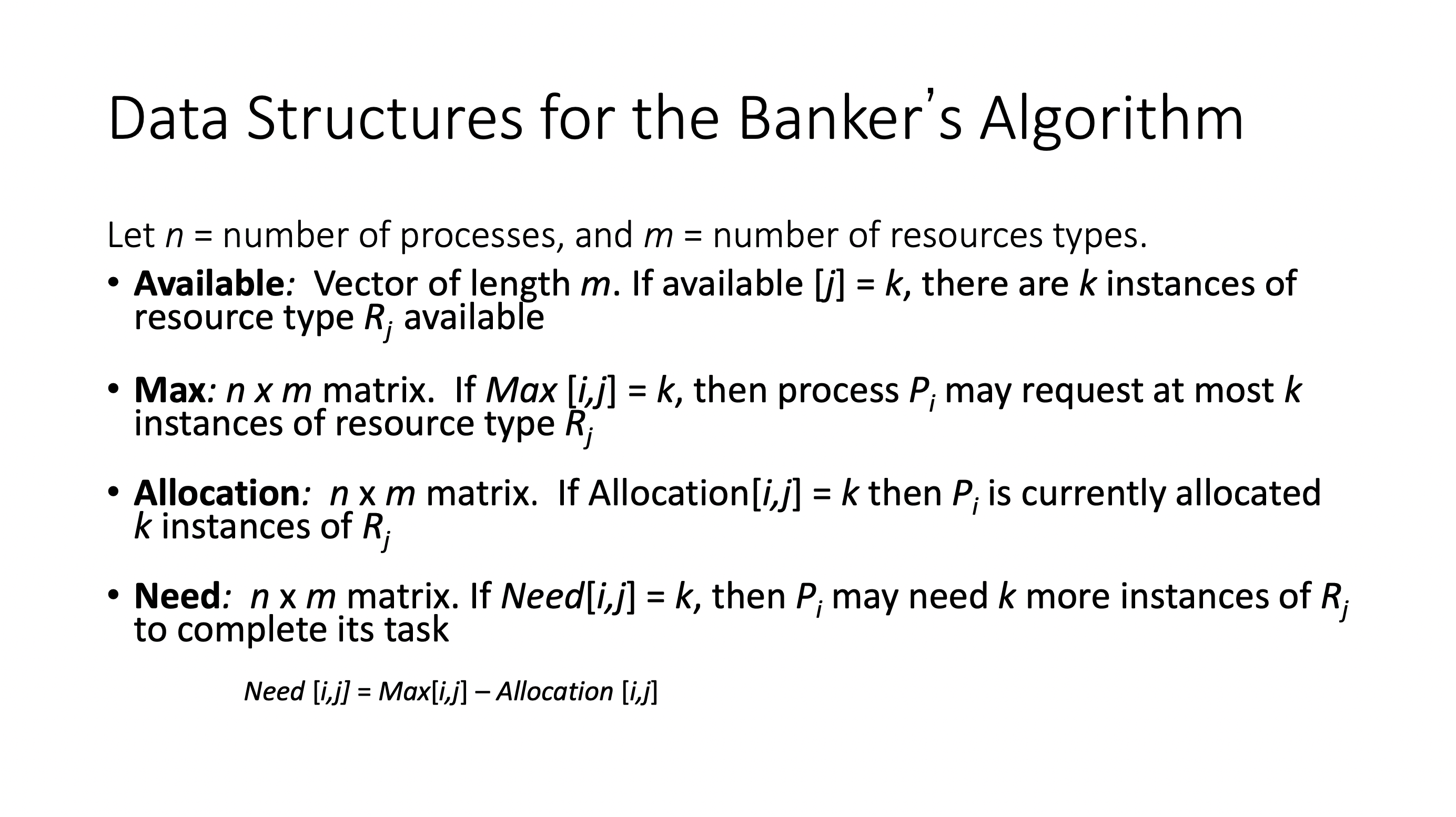

availableis the resource pool, the unallocated resourcesmaxis a matrix that stores the maximum use of each process, a quota for each process (the most resources a process may request)allocatedis a matrix that stores the currently allocated resources to their respective processneedis a matrix that stores how many more resources a process may request in the future

Total resources can be obtained by adding allocated + available.

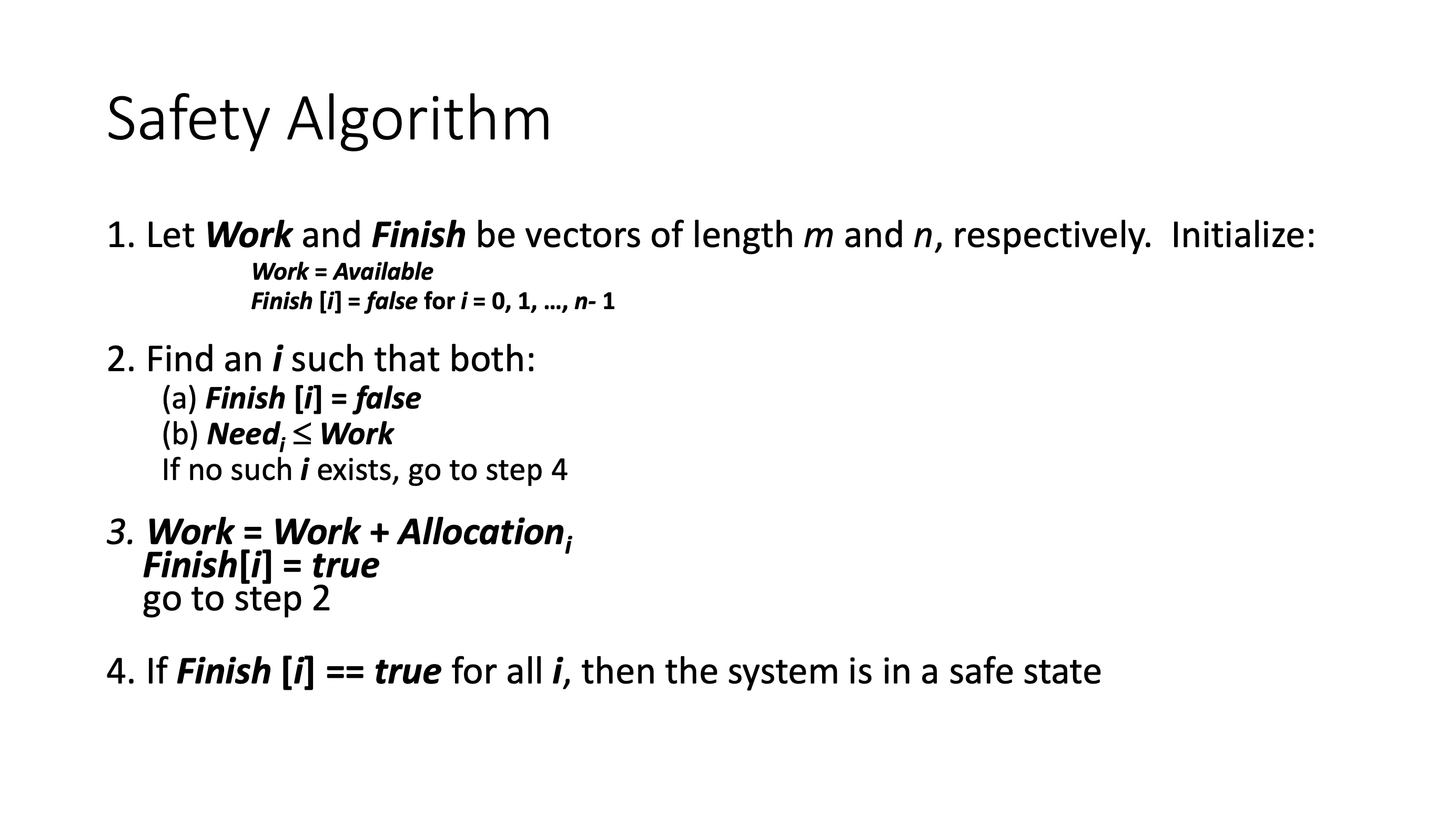

The first subroutine in the banker’s algorithm is the safety algorithm:

- returns whether the current state is safe or not

- step 3 basically simulates that the process completes